Litigants and their lawyers often seek to retroactively seal or pseudonymize cases. Courts sometimes allow this, but often reject it. In particular, that a case has settled is generally not seen as a basis for retroactively sealing it, even when the case settles shortly after filing without any substantive decision from the court; see, e.g., Bernstein v. Bernstein Litowitz Berger & Grossmann (2d Cir. 2016):

The fact that a suit is ultimately settled without a judgment on the merits does not impair the "judicial record" status of pleadings. It is true that settlement of a case precludes the judicial determination of the pleadings' veracity and legal sufficiency. But attorneys and others submitting pleadings are under an obligation to ensure, when submitting pleadings, that "the factual contentions [made] have evidentiary support or, if specifically so identified, will likely have evidentiary support after a reasonable opportunity for further investigation or discovery."

In any event, the fact of filing a complaint, whatever its veracity, is a significant matter of record. Even in the settlement context, the inspection of pleadings allows "the public [to] discern the prevalence of certain types of cases, the nature of the parties to particular kinds of actions, information about the settlement rates in different areas of law, and the types of materials that are likely to be sealed." Thus, pleadings are considered judicial records "even when the case is pending before judgment or resolved by settlement."

And courts are especially reluctant to retroactively seal or even retroactively redact documents that had been available in the open record for months or year, see Gambale v. Deutsche Bank AG (2d Cir. 2004):

[W]e think that it was a serious abuse of discretion for the district court to refer to the magnitude of the settlement amount—theretofore confidential—in the Unsealing Order. But however confidential it may have been beforehand, subsequent to publication it was confidential no longer. It now resides on the highly accessible databases of Westlaw and Lexis and has apparently been disseminated prominently elsewhere. We simply do not have the power, even were we of the mind to use it if we had, to make what has thus become public private again. The genie is out of the bottle, albeit because of what we consider to be the district court's error. We have not the means to put the genie back….

This is generally so when information that is supposed to be confidential … is publicly disclosed. Once it is public, it necessarily remains public…. "Once the cat is out of the bag, the ball game is over."

This has come up recently, in Singh v. Amar (C.D. Ill.) (see "No First Amendment Violation in Requiring Law Student to Meet with 'Behavior Intervention Team Related to … allegedly 'threaten[ing] … administrators, ma[king] female instructors and students uncomfortable, and show[ing] signs of 'disjointed' thinking'"). Plaintiff's lawyer had filed the lawsuit as a John Doe lawsuit, apparently without filing a written motion for leave to proceed pseudonymously (and including unredacted exhibits that gave plaintiff's real name). It appears that the lawyer made an oral motion along those lines, as well as to seal the record, which was denied; and the judge immediately "directed [the Clerk] to change the docket to reflect Plaintiff's name." Now the case has settled, and plaintiff seeks to have the case sealed or, in the alternative, pseudonymized; part of the argument is that plaintiff was badly advised by his initial lawyer:

Plaintiff's Motion to Proceed Under Pseudonym should also be granted because Plaintiff was given improper legal advice from the beginning of this litigation. Plaintiff's former counsel, who is now suspended from the Illinois bar, chose to file exhibits without redactions, revealing Plaintiff's identity even before Plaintiff's pseudonym status was denied. Defendants opposed the initial motion largely based on the unredacted filings. Accordingly, both parties respectfully request in the absence of a sealing of the entire Court record, that Plaintiff's name be replaced with "John Doe" and that the parties be permitted to re-file the exhibits identified by ECF numbers 1-3, 1-6, 1-7, 5-1, 7-1, 7-2, 7-3, 7-4, 7-6, 9-1, and 13, which currently contain personally identifying information….

[The] Motion to Proceed Under Pseudonym should [also] be granted because Plaintiff was not given an opportunity to discontinue his lawsuit prior to the Court revising the docket with Plaintiff's legal name. Given the potential harms resulting from disclosure as discussed above, Plaintiff likely would have discontinued his lawsuit once he was denied pseudonym status. However, this Court entered a text order denying Plaintiff pseudonym status and immediately directed the clerk to revise the docket with Plaintiff's legal name for the public to see. Plaintiff was not informed by his legal counsel prior to filing suit of the potential for immediate disclosure of his name if his Motion to Proceed Under Pseudonym was denied. Accordingly, the docket should be revised, and Plaintiff's legal name should be replaced with "John Doe."

The new lawyer also offers this to argue why pseudonymity should have been granted at the outset:

Plaintiff has demonstrated sufficient grounds to seal the entire record in this case for numerous reasons. First, as noted above, both parties are jointly moving to seal the record and have reached a confidential settlement in this matter. As such, the case is resolved in its entirety, and the parties will subsequently seek to dismiss this case with prejudice. There will be no further litigation in this matter, so there will be no records that are hidden from the public that have not already been made visible. Accordingly, sealing the Court record does not disturb the preference for open judicial proceedings, as this case has been litigated to the fullest extent in the public domain.

