A faraway cosmic explosion is evidence of a never-before-seen type of stellar death, a new study suggests.

A gamma-ray burst (GRB) detected in a distant galaxy nearly four years ago was likely generated by a demolition-derby-style collision between two stars or stellar remnants, according to the study.

"These new results show that stars can meet their demise in some of the densest regions of the universe, where they can be driven to collide," study lead author Andrew Levan, an astronomer with Radboud University in the Netherlands, said in a statement. "This is exciting for understanding how stars die and for answering other questions, such as what unexpected sources might create gravitational waves that we could detect on Earth."

Related: What is a gamma-ray burst?

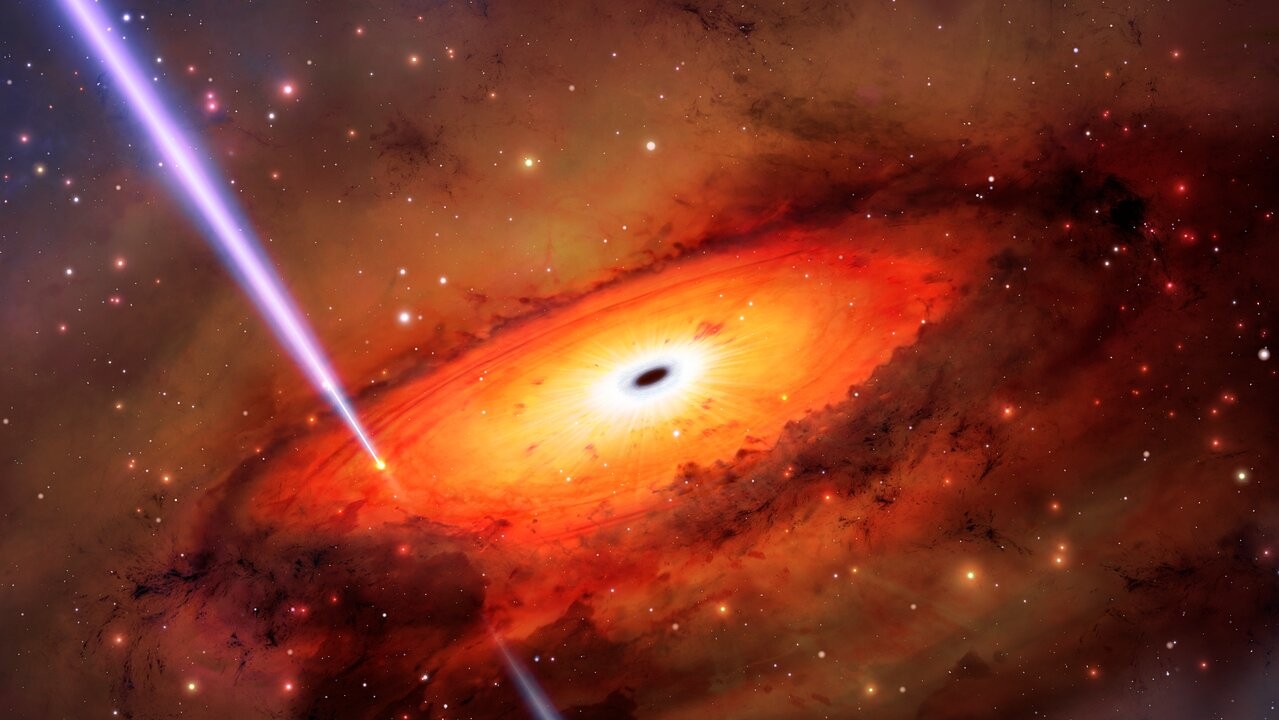

Gamma-ray bursts are the most powerful explosions in the universe, emitting in just a few seconds more energy than our sun will produce during its entire life.

There are two types of GRBs: short ones, which last for two seconds or less, and the long variety, which can go on for multiple minutes. Astronomers think short GRBs generally result from mergers between neutron stars, whereas long ones are usually spawned when stars at least 10 times more massive than the sun go boom in supernova explosions.

The newly analyzed burst, known as GRB 191019A, is a long one; it lasted a little more than a minute. It was first spotted by NASA's Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory in October 2019, in a galaxy that lies about 3.4 billion light-years from Earth.

Levan and his team studied GRB 191019A with the Gemini South telescope in Chile. These observations allowed the researchers to determine that the explosion occurred less than 100 light-years from the galaxy's center. And they saw no signs of a supernova in that area.

"Our follow-up observation told us that, rather than being a massive star collapsing, the burst was most likely caused by the merger of two compact objects," Levan said. "By pinpointing its location to the center of a previously identified ancient galaxy, we had the first tantalizing evidence of a new pathway for stars to meet their demise."

That new pathway is a random collision between two stars, or stellar remnants such as black holes or neutron stars (the superdense leftover cores of dead stars).

These objects are known to collide; for example, the LIGO project has detected gravitational waves generated by the spiraling together of black holes and neutron stars.

But these previously observed encounters are mergers between objects that once made up a binary pair. The hypothesized event behind GRB 191019A is something more random and chaotic — and there would be plenty of opportunity for such chaos near a galaxy's heart, according to the study team.

In such environments, a million or more stars could be zooming through an area just a few light-years wide, according to officials with the U.S. National Science Foundation's NOIRLab, which operates the International Gemini Observatory, of which the Gemini South scope is a part.

"Such extreme population density may be great enough that occasional stellar collisions can occur, especially under the titanic gravitational influence of a supermassive black hole, which would perturb the motions of stars and send them careening in random directions," NOIRLab officials wrote in the same statement.

"Eventually, these wayward stars would intersect and merge, triggering a titanic explosion that could be observed from vast cosmic distances," they added.

The research team wants to find and characterize more events like GRB 191019A — ideally pairing visible-light data with a corresponding gravitational-wave detection. Such "multimessenger" observations would reveal a great deal about these enigmatic explosions, team members said.

The new study was published online today (June 22) in the journal Nature Astronomy.