As she puts the finishing touches to her habit, Sister Clarita, a Mexican immigrant living in Los Angeles, tells me that there are more than 3,000 LGBT+ nuns around the world. They’re part of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, an international network of activists who identify as secular nuns. From Sydney to Los Angeles to Huddersfield, these queer nuns swap crucifixes for Pride memorabilia as they get to work on their mission: to promote universal joy and remove any sense of shame felt within the LGBT+ community.

In the UK, official houses for the sisterhood exist in Manchester, Edinburgh and Cardiff, with more on the way in Glasgow and Bristol. Their modern take on nunneries allows sisters to take part in their mission alongside their ordinary lives – performing, attending protests, handing out free condoms and sexual health leaflets whenever and wherever is convenient. “There’s something of the secular self in the nun and always something of the nun in our secular self,” explains Sister Polly Amarosa, who in 2021 founded the Trans Pennine Travelling Sisters – a group of queer nuns who carry out their work along the Trans Pennine Trail.

But they’re not real nuns, I hear you say, as your eyes skim across the photos of sisters in drag. I admittedly thought the same when I first met Sister Polly, a trans man and radical feminist who spoke frankly and hilariously about BDSM and patriarchal pleasure. Surely nuns as we know them haven’t gone completely wild?

“We’re what the Catholic Church should be, or should’ve been 50 years ago,” Sister Polly says. To become a sister, you go through a process that takes inspiration from the ordination process of the Catholic Church. Fully professed sisters start as aspirants, or someone who aspires to be a sister. After meeting with other sisters and talking about the kind of work you’d like to do, you become a postulant – traditionally this means someone seeking entrance to a religious order. When you’ve performed acts of ministry or activism, your house will meet to decide whether to elevate you to a novice. And finally, after you’ve completed a formal ceremony to commit to the vows of the sisterhood – something called a “vestition” – you become a sister. Light work. “It’s about enabling LGBT+ people who’ve experienced the negative aspects of religion to have a symbolic system that blesses them, and helps them heal,” Sister Polly says.

