The pound dropped to a fresh 37-year low against the dollar as the chancellor unveiled tens of billions of pounds of tax cuts and spending.

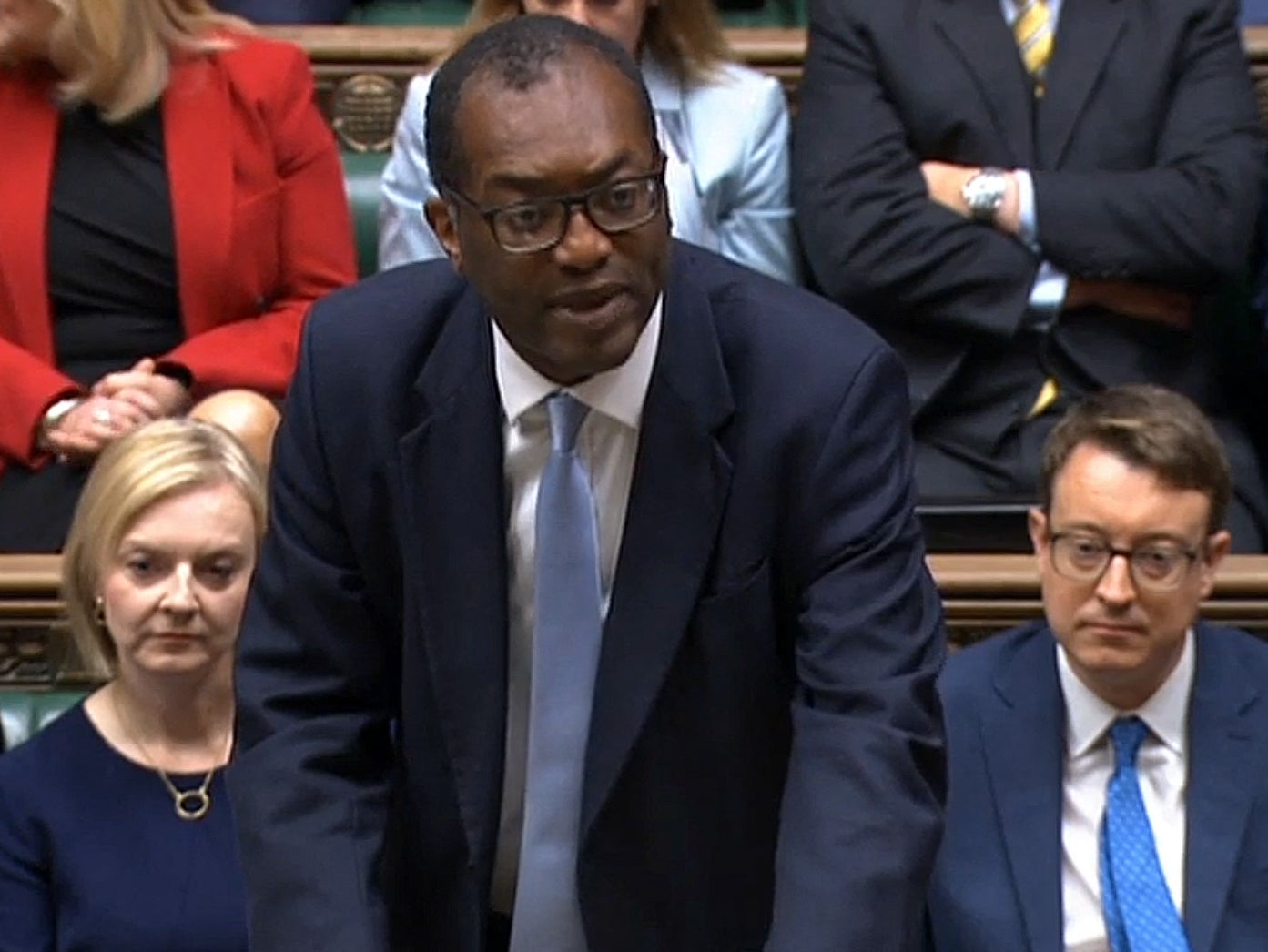

Sterling declined by 0.89 per cent to 1.115 US dollars as Kwasi Kwarteng outlined his “growth plan” for the UK economy on Friday morning.

