Having studied the social, political and economic history of 20th-century Britain it’s clear that much has changed, for example technology, political reform, and social and cultural movements. But I’ve also learned how much remains the same even after a century of progress, and how easily changes for the better can be reversed.

The turn of the century in 1900 is a good point to start because it was when major social inequalities became the prominent, urgent political issues they have remained ever since. The trade union movement was increasingly militant, challenging inequalities of income. The Labour party was founded, with a central mission to eliminate the disadvantages of working class people. And women demanded, with increasing determination, the vote and other legal rights and opportunities, partially gaining the vote in 1918.

Racism

Racism and anti-racism were prominent, particularly antisemitism directed at the thousands of Jewish refugees who fled persecution in Russia. They congregated in cities, especially in east London, and soon made substantial contributions to the economy. But then, as now, immigrants were accused of taking jobs and homes from British people, disrupting communities and culture, and reducing living standards.

This led to the first restrictions on immigration to the UK under the Aliens Act 1905. To remain, immigrants would have to show that they could support themselves and their dependants “decently”, and could “speak, read and write English reasonably well”. The Conservative prime minister, Arthur Balfour, told parliament at the time: “We have the right to keep out everybody who does not add to … the industrial, social and intellectual strength of the community” - which sounds familiar.

The Aliens Act did not apply to immigrants from the vast and still expanding British Empire, including those from the Caribbean, Africa and South or East Asia. People born within the empire had always been defined as citizens of the United Kingdom with full legal resident rights. This remained the case until 1962, although until the recent Windrush Scandal this had been generally forgotten including, evidently, by the Home Office.

But it is not novel for migrants from empire and the Commonwealth to suffer discrimination, including for lacking documentation when required. Even in the early 20th century between the wars, if they came to official notice, for example by claiming unemployment benefit, they could be expelled from the country if they could not prove their place of birth. This was often difficult for poor people who did not routinely have, and could not could easily afford, birth certificates.

Recent accusations of antisemitism suggest that racism has not diminished in the past century. Indeed restrictions on immigrants have increased since the 1960s and expressions and incidents of racist intolerance continue despite a succession of anti-discrimination laws since 1968.

The working poor

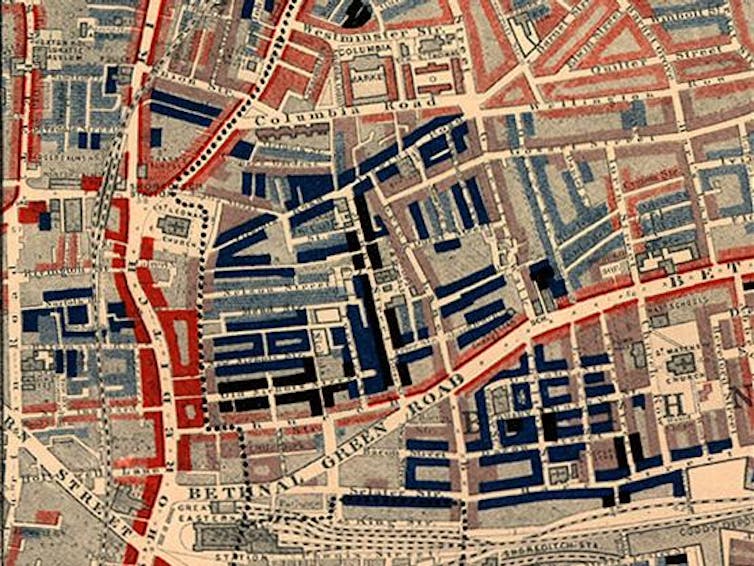

Awareness of the abject conditions in which the urban poor lived around 1900 was brought to light in pioneering works of fact and fiction: Arthur Morrison’s novel A Child of the Jago (1896), set in London’s East End, Jack London’s record of his time living in the same districts, People of the Abyss (1903), and the painstaking street-by-street surveys of Charles Booth in London and Seebohm Rowntree in York (1889–1903). These revealed alarming poverty, even among people in full-time work – not just the “idle layabouts” or “undeserving poor” of right-wing mythology.

