It happened on a perfect day for flying, in calm winds and clear skies, on a hot California morning.

It happened despite the five aviators involved having a combined total of 40,775 hours’ flying experience.

It happened seemingly against all normal odds.

“As a rule, even if you tried to ram an aeroplane in the air with another plane, you couldn’t do it,” insisted a flyer with close links to some of those involved.

And yet, 40 years ago this week, on Monday 25 September 1978 in one of the worst aviation disasters in history, Pacific Southwest Airlines (PSA) Flight 182 collided with Cessna Skyhawk N7711G 2,600ft over the American city of San Diego.

Instead of landing safely at San Diego International Airport as planned, Flight 182 smashed into the streets of the city itself.

A total of 144 people died.

In the Cessna, Martin Kazy Jr and David Boswell died as their light aircraft exploded on impact with the Boeing 727’s right wing.

Trailing flames and smoke from its wing, still carrying 128 passengers and seven crew, Flight 182 slammed into the ground at 300mph. All 135 people on board died. Only four of their bodies were found intact.

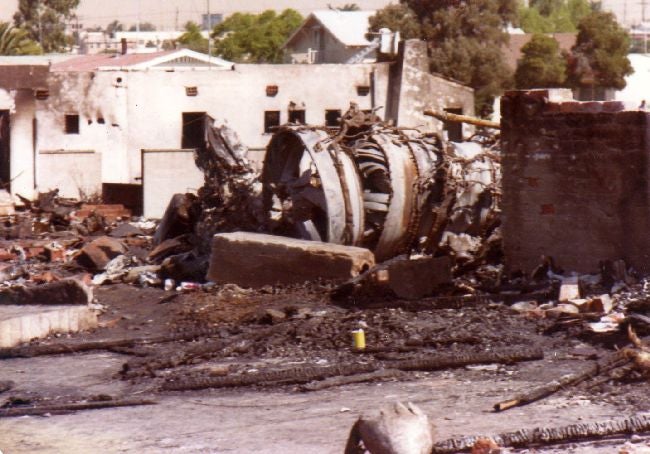

On the ground, first responders were confronted with scenes worthy of the Apocalypse.

“All around us was the stench of kerosene and burning flesh,” recalled Gary Jaus, who at the time was still in training at San Diego Police Academy. “There were no faces on the bodies. There were no bodies to speak of—only pieces.”

The 150,000lbs jet had hit the ground near the junction of Dwight and Nile Street, in the working class neighbourhood of North Park.

Jaus, who went on to become a sergeant in charge of community policing, told Thomas Shess of San Diego Magazine: “One alley was filled with just arms, legs and feet. I worked at Clairemont Mortuary before I became a cop - I was no stranger to dead bodies, but I wasn’t ready to see the torso of a stewardess slammed against a car.”

Other bodies – or body parts – landed on rooftops and in trees.

A total of 22 houses were damaged or destroyed, some consumed by fire, others crushed like matchsticks.

The jet’s impact claimed the lives of seven people who had been on the ground at the time.

One elderly woman had been talking to her sister when some of the blazing Boeing 727 smashed into her house.

“I saw them [first responders] pull the door up,” recalled Jaus. “Underneath were the remains of a victim. They guessed it was a woman, but they couldn’t tell.

“They guessed it was a resident instead of a passenger because the corpse was holding on to the receiver of a phone.”

At her home on the corner of Nile and Dwight streets, Nancy Stout, three days short of her 32nd birthday, had been in the process of saying goodbye to Cheryl ‘Sherry’ Walker, who was dropping off her son Derek, three.

Nancy was going to babysit Derek while also looking after four-year-old Robert, her son by her first marriage.

It almost never happened.

Nancy had been due to attend a court appointment that morning, about the plan for her new husband Harold to formally adopt her six-year-old daughter Candice. The appointment, however, was cancelled.

So while Harold went to his work as a Navy aviation electrician and Candice left for school, Nancy stayed at home with Robert and welcomed Sherry and Derek.

The two mums and the two little boys all died.

Twenty years later, Beverly Allread, the Stout’s next-door neighbour, told the San Diego Union Tribune of Harold Stout’s reaction when he got back home to be confronted by clouds of smoke, wrecked buildings and swarms of ambulances.

“He kept asking, ‘Where’s my family? Where’s my family?’

“And nobody wanted to even answer him.”

The death toll would have even worse had it not happened on a weekday morning when many people had gone to work or school.

But Darlene Watkins, a 29-year-old hairdresser still died. Monday was the only day of the week she took off.

The Flight 182 crash remains California’s worst ever aircraft disaster. It was, for a time, the deadliest plane crash in US aviation history.

It prompted a raft of air traffic control improvements.

It was also used in the teaching future air crash investigators, as an example of how human error can be a factor in aviation disasters.

How big a factor human error was, however, became a matter of some dispute.