It has since stabilised at about 1.119 dollars, but this remains below the previous 37-year low struck earlier this week after concerns over surging interest rates hit the currency.

It comes after the Bank of England launched another 0.5 percentage point interest rate hike to 2.25 per cent on Thursday and warned the UK could already be in a recession.

The central bank previously projected the economy would grow in the current financial quarter but said it now believes Gross Domestic Product (GDP) will fall by 0.1 per cent, meaning the economy would have seen two consecutive quarters of decline – the technical definition of a recession.

The chancellor, who was appointed on 6 September, set out his first “mini-Budget” at a time when the UK faces a cost-of-living crisis, recession, soaring inflation and climbing interest rates.

The 45p income tax rate paid by Britain’s highest earners will be axed, in the biggest surprise in Mr Kwarteng’s plan.

The chancellor also accelerated a planned 1p cut in the basic rate – from 20p to 19p – which will now come into force next April.

Mr Kwarteng claimed abolishing the 45p rate for people earning more than £150,000, already cut from 50p by George Osborne a decade ago, “will simplify the tax system and make Britain more competitive”.

The chancellor also confirmed he is axing the cap on bankers’ bonuses, while reversing the increase in National Insurance contributions which will also overwhelmingly benefit the wealthy, analysts say.

Mr Kwarteng said his economic vision would “turn the vicious cycle of stagnation into a virtuous cycle of growth”.

But shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves said the strategy amounts to an “admission of 12 years of economic failure” under successive Conservative governments.

By terming it a “fiscal event” rather than a full Budget, Mr Kwarteng avoided the immediate scrutiny and forecasts of the Office for Budget Responsibility.

Economists had warned the chancellor’s tax-cutting ambitions could put further pressure on the pound, which has also been impacted by strength in the US dollar.

Former Bank of England policy maker Martin Weale cautioned the new government’s economic plans would “end in tears” – with a run on the pound in an event similar to what was recorded in 1976.

Economists at ING also warned on Friday that the pound could fall further to 1.10 against the dollar amid difficulties in the gilt market.

Chris Turner, global head of markets at ING, said: “Typically looser fiscal and tighter monetary policy is a positive mix for a currency - if it can be confidently funded.

“Here is the rub - investors have doubts about the UK’s ability to fund this package, hence the gilt underperformance.

“With the Bank of England committed to reducing its gilt portfolio, the prospect of indigestion in the gilt market is a real one and one which should keep sterling vulnerable.”

Meanwhile, concerns over higher interest rates and pressure on consumer spending continued to weigh on the stock market.

The FTSE 100 fell by 1.48 per cent to 7,054.64 points in early trading – its lowest since mid-July.

According to a document published by the Treasury following Mr Kwarteng's statement, the plans set out by the chancellor will cost an eye-watering £161 million over five years.

The cost of the combined homes and business energy bills bailout alone comes to around £60bn in the first six months, with the government having to borrow most of the money to cover the cost.

This means Mr Kwarteng will be forced to turn to international markets. Governments borrow money by selling gilts, a sort of IOU, on international markets.

Anyone can buy them, such as through premium bonds, but most buyers are banks, pension funds and other big institutions. They are usually seen as a “safe” because the risk of them not being paid back is considered small.

As with most loans, the government promises to pay back what it has borrowed, plus interest - rates of which are rising across most of the West, including in the United States, where some of the world’s biggest lenders are based.

By borrowing more money the government is adding to the national debt which, according to the latest available figures, currently stands at £2.4tn.

Because interest rates are rising it is becoming more expensive for the government to borrow money, which will have to be paid back at some point in the future, probably through higher taxes.

In the aftermath of Mr Kwarteng's statement, the yield on benchmark UK 10-year bonds - which reflect government borrowing costs - rose sharply to 3.8 per cent.

Additional reporting by Press Association