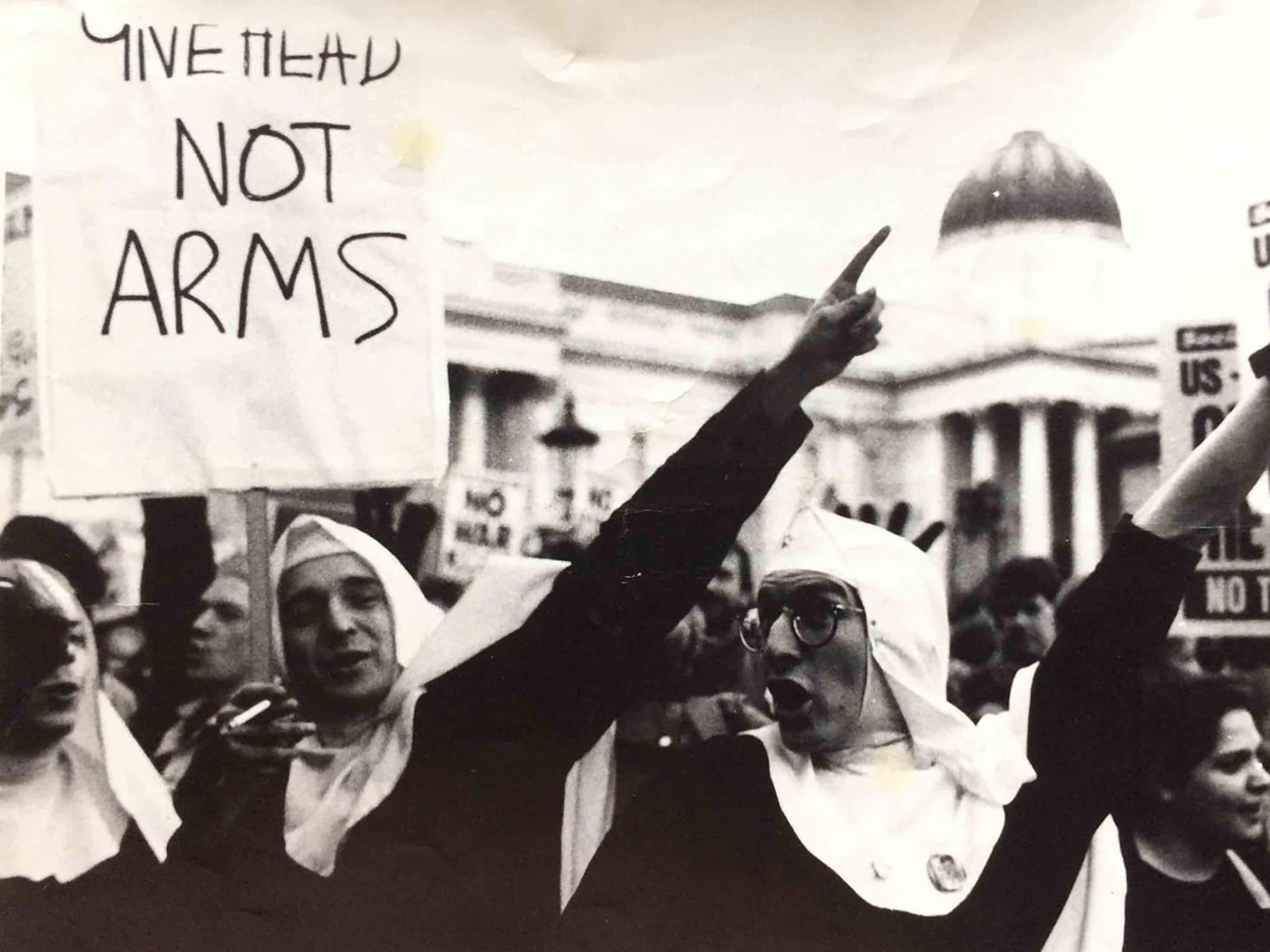

The idea of a queer, secular sisterhood began in late Seventies San Francisco. In a district presided over by Harvey Milk, the first openly gay man to be elected to public office, queer men began wearing nun habits in protests. A few years later, groups of gay men in London wore habits to protest against the UK government’s treatment of the Aids crisis.

Sister Polly tells me that the sisterhood’s arrival in the UK is greatly contested – the Aids crisis meant that many of the original sisters died early, taking the British history of the sisterhood with them. There is speculation that a secular Australian nun brought the idea to London in 1991, but others swear they witnessed nuns protesting with the Gay Liberation Front in the Eighties.

Sainthoods are about honouring our heroes, not with ornaments of empire but with the love of our community

Whatever the truth, Mother Mandragora – who is known as Kell Farshea when they’re out of their habit and identifies as non-binary – first encountered the sisterhood in the Nineties while working as a press officer for Act Up, the grassroots political group founded to end the Aids pandemic. “People didn’t expect articulate, political analysis from gay men dressed as nuns,” they tell me. “It was an opportunity to put a different perspective into the public domain. It may look ridiculous, but no one can deny we were confrontational.”

Their habits were an asset at times, too. Farshea remembers protesting outside of a private members’ club in the Eighties where notorious Conservative activist Mary Whitehouse was due to give a speech, and starting to chant when Whitehouse took to the stage. It was enough for the police to threaten them, before a passer-by shouted: “Are you really going to arrest a nun?” Farshea smiles at the memory – the police let them be. “Being a sister gave me extra power in that situation.” Life as a Sister of Perpetual Indulgence wasn’t just fuelled by anger back then, either. “It was extremely liberating,” Farshea adds. “It gave me an opportunity to explore aspects of femininity that were closed off to me at the time.”

A key part of the sisterhood’s mission is to grant sainthood to often unsung heroes in the LGBT+ community. One of the most memorable sainthoods, which Farshea attended, was that of the filmmaker, artist and gay rights activist Derek Jarman. “Derek was a queer hero who was our first and most obvious choice for our saint,” they tell me.

Last year in Huddersfield, Sister Polly sainted photographer Ajumu X, now Patron Saint of Darkrooms, for his boundary-crossing work capturing black, queer bodies. Though much of what the sisters do has a comedic or theatrical bent, often involving the house’s best orator and a flurry of crude puns, sainting is far from a religious parody. “Most times when we talk about LGBT+ people, they’re already dead, they’re in the past,” Farshea says. “It’s about honouring our heroes, not with ornaments of empire but with the love of our community.” Sainthood means the work, joy and resistance of queer icons becomes immortal.

The nuns have also grown from an organisation largely oriented around cisgender gay men to one of enormous diversity. Sister Clarita is the first Mexican in the sisterhood, and there are now a lot more trans and non-binary sisters. It’s especially important at a time in which the rights of trans people have become a target for lawmakers – a Scottish bill to streamline the process of changing gender was blocked in January 2023, and only a small number of American states aren’t currently introducing bills designed to restrict trans rights. The Trans Pennine Travelling Sisters recently attended a Trans Day of Visibility event organised by Trans Leeds, where they offered saintings and, importantly, a listening ear. Last year, they attended a protest in York opposing the government’s decision not to ban conversion therapy for trans people, handing out tea bags and a note to say, “Keep the T in LGBT”. Plans to outlaw the practice have since been extended to include the trans community. Sisters in Los Angeles are also currently trying to improve political engagement, encouraging those traditionally isolated from the political sphere to vote in upcoming local elections.

Most significantly, though, the sisterhood embrace their position as role models. Novice Ann Ahmana Do Doo from the Glasgow mission tells me about a time she took part in a human library project at a primary school in Scotland. Children between eight and 10 could ask questions of people from different backgrounds who’d been invited to the school. In her habit and makeup, Novice Ann spoke about “the joy of existing how you wish to be”. Over a decade later at Cardiff Pride, she heard someone shout her name. It was one of the same children she’d spoken to years earlier, only now older and trans.

“We hugged and cried a bit,” she remembers. “They were so happy. They found the joy that I’d been speaking about.” She says that what she aimed to do back then was provide someone with “the skillset” to identify what happiness is. “That’s what we teach each other as nuns, and anybody we meet. It justified my existence. The fact I helped a human being develop in a direction that they chose, that they wanted, is why I’ll probably do this for the rest of my life.”