By April 1979 the National Transportation Safety Board had pieced together the final moments of Flight 182 and Cessna N7711G to produce a detailed, but contested aircraft accident report.

For the Boeing 727, it began as a routine commuter flight on the cheap and cheerful airline where every jet, including Flight 182 had a great big smile painted on its nose cone.

The jet left Sacramento bound for San Diego International, then known as Lindbergh Field, via Los Angeles.

At LA, 102 lucky passengers got off the plane. But 100 people got on.

It should have been 101. E. Jack Ridout, returning to San Diego after a business trip in LA, had booked himself a ticket on Flight 182.

But Ridout had been staying with a friend whose air conditioning had broken in the middle of an LA heatwave.

Unable to stand the heat, he apologised to his friend and travelled home on the Sunday, a day earlier than planned.

In cancelling his Flight 182 ticket, Ridout cheated death in his second air disaster.

Eighteen months earlier he had been one of only 61 survivors when a Pan Am Flight 1736 and KLM Flight 4805 collided on the runway at Tenerife airport, killing 583 people in the deadliest accident in aviation history.

Before that, injuries sustained in a car accident had saved him from being enlisted for combat in Vietnam.

Among those who were on board Flight 182 were Azmi David Taha, a 16-year-old high school pupil, Lee H. Thompson, a 36-year-old whose wife was pregnant, and Pauline “Pam” Colarich, 23, flying from her Sacramento home to start her career as an archaeologist in San Diego. She would be one of the last to be identified, from dental records.

In the cockpit was Captain James E. McFeron, 14,382 hours flying experience, 10,482 of them on Boeing 727s, 17 years into his job with PSA.

“A born pilot,” they called him, a flyer who “always seemed two heartbeats ahead of the situation”.

The first officer, Robert Eugene Fox, with 10,049 hours experience, was looking forward to the training that would allow him to be upgraded to full captain.

McFeron and Fox were accompanied by flight engineer Martin J. Wahne, 44, who had been with PSA since 1967.

In the cockpit jumpseat, although only in an off-duty, observing capacity was Captain Spencer Nelson, a pilot with more than 28,000 flight hours under his belt.

By coincidence, prior to joining PSA in 1952 Nelson had been a student and flight instructor at Gibbs Flite Centre at Montgomery Field, about eight miles north of central San Diego.

It was from here that Cessna N7711G took off at 8.16am. On board the four-seater were Gibbs Flite Centre instructor Martin B Kazy Jr, 32, and his pupil David Boswell, 35.

Although the Cessna had dual controls, allowing Kazy to take over if necessary, Boswell, a gunnery sergeant in the US Marines, was himself a relatively experienced flyer, with a commercial pilot certificate and a total of 407 flight hours. Kazy was training him to fly by instruments only.

They headed to Lindbergh field, which at the time was the only airport in San Diego County with an instrument landing system (ILS), meaning even small aircraft used it for practice.

By the time Flight 182 was beginning its approach to Lindbergh Field, Kazy and Boswell had already done two practice ILS approaches to the runway.

As the jet approached, first officer Fox was at the controls, with Captain McFeron handling nearly all the air-ground communications.

Flight 182 would be guided by two separate air traffic control centres, beginning with San Diego Approach, which was also communicating with the Cessna, before Lindbergh Field Tower took over when the jet was 15 nautical miles from landing. All perfectly standard at the time, but, as the subsequent crash report noted, potentially confusing.

At 0900 and 15 seconds San Diego Approach advised Flight 182 of the Cessna’s presence with the words: “Traffic’s at 12 o’clock [straight ahead]”.

At 0900 and 21 seconds , first officer Fox said ‘Got ‘em”, and the next second Captain McFeron confirmed: “Traffic in sight”.

Flight 182 was advised by the approach controller to “maintain visual separation”.

Nine seconds later, at 0900:31 San Diego Approach told Kazy and Boswell about the presence of Flight 182, and reassuringly informed them that the much bigger aircraft had their Cessna in sight.

Shortly after that, the Cessna turned through 20 degrees to head due east, flying in exactly the same direction as Flight 182, just at a lower altitude.

Kazy and Boswell, having been told Flight 182 had them in sight, could reasonably assume the men in control of the jet had seen them change course.

They hadn’t. The light aircraft was now beneath the jet and out of sight of the men in the Boeing’s cockpit.

Flight 182, however, was not told by air traffic control about the Cessna’s change of direction.

The rules dictated that Flight 182, as the overtaking aircraft, was the one with the duty to keep “well clear”, whatever changes in course the Cessna made.

But, as the small pieces that would make a massive disaster began to slot into place, the men in the Boeing did not tell air traffic control they had lost sight of the Cessna.

At 0900:34 Flight 182 told Lindbergh Tower they were on the downwind leg for landing. The tower acknowledged and issued the reminder: “Traffic, 12 o’clock, one mile, a Cessna.”

