Criminal prosecution of former President Donald Trump and his allies could result from at least one of multiple investigations.

These include the Aug. 8, 2022, seizure of documents from his Florida home by the FBI, continued progress in a Georgia state investigation into Republican election tampering and the ongoing revelations of evidence presented by the congressional committee investigating the Jan. 6 insurrection.

While charging a former president with a criminal offense would be a first in the United States, in other countries ex-leaders are routinely investigated, prosecuted and even jailed.

In March 2021, former French President Nicolas Sarkozy was sentenced to a year in prison for corruption and influence peddling. Later that year, the trial of Israel’s longtime Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu related to breaches of trust, bribery and fraud while in office commenced. And Jacob Zuma, the former president of South Africa who was charged with money laundering and racketeering, will likely face trial in May 2023 after years of delays.

At first glance, prosecuting current or past top officials accused of illegal conduct seems like an obvious decision for a democracy: Everyone should be subject to the rule of law.

But presidents and prime ministers aren’t just anyone. They are chosen by a nation’s citizens or their parties to lead. They are often popular, sometimes revered. So judicial proceedings against them are inevitably perceived as political and become divisive.

Destabilizing prosecutions

This is partly why U.S. President Gerald Ford pardoned Richard Nixon, his predecessor, in 1974. Despite clear evidence of criminal wrongdoing in the Watergate scandal, Ford feared the country “would needlessly be diverted from meeting (our) challenges if we as a people were to remain sharply divided over” punishing the ex-president.

Public reaction at the time was divided along party lines. Today, some now see absolving Nixon as necessary to heal the nation, while others believe it was a historic mistake, even taking Nixon’s deteriorating health into account – if for no other reason than it emboldens future impunity of the kind Trump is accused of.

Our research on prosecuting world leaders finds that both sweeping immunity and overzealous prosecutions can undermine democracy. But such prosecutions pose different risks for older democracies such as France and the U.S. than they do in younger democracies like South Africa.

Mature democracies

Strong democracies are usually competent enough – and the judicial system independent enough – to prosecute politicians who misbehave, including top leaders.

Sarkozy is France’s second modern president to be found guilty of corruption, after Jacques Chirac in 2011 for kickbacks and an attempt to bribe a magistrate. The country didn’t fall apart after either conviction. Some observers, however, say that Sarkozy’s three-year prison sentence was too harsh and politically motivated.

In mature democracies, prosecutions that hold leaders accountable can solidify the rule of law. South Korea investigated and convicted five former presidents starting in the 1990s, a wave of political prosecutions that culminated in the 2018 impeachment of President Park Geun-hye and, soon after, the conviction and imprisonment of her predecessor, Lee Myung-bak.

Did these prosecutions deter future leaders from wrongdoing? For what it’s worth, Korea’s two most recent presidents have so far kept out of legal trouble.

Overzealous prosecution versus rule of law

Even in mature democracies, prosecutors or judges can abuse prosecutions. But overzealous political prosecution is more likely, and potentially more damaging, in emerging democracies where courts and other public institutions may be insufficiently independent from politics. The weaker and more beholden the judiciary, the easier it is for leaders to exploit the system, either to expand their own power or to take down an opponent.

Brazil embodies this dilemma.

Ex-President Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, a former shoeshine boy turned popular leftist, was jailed in 2018 for accepting bribes. Many Brazilians thought his prosecution was a politicized effort to end his career.

A year later, the same prosecutorial team accused the conservative former President Michel Temer of accepting millions in bribes. After his term ended in 2019, Temer was arrested; his trial was later suspended.

Both Brazilian presidents’ prosecutions were part of a yearslong sweeping anti-corruption probe by the courts that has jailed dozens of politicians. Even the probe’s lead prosecutor is accused of corruption.

Depending on one’s perspective, Brazil’s crisis reveals that nobody is above the law or that the government is incorrigibly corrupt – or both. With such confusion, it becomes easier for politicians and voters to view leaders’ transgressions as a normal cost of doing business.

