Insulin, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, poop. You likely don’t think of the latter as medicinal, but there are good reasons to think that’s about to change. Last month, the FDA approved a fecal-based treatment for the first time. The drug, Rebyota, is approved for people with reoccurring bacterial infections of Clostridium difficile. C. diff. causes diarrhea and inflammation of the colon; it’s responsible for tens of thousands of deaths in the United States each year.

Despite the recent, first-time approval of the poop drug, doctors have been using fecal microbial transplants — in which stool from a donor is transplanted to change the microbial community in a recipient’s colon — for years. This approval is likely only the start of a promising future for prescription poop.

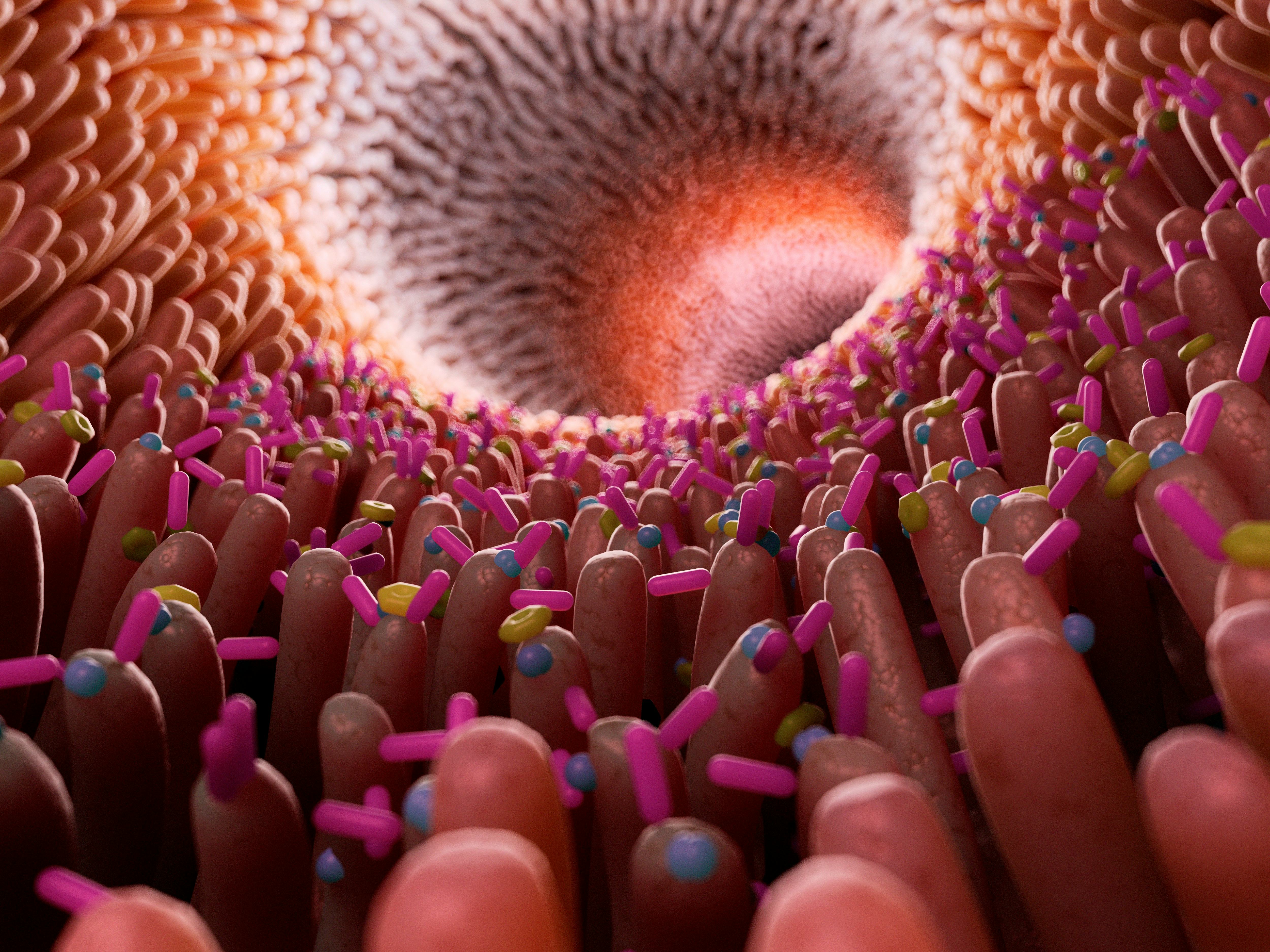

The gut microbiome is a colony of trillions of microbes, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi, living in our digestive tracts. Over the past decade, research into the gut microbiome has suggested that this colony contributes to a tremendous variety of conditions and diseases. Infusing a healthy donor’s gut microbes into a recipient’s gut may help mitigate diseases that are influenced by the gut microbiome, Ivan Vujkovic-Cvijin, assistant professor in Cedars-Sinai Divisions of Biomedical Science, Gastroenterology, and the F. Widjaja Inflammatory Bowel and Immunobiology Research Institute, tells Inverse.

What conditions might fecal-microbial transplant (FTM) treat?