At 0900:41 Captain McFeron asked “Is that the one we’re looking at?”

Fox answered: “Yeah, but I don’t see him now.”

Not knowing about the Cessna’s change of course, and therefore expecting it to have crossed beneath them, Captain McFeron told the tower: “I think he’s pass(ed) off to our right.”

The black box recorder would later reveal how, in the jet’s cockpit, there was a relatively relaxed discussion about the Cessna.

“Are we clear of that Cessna?” asked Fox, at the controls.

“Suppose to be,” said flight engineer Wahne.

“I guess,” replied Fox.

As they laughed, the vastly experienced Nelson added to the banter with the comment: “I hope.”

Eight seconds later, at 9.01am and 28 seconds, in the San Diego Approach control room, a conflict alert sounded.

But no-one did anything.

Later, the accident report would explain that at the time, air traffic control regulation did not require controllers to tell pilots of a conflict alert.

And as the controller explained, conflict alerts were fairly regular occurrences on the approach to the busy airport.

The alerts could be triggered when aircraft were in fact a safe distance of half a mile away from each other. And with the controller having been told 66 seconds earlier, at 0900:22, that Flight 182 had the Cessna in sight, he believed the necessary avoiding action had been taken.

And so, the two aircraft maintained their fatally converging courses, the Cessna climbing, the jet coming up fast behind it, and descending from its higher altitude.

At 9.01am and 31 seconds, Fox called for the landing gear to be lowered.

Seven seconds later, the cockpit area microphone recorded his voice saying: “There’s one underneath.”

At 9.01 am and 39 seconds Fox said: “I was looking at that inbound there.”

Then at 0901:45 Captain McFeron let out an exclamation that on the recording sounded like “whoop!”

Then Fox, the man at the controls, yelled “Aghhh!”

The impact came a second later, at 9.01am and 47 seconds.

At first, the air accident report attributed the probable cause of the disaster to the human error of PSA 182’s flight crew in not sticking to visual clearance separation procedures, and in particular failing to inform air traffic control that they had lost sight of the Cessna.

Only one lesser, contributory factor was listed: the procedures that allowed air traffic controllers to use visual protocols when they could have used radar separation procedures.

There was, though, a lone dissenting voice on the four-man panel: that of Brooklyn-born, former Second World War Navy pilot Francis H. McAdams.

In his sharply worded, skilfully argued minority report, McAdams insisted it was “neither acceptable nor sufficient” to list “the inadequacies of the air traffic control system” as merely contributory.

“In my opinion,” he wrote, “The concept of see-and-avoid is outmoded and should not be used in high volume areas. Both aircraft should have remained under positive radar separation since it was available and could have provided safe separation. The failure to do so must be considered causal.”

And so it eventually was. In 1982 the report was amended to make the decision not to use radar separation a second probable cause, alongside the alleged shortcomings of the Boeing’s flight crew.

Three new contributory factors were added: the failure of ground control to advise Flight 182 of the Cessna’s change of course; “the failure of the pilot of the Cessna to maintain his assigned heading”; and “the improper resolution by the controller of the conflict alert”.

That, then, was the end of the official aircraft accident report. Except for one haunting postscript.

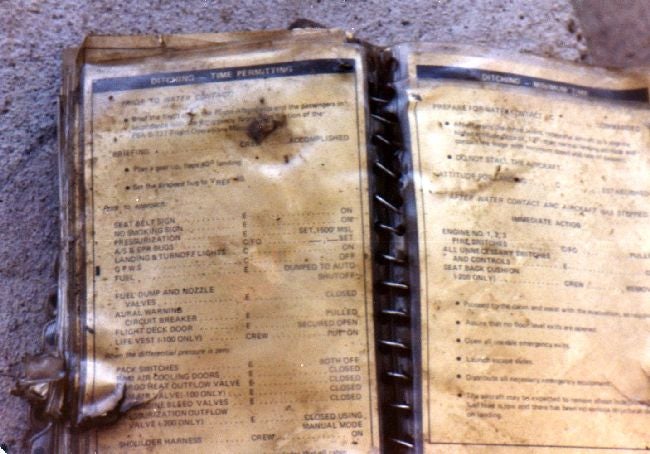

Contained in an appendix was the transcript of the recording of the final sounds from Flight 182's cockpit, as preserved by the aircraft’s black box.

It showed that the cockpit area microphone did not stop recording on impact with the Cessna.

Six seconds in to the jet’s uncontrollable, 17-second descent, first officer Fox can be heard telling his captain: “We’re hit man, we are hit”.

The stall alarm starts sounding. Captain McFeron can be heard saying, possibly to his passengers, “Brace yourself.”

Then, inside the cockpit of the doomed plane, someone – his voice was never positively identified – shouts “Ma, I love yah.”

Half a second later, the recording stops.