Second, Plaintiff's privacy interests in this case predominate the presumption that judicial records be open to the public. Plaintiff's claims for relief by their very nature contain details of a highly sensitive and intimate nature—namely allegations of mental health, paranoia, and school safety. Plaintiff does not simply highlight that the disclosure of his name would result in public humiliation or embarrassment. Rather, Plaintiff highlights the extremely sensitive nature and privacy issues that could be associated with being wrongfully linked to allegations of safety concerns requiring behavioral intervention.

To that end, Plaintiff alleges that his federal constitutional rights were violated by Defendants—which Defendants dispute—when the University violated his freedom of speech as a result of the allegations. Surely this Court can take judicial notice of the sensitive topic of school safety, given the numerous tragedies and lives lost recently by violence within schools. The nature of mental health and safety concerns (all of which Plaintiff disputes in this case), and the allegations stemming therefrom, are such that Plaintiff will suffer extreme harm throughout his lifetime. Indeed, the Seventh Circuit has stated that where medical or mental health issues and records are such that they would be highly embarrassing and damaging to the average person, a sealing of the court record, either in whole or in part, may be warranted. See Doe v. Blue Cross & Blue Shield United of Wisconsin, 112 F.3d 869, 872 (7th Cir. 1997) ("Should 'John Doe' 's … records contain material that would be highly embarrassing to the average person yet somehow pertinent to this suit and so an appropriate part of the judicial record, the judge could require that this material be placed under seal."). Additionally, it is in the interests of Defendants to have the record sealed in light of Plaintiff's allegations of improper conduct by the University and its officials.

Plaintiff is currently a law student at the University of Illinois, with a job offer from an AmLaw 100 law firm. If this law firm, or any firm to which Plaintiff may opt to apply to in the future, were to conduct a background check or internet search of Plaintiff's name, Plaintiff would immediately be connected to this lawsuit as well as the damaging statements that were made throughout the course of litigation. The allegations and statements would likely tarnish Plaintiff's professional reputation, and derail Plaintiff's legal future before it even begins. Given that Plaintiff disputes these assertions and the parties have reached a settlement, there can be no public interest in these filings. Accordingly, Plaintiff's privacy concerns outweigh the preference for open judicial proceedings in this case….

Here is an excerpt from the allegations about the student, from the court record; as always, please note that these were just allegations, and there has been no adjudicated about whether they are accurate:

Singh[] was aggressive in his communications with his female fall law professors, including multiple combative emails with one professor in particular. After exams, the accusatory emails continued to that professor and to others. This semester, he has continued his aggressive emails to one female professors and send aggressive emails to other female professors on his schedule. In person meetings between administration and the student to address his behavior resulted in his use of aggressive and combative in tones and communication. Immediately thereafter he sent another combative communication to a female professor. Most recently, he sent communications to a student's significant other accusing her of making comments about him even though she is not a law student and did not know him. Then to her boyfriend that is a classmate, he made comments that were nonsensical alleging FBI conspiracies with the College and other erratic behavior. A meeting with the Deans was held with him and he responded erratically and with an aggressive tone and with threats. There was a lengthy discussion about his belief that FBI had infiltrated the university to secure his records, had purchased buildings around his apartment for surveillance of him, and had infiltrated the It services. He also issues threats stating that the college was heading into "dangerous territory" and that there would be harm to the institution. When asked about these threats, he became agitated and loud, claiming his words were twisted. He went on to refine words as harm and danger through "peaceful actions through the law." Attached to this document is a collection of representative samples of communications with … Singh including the student email referencing the FBI infiltration, but they do not include the continued aggressive emails to the year long professor because I am not presently in possession of them.

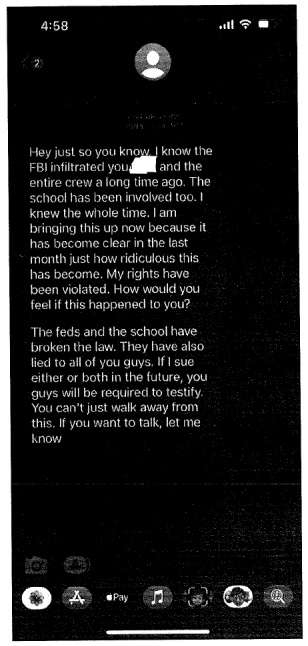

And here is the alleged text:

The post Professional Duty to Warn Clients About Risk of Reputational Harm from Filing Lawsuit? appeared first on Reason.com.