Nigel James mimics the impact of the car that crashed into his motorbike with a clap. “Broken ankle,” he says.

The father of two of the country’s brightest footballing prospects, Reece (Chelsea) and Lauren (Manchester United), is attempting to explain the method of guiding his children to the point of being elite professionals with a decade of top-flight football ahead of them.

At its root, it is the rare perspective of having seen the sport as a player, a coach and a father and a lens that’s brought both elation and heartache. But, ironically, that road which began on an estate in Brixton and led to leafy Richmond was changed irrevocably by one cruel traffic accident en route.

***

The Player

As James hobbled to the pavement, crippled by the pain of an injury that would set his short career back by months, a realisation dawned: “I’d fallen out of love with football,” he says.

A thickset defender plying his way at Aldershot Town, the 20-year-old had already trialled at Southampton, trained with Chelsea’s David Collier in Battersea, and spent seasons at Luton, Woking, and Crawley before a deadline day move to the fourth-tier Saints. Treading the tightwire between success and survival in England’s academy systems had already been wearying and, with an imposing physique that belied his age and a lack of support in the dressing room, he’d grown despondent.

“When you’re young and you’re not playing, you realise football can be a lonely place,” he says. “When you don’t click into a group, you can feel like an outsider; like you’re an alien. That one-size-fits-all approach, it sort of made me hate football and that’s what really pushed me into wanting to be a coach.”

Around the same time, James’ first child, Joshua, was born. A young father living in a small flat on Somerleyton Estate with bills falling through the letterbox, a few former teammates at Woking offered him the chance to help out with coaching jobs in the area. Studying under Gwynne Berry, an academy coach at Crystal Palace and later West Ham, James took his experiences as a player and tried to prepare a younger generation for them, absorbing knowledge and visiting soccer schools up and down the country. By the time his ankle had recovered, he was dreading returning to training.

“I loved coaching and the more I did it, the harder it felt to go back to playing,” he says. “[After my experience at Aldershot], you sit and think to yourself that the next experience is going to be just like the bad one you’ve had; that things will be exactly the same and so, to protect yourself, you stay out of it. People always talk about football being fun, but the word fun can be fake. When I was coaching, it stayed real.”

***

The Coach

Now a new father, James decided to give up on his career as a player. Instead, in the mornings, he’d drive Joshua five miles from Brixton to a private nursery sheltered away from the estate, helping out with coaching jobs until the family had saved up enough money to move for a quieter life in Richmond. At the time, a spate of new schools had opened in the borough and, after word spread that he’d started his own coaching academy, he was spending every day of the week helping to train their younger age group.

Between those daytime training sessions and endless drills with Reece and Lauren behind the house each evening, James had gathered a pool of the area’s best local talent and formed an U8s team, including the likes of Zech Medley (who went on to play for Arsenal), Conor Gallagher (Chelsea), Ian Carlo Poveda (Manchester City), Alfie Doughty (Charlton), Jack O’Connor (Crystal Palace) as well as his own children. They stormed competitions and scouts arrived in their hoards, along with invites to play against Chelsea, Arsenal, Crystal Palace, Reading and Charlton. Before long, every single member of the side was signed to professional academies. “We’d go to these clubs and give them a real good game,” James laughs. “Sometimes we’d even win.”

Over the course of James’ two decades as a coach, 24 players he’s trained have gone on to sign professional contracts and over 60 have spent a significant number of years in the academy system. He’s worked as a scout at Fulham, Reading and Tottenham but while there are techniques – ingraining possession-based football, a fixation on close control and an urgent mentality – he says there are few secrets in a sport where talent is overtaken by hard work.

Yet it’s those who haven’t necessarily had such success that James stresses are closest to him. The children who despite not having ‘made it’, he can take an overwhelming sense of pride in helping to save from falling down the wrong path. He sees echoes of his younger self in some of them and has become the type of footballing father-figure he suffered without at Aldershot. “It’s making a difference for people who could have gone the other way,” he says. “That’s what people don’t see and perhaps don’t understand but that’s what’s most important. I’ve had kids come over here alone and I’ve had to open my arms to them. You’ve got to try and make people feel like it’s all or nothing because if things aren’t going well and the support isn’t there, the child will suffer.”