Amy Barto, an associate professor of medicine at Duke and the director of its fecal microbiota transplantation program, tells Inverse that FMT works for C.diff infection when treatments like antibiotics don’t “because it makes use of an intact microbiome housed within the stool of a healthy donor to help restore the microbiome of the recipient,” she says. “Antibiotics used to treat the C. difficile bacteria only eliminate it in its active phase. The spores often remain and can reactivate causing recurrence of infection.” By that point, damage to the microbiome has already occurred and needs a more global approach, which FMT can provide.

In addition to C.diff., “there is relatively strong evidence that FMT works well for a subset of patients with ulcerative colitis,” Vujkovic-Cvijin says. For example, a 2015 randomized controlled trial published in the journal Gastroenterology found that after seven weeks of FMT, 24 percent of 70 people with ulcerative colitis were in clinical and endoscopic remission (meaning there’s no evidence of inflammation or disease) compared to five percent in the placebo group. A 2017 randomized controlled trial published in The Lancet found that after 8 weeks of treatment, 44 percent of the FMT group was in clinical remission from ulcerative colitis, and 54 percent had a clinical response to the treatments; in the placebo group, those numbers were 20 percent and 23 percent, respectively.

In addition to ulcerative colitis, initial research has shown “promising results for FMT in autism, cancer immunotherapy, and other conditions,” Vujkovic-Cvijin says. He cautions that while the small, early studies for the latter conditions are promising, larger, randomized controlled trials need to be performed before the efficacy of FMT can be concretely understood.

Why FMT may be able to treat conditions other drugs can’t

One of the reasons prescription poop may be so promising for difficult-to-treat conditions, Vujkovic-Cvijin says, is because many of the most challenging diseases are “multi-factorial,” meaning that multiple biological systems have gone awry or are dysregulated in a way that allows the disease to manifest. Many of the current treatments for such diseases only attack one part of the problem, resulting in a partially or even negligibly effective treatment.

In contrast, “The microbiome appears to have its own unique role in many diseases, and so it’s possible we can improve outcomes of treatment if we also address this important organ,” he says. “FMT is one of the first strategies the field has come across to alter the microbiome, and the promising results we see in a variety of diseases are exciting and push us to learn more.”

Barto agrees, saying that disruption of the microbiome, called dysbiosis, can lead to a cascade of events that can create a pro-inflammatory state affecting the whole body.

“This pro-inflammatory state can potentially influence multiple disease processes within the body,” she says. “In the future, FMT might be used in some form to modify or treat these or other conditions. This is the most exciting aspect of microbiome-based therapy: the chance to unlock its full potential.”

What will future treatments with poop look like?

While the newly approved FMT treatment for C. diff is in the form of a colonic enema, that won’t necessarily be its future form. FMT enemas make the most sense for diseases that primarily affect the colon, as does C. diff infection, Vujkovic-Cvijin says. Interestingly, he adds, FMT for recurrent C.diff doesn’t necessarily have to be in the form of an enema; “Seres Therapeutics also has a[n oral] microbiome product for recurrent CDI that will most likely be approved soon by the FDA.”

For conditions involving the small intestine, non-enema methods of delivery will likely be preferable, as “this community of microbes is both different from the colon and has distinct effects on our metabolism and immune system,” Vujkovic-Cvijin explains. “It’s likely that some diseases will benefit from altering small intestinal microbes, and thus nasogastric or pill-form microbiome therapeutics may be more efficacious for those diseases.”

These are routes that have been previously tested in some FMT studies. For example, a 2016 case study evaluated nasogastric administration of FMT in two patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) and diarrhea due to septic shock — a severe infection of the bloodstream. In nasogastric administration, a doctor inserts a tube through the nose and into the stomach, so they can more effectively deliver medication.

Doctors administered an infusion of sterile feces from a healthy donor through the patients’ nasogastric tubes. After it was administered, the patients’ fevers came down, and their other symptoms stabilized. Additionally, the researchers found that certain colonies of beneficial bacteria were increased in the patients’ gut microbiome following FMT.

How close are we to poop pills?

Vujkovic-Cvijin says he views FMT as a tool to assess the role of the microbiome in human disease.

“When we see FMT working for a particular disease, it gives us strong evidence that the microbiome is important in that setting and that we should continue our efforts to better understand its role,” he says.

One of the challenges of “microbiome-based therapy is that the success of clinical trials for more chronic conditions, like obesity or ulcerative colitis, appears to be short-lived,” Barto says. “This is likely due to the overall complexity of the microbiome, influenced by multiple ongoing internal and external factors.”

Additionally, as is the case with many treatments, especially ones that are still being fully understood, there are some risks to FMT. Vujkovic-Cvijin says those risks include “the inadvertent transfer of infectious microbes to recipients that went undetected in the healthy donor.” In some cases, those infectious microbes may have been held at bay by the donor’s health but would have a more significant impact on a less healthy person.

Additionally, some FMT is still a little unpredictable. “We don’t know which microbes in the recipient will colonize the host and which recipient microbes will be displaced,” he says. “Importantly, FMT also does not always displace the same microbes in each recipient.”

Once scientists learn which gut microbes are most important in a given disease, more targeted microbiome-mediated treatments than FMT can be developed.

Still, for complex and traditionally hard-to-treat conditions like ulcerative colitis, C. diff., and even potentially sepsis, prescription poop may be a cutting-edge and lifesaving treatment.