For Lula, a conviction didn’t end his career. He was released from jail in 2019 and the Supreme Court later annulled his conviction. Lula is now leading the 2022 presidential race against current Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro.

Stability versus accountability

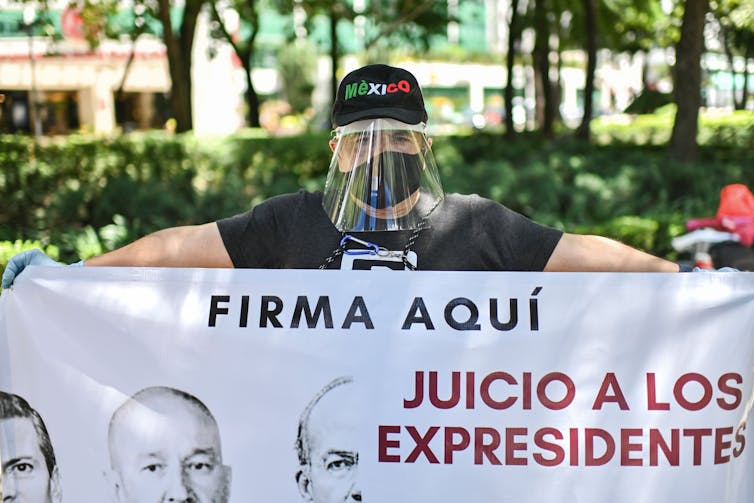

Historically, Mexico has taken a different approach to prosecuting past presidents: It doesn’t.

During the 20th century, Mexico’s ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, established a system of patronage and corruption that kept its members in power and other parties in the minority. While making a show of going after smaller fish for petty indiscretions, the PRI-run legal system wouldn’t touch top party officials, even the most openly corrupt.

Impunity kept Mexico stable during its transition to democracy in the 1990s by placating PRI members’ fears of prosecution after leaving office. But government corruption flourished, and with it, organized crime.

That may be changing, though. In early August 2022, Mexican federal prosecutors confirmed that it has several open investigations into former PRI President Enrique Peña Nieto for alleged money laundering and election-related offenses, among other crimes.

Mexico is far from the only country to overlook the bad deeds of past leaders. Our research finds that only 23% of countries that transitioned to democracy between 1885 and 2004 charged former leaders with crimes after democratization.

Protecting authoritarians – including those who oversaw human rights violations – may seem contrary to democratic values, but many transitional governments have decided it is necessary for democracy to take root.

That’s the bargain South Africa struck as apartheid’s decades of segregation and human rights abuses ended in the early 1990s. South Africa’s white-dominated government negotiated with Nelson Mandela’s Black-led African National Congress to ensure outgoing government members and supporters would avoid prosecution and largely retain their wealth.

This strategy helped the country transition to majority Black rule in 1994 and avoid a civil war. But it hurt efforts to create a more equal South Africa. As a result, the country has retained one of the world’s highest racial wealth gaps.

Corruption is a problem, too, as former President Zuma’s prosecution for lavish personal use of public funds shows. But South Africa has a famously independent judiciary. Despite pushback from some African National Congress stalwarts and several legal appeals, Zuma’s prosecution continues. And it may yet deter future misdeeds.

How mature is mature?

Israel is partly a testament to the rule of law – and partly a cautionary tale about prosecuting leaders in democracies.

Israel didn’t wait for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to leave office to investigate wrongdoing. But the court process was fraught with delays, in part because Netanyahu used state power to resist what he called a “witch hunt.”

The trial triggered protests by his Likud party. Netanyahu tried unsuccessfully to secure immunity and stall. He was even reelected while under indictment, and his trial is not over yet.

If Trump is criminally prosecuted, the process would reveal something fundamental about American democracy. Whatever the outcomes, they would be a matter of both law – and politics.

This is a substantially updated version of an article originally published on March 16, 2021.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.