***

The Father

Are you a protective father?

“I’m a Rottweiler,” James barks.

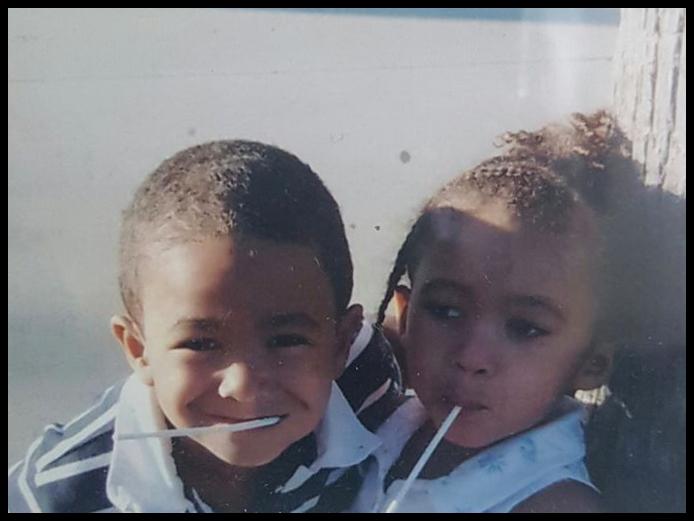

Since the day he began training his children in the park behind their house, James has coached Joshua, Reece and Lauren with the ambition of them becoming professionals. As a family, their lives orbit around the sport. With Reece 19 and Lauren 17 years old, he has finally been able to take a step back from choreographing drills and fitness routines as the family’s hard work has been realised. “Coaching them is definitely over,” he stresses with varying glimmers of relief, acceptance and pride. “As a parent in football, you have to know when to separate.

“I’ll still go to their matches,” he says of a year spent trekking up to Manchester and across to Wigan to watch each game. “It’s a proud moment for me. If you took my blood pressure after a match you’d have thought I was the one playing. As a parent, all I’ve ever wanted is to see them do what they want to in life.”

Instead, in a world where success burns brighter and the multitude of agencies, contracts, sponsorships and offers becomes greater, for parents like Nigel their role is more that of a parental bodyguard, protecting from outside pressures and preserving the sacrifices made to this point. “You’ve got to try and keep these things away from the kids as much as possible so they can concentrate on their careers.”

“There’s a lot of greed in football. The temptation of money, what it does to people, it boils down to trust. Do you blame yourself if something goes wrong?” James asks himself. “It can be very painful but you can’t because otherwise you’d go through life without believing in anyone. There’s a lot of good people in football, there are also some bad ones too. Everyone knows the money is life-changing. Some people can deal with that, others can’t.”

***

For a father, the burden of hard work eases with age. James’ years of effort have aligned and, within the next five years, Reece and Lauren could well be two of the most prominent footballers in the country. And yet, James’ work is far from easing off. Last year his under-18s side won the treble and he needs to replace his captain who left this summer to train with Deportivo La Coruna before joining Watford for pre-season. Another has joined Reading while three more made it to Clermont in France. Meanwhile, there’s a group of under-8s needing to prep for the new season.

“People ask ‘how do you have the energy to still run around and coach an eight-year-old?’” He says. “Well, it’s obvious. isn’t it? This is my job, just like the kids have theirs. This is my passion. It’s what I do.”

The phone rings; Reece is calling to give his dad an update on his injury. He’s just been able to sprint properly for the first time in weeks. Seconds later, a text chimes asking for advice; this time from Lauren who’s away with Manchester United on their pre-season tour of Norway. The role of being a father and coach often translate as one. “I can’t imagine a day I’ll ever stop,” he smiles.