Leo Chiozza Money, an Italian immigrant economist and Liberal politician, revealed in Riches and Poverty (1905) that income and wealth was concentrated in very few hands: two thirds of private wealth rested with 17,000 property holders out of a population of 44.4m, of whom 90% left no recorded property at death.

Demands for reform grew: the first steps of the modern welfare state, including the introduction of free school meals in 1906, old age pensions in 1908, and National Insurance in 1911.

What has really changed?

Gathering these findings into my new book, Divided Kingdom: A History of Britain, 1900 to the Present, I was shocked by the similarity between the level and causes of poverty at that time and now. Rowntree had found a quarter of people in the fairly typical city of York living in poverty, 52% of them in families with at least one full-time worker on inadequate pay. He defined poverty as having sufficient income for essentials of food, clothing, fuel, but no more.

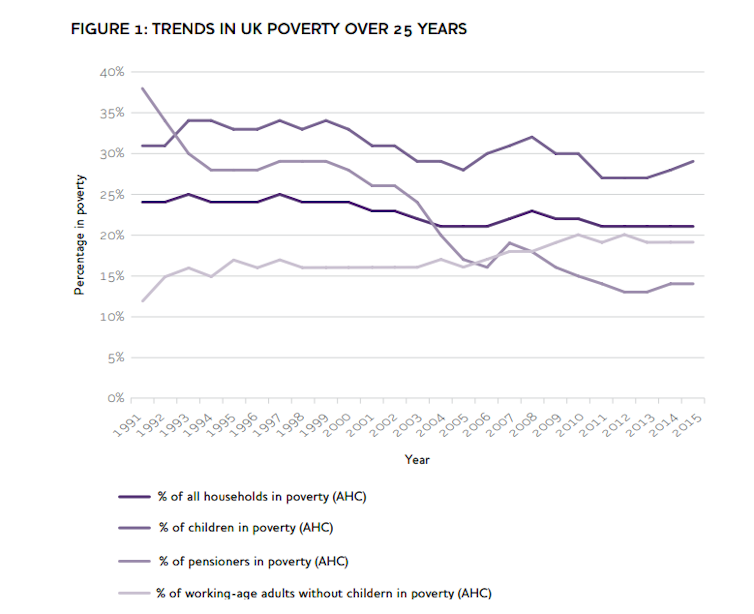

The Rowntree Foundation (created in his honour) has published surveys showing that in 2015-16, about 20% of the UK population lived in poverty, 60% in households including an inadequately paid full-time worker. The Resolution Foundation recently published similar figures for 2017-18, which showed that around 23% of the British population (excluding Northern Ireland) and 33% of children live in poverty.

Our society is much wealthier now than in 1900. The definition of poverty is less stringent, defined by the internationally agreed standard of income below 60% of national median income, since the life chances of those living so far below the average standards of modern society are severely restricted.

But these official figures exclude the large and growing numbers of homeless people living rough on the streets or in hostels – tens of thousands certainly, though exact figures are uncertain. And the growing use of food banks – unheard of in Britain until recently – should prompt us to ask how many people truly are living in absolute poverty comparable with the 1900s.

The welfare state led to improved living standards and the gradual reduction of wealth and income inequality, reaching its narrowest point in the 1970s when (in contrast to the denigration the decade so often receives) welfare services and benefits were also at their peak, and affordable council housing was still being built. But in part due to the erosion of the welfare state and the sale of council housing without being replaced, poverty and inequality have grown since 1979, although the shifts were more gradual under the New Labour governments of 1997-2010 than before or since. Today we see a return of the stigmatisation of supposed “shirkers” on benefits, despite many of them being in underpaid work.

Surveys that revealed poverty and inequality in the early 20th century brought the welfare state into being. A century later, similar levels of poverty with similar causes now follow its decline. After all the change and hope, and all the wealth generated in the 20th century, too often it was short-lived, and century-old problems remain or have now returned.

Pat Thane does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.