“Excellent decision.”

This was the reaction from English football great Gary Lineker to the announcement that the English Premier League has agreed to voluntarily “withdraw gambling sponsorship from the front of their matchday shirts”.

The league announced its decision after an “extensive consultation” with the UK government about its review of gambling legislation.

This decision was held up by the government as a key strategy to reduce children’s incidental exposure to gambling logos while watching football, in the UK’s gambling white paper released Thursday.

The white paper also identified the front-of-shirt ban as part of an effort to move towards “socially responsible” sports sponsorship.

Some UK campaigners cautiously welcomed the decision, saying it was an important admission from the Premier League that gambling advertising is harmful.

In Australia, some gambling reform groups said the measure was great news, and that Australian sporting codes should do the same.

However, in the following days, extensive criticism of the deal emerged. Public health experts and other stakeholders argued the measure was more about public relations than harm prevention.

Experts argued the ban would do little to tackle the entrenched relationship between the gambling industry and sport, and could even be a step backwards.

Many were concerned the measure deflected from the urgent need for comprehensive restrictions on gambling marketing – a measure widely supported to prevent the normalisation of gambling for children.

And the UK white paper did little to implement the comprehensive restrictions needed to reduce children’s daily exposure to gambling promotions.

A flawed approach

At the heart of the criticisms were that the decision, as well as related measures, did very little to address the proliferation of gambling marketing in sport.

The agreement:

only removes a small part of marketing on the front of matchday shirts. This leaves the door open for gambling branding to remain on other parts of the uniform, and on other kits

doesn’t address marketing or branding around sporting grounds

will not be implemented until the end of the 2025-26 season – hardly a sign of an urgent imperative to reduce the marketing of a harmful product

includes a promise to establish a “new code for responsible gambling sponsorship”

and seemingly ignores the evidence that voluntary codes serve primarily to protect the interests of advertisers, not the community.

The flaws with the Premier League’s decision highlight the significant problems with allowing those with vested interests to make decisions about what they’re prepared to engage in (or not) to protect the health of the public.

History shows these types of initiatives are rarely effective in reducing marketing for these products, or in protecting children.

Far from signalling progress, they serve to delay regulation that would protect public health. Voluntary measures and self-regulation are convenient for governments that don’t want to regulate a powerful industry. They form part of the narrative for government that “something is being done”.

Vested interests

In Australia, sporting organisations have a significant vested interest in making money from gambling products, sponsorships and promotions. Some, including the AFL, also receive a cut of gambling turnover on matches.

Peak sporting bodies claim sport delivers “long-term social, health, community and economic benefits”. While this is clearly true in many cases, it’s inconsistent with the stance many Australian sporting codes have taken on gambling. This is especially so given the irrefutable links between gambling and some of Australia’s most pressing health and social problems, including homelessness, family violence, criminality and mental health issues.

Instead of taking a strong stand to restrict gambling marketing, some sporting codes have continued to normalise the promotion of gambling products. We saw this all too clearly in the recent testimonies of the chief executives of the AFL and NRL to the current Australian Parliamentary Inquiry into Online Gambling.

The AFL and NRL chiefs, Gillon McLachlan and Andrew Abdo, did acknowledge concerns about gambling marketing, and said responsibility to the community was taken “seriously”. But both spoke repeatedly about the need for regulatory “balance” in relation to gambling.

McLachlan added: “I don’t believe that brand advertising per se is too much.”

But our research tells a different story.

Normalising gambling for kids

Children as young as eight have awareness and recall of gambling brands and promotions. They can name multiple gambling brands, describe the advertising in detail, and even tell us what colours certain gambling companies are. Young people tell us that much of this awareness comes from seeing gambling marketing in sport.

The gambling industry is also becoming more creative in linking gambling with sport. This includes promotions on platforms such as TikTok. Sportsbet chief executive Barni Evans justified these promotions by telling the parliamentary inquiry “we only work with partners such as TikTok who have reliable and robust age-gating technology”.

Learning from tobacco control

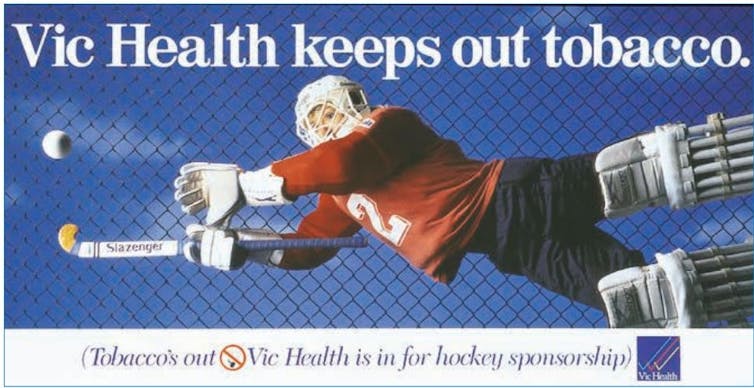

Government action is clearly the most effective intervention in curbing marketing for harmful products. That’s why governments took decisions about advertising and sponsorship away from the tobacco industry.

Sporting organisations also resisted restrictions on tobacco advertising and sponsorship (with many of the same arguments now used in defence of gambling promotions).

But history shows us that legislated bans on tobacco advertising through sport made a huge difference to preventing young people from being exposed.

Read more: Gambling needs tobacco-like regulation in sports advertising and sponsorship

An opportunity for change

The Australian parliamentary inquiry into online gambling is looking at how to best respond to gambling marketing. It’s important we don’t follow the ineffective voluntary approach to marketing restrictions that the UK is taking.

As public pressure for action grows, we’re likely to see vested interests offering further minor concessions that have little impact on their advertising or their capacity to target young people.

We need strong action by governments, not small steps that lead nowhere. Gambling and sporting bodies should play no part in decisions about keeping young people and the community safe from this predatory industry.

And their predatory ads should be removed completely from the sporting arena, not just the front of matchday shirts in the English Premier League.

Samantha Thomas has received funding for gambling research from the Australian Research Council, Healthway, the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, and the NSW Office for Gambing. She is currently the Editor in Chief of Health Promotion International, an Oxford University Press Journal.

Dr Hannah Pitt has received funding for gambling research from the Australian Research Council, the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, the NSW Office for Responsible Gambling, VicHealth and Deakin University.

Dr Simone McCarthy has been employed on research projects that are funded by the Australian Research Council and the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.