The last few weeks have seen a steady stream of news related to the new memoir written by Prince Harry, titled “Spare.” While much of the media attention has focused on his relationship with King Charles; Prince William; Catherine, princess of Wales; and Camilla, the queen consort, it is his admission to killing 25 members of the Taliban during his tour of Afghanistan that has come in for criticism from some royal commentators.

In an “era of Apaches and laptops,” Harry said he was able to say “with exactness” how many he had killed. “It seemed to me essential not to be afraid of that number. So, my number is 25. It’s not a number that fills me with satisfaction, but nor does it embarrass me.” Prince Harry also discussed his psychological mindset regarding these deaths, and how he was “programmed” to cope with them. Additionally, he said that he saw them as chess pieces in “the heat and fog of combat,” and not “as people.” He stated that he was trained to “other-ize,” and that while he recognized that as problematic, he “saw it as an unavoidable part of soldiering.”

Although it may have been intended as an honest appraisal of his own experiences in war, research shows that Harry’s words cannot convey how others in similar situations reflect on having killed in conflict.

Moreover, some have criticized the admission for sounding like counting “notches on a rifle butt.” Harry, however, has accused the media of taking his words out of context. Appearing on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert,” he said, “I think one of the most dangerous lies that they have told is that I somehow boasted about the number of people I have killed in Afghanistan.”

Outside the global consequences of his words, as a psychologist who specializes in military decision-making, I am most concerned that Prince Harry projects a certainty that is not often afforded those who make decisions in the “heat and fog” of combat.

War is not a chess game

War involves operating in a hybrid environment against an adaptive enemy that often operates in and around a local civilian population. Chess is a game that involves two sides, in which all moves are predefined, and all of the information about the pieces on the board is known and visible.

For a 2019 book titled “Conflict: How Soldiers Make Impossible Decisions,” Laurence Alison, Joseph Moran and I interviewed soldiers about the decisions that they made during their tours in Afghanistan. What we found was that military decision-making is a rarely as simple as “bads” and “goods,” as Harry writes, or simply being programmed to remove people like chess pieces.

This research is supported by a host of other studies we have completed on high-stakes decision-making with emergency responders that paints a far more complex picture of the cognitive process and the skills required for people to make decisions amid uncertainty.

Our studies of expert decision-makers emphasize that good decison-making is an adaptive skill that requires the individuals to be able to handle complexity, juggle competing values, handle time pressure and know when to act. They also need to ask the right questions and, indeed, to know when to abandon a course of action and seek to do something new.

To present high-stakes military decisions as a two-sided game of chess creates a false impression of certainty that few soldiers are afforded when making decisions.

A further issue is the narrative of “learned detachment.” This idea minimizes the very real psychological harm that soldiers face when making complicated moral decisions at war. While the costs of post-traumatic stress disorder in those who have served in war are widely known, psychologists are focusing specifically on the forms of trauma that are caused by having to make difficult, morally laden decisions under conditions of uncertainty.

Most notably, soldiers can suffer moral injury. Moral injury is defined by Brett Litz, a renowned expert on PTSD, as the result of a situation in which someone perpetrates or fails to prevent an act that transgresses a deeply held moral belief. Such injury is especially likely when an individual navigates decisions involving sacred or protected values, such as the need to protect life, which often emerge amid military conflict.

The costs of war

Wars carry a significant human cost. I worked with the journal Science to analyze the civilian casualty data from Afghanistan between 2009 and 2013. In my research I found that in 2013 alone, the International Security Assistance Force, a multinational military mission, recorded that at least 1,685 Afghan civilians were killed and some 3,554 wounded.

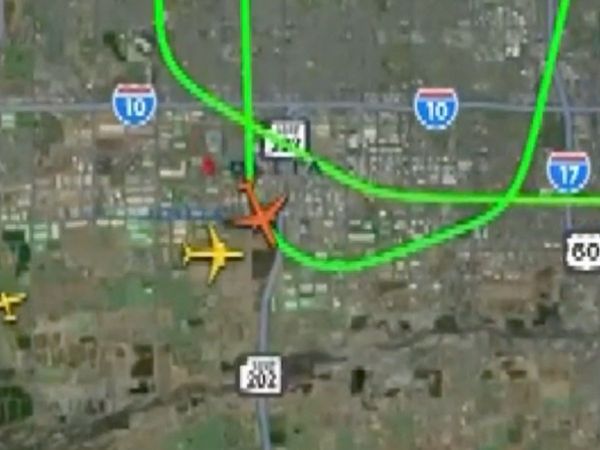

It was the highest number of civilian casualties since rigorous counting began in 2008. The total number of civilians killed from 2001 to 2021 is estimated to be over 46,000. Furthermore, our analysis showed that even as civilian casualties decreased overall, casualties caused by air power, such as Apache helicopters, remained high.

Prince Harry’s words can, I believe, fuel perceptions of a military insensitive to the human consequences of their actions and show a failure to respect the value of human life. Furthermore, presenting decisions of killing with such psychological and moral certainty does little to help current or future soldiers prepare themselves psychologically for the realities of war.

Neil Shortland receives funding from the National Science Foundation, Army Research Institute, Department of Defense, National Institute of Justice, Department of Homeland Security, and the United Kingdom Ministry of Defense.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.