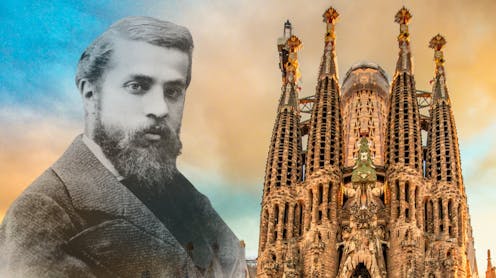

In one of his final announcements before his death, Pope Francis granted Catalonian architect Antoni Gaudí the title of “venerable”, due to his dedication to the design and build of the Sagrada Família church in Barcelona. This recognition is the second of four steps towards sainthood, a process that started more than three decades ago by a secular association founded in Barcelona in 1992 and led by local architects. If this happens, Gaudí would be the first secular architect in history to be declared a saint.

The Sagrada Família was originally devised by the religious book printer and seller José María Bocabella, who bought the site and founded an association to promote the construction. It was started in 1882, but in just one year the original architect Francisco de Paula del Villar y Lozano resigned due to creative differences with the association’s architectural adviser Joan Martorell.

After declining the job himself, Martorell fervently recommended his protégée Antoni Gaudí who at that time was only 31 years old. He took over and redesigned it entirely, transforming Villar’s predictable neo-gothic design into what the American architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock described as “the greatest ecclesiastical monument of the last hundred years”.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

From the moment of his appointment, Gaudí worked obsessively on the project. In 1915, once he finished the crypt of the Church of Colònia Güell, his other lifelong project, he devoted himself entirely to the Sagrada Família. He suddenly died in 1926, when he was hit by a tram just a few blocks from the church.

Gaudí was fully aware that he would never see the construction completed. Since its inception the construction was solely financed by donations, and its progress frequently slowed due to lack of funds.

The Sagrada Família is the largest unfinished Catholic church in the world, and it has become a living piece of architectural history, showcasing design methodologies, materials and tools spanning the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries.

Visionary techniques

Though Gaudí was a gifted draftsman, he rarely drew detailed plans as his design methods. Instead, he relied on close working relationships with builders and crafts people. He preferred scaled models and developed all sort of unique techniques to develop and communicate his designs to others.

Probably one of the most famous are his upside-down catenary curve models which he used to form-find the main structure of some of his buildings.

In this process, he traced the outline plan of the Sagrada Família on a wooden board at a tenth of the scale and placed it on the ceiling. Then, he tied cords from the points of the plan where the columns were located. Later, he hung small sachets filled with lead to represent the weight that the arches would have to support. Finally, he carefully measured and photographed the resulting model from many angles and turned the photos upside down so the strings hanging in pure tension would represent stone and concrete arches in pure compression.

The expertise required to construct these models was remarkable. In 1986, it was described in painstaking detail by professor of architecture Jos Tomlow at the Institute for Lightweight Structures under the supervision of the renowned architect and structural engineer Frei Otto.

Tomlow and Otto analysed the hanging design model for Gaudí’s unfinished church of the Colònia Güell, which took him nearly ten years to complete. The research team made a scaled replica of the model which was instrumental for understanding Gaudí’s empirical design methods and bringing a renewed interest to his unfinished masterpiece.

Completing the Sagrada Familia

By the end of the 1980s, the construction of the Sagrada Familia was suffering an impasse. The architects continuing the work, now in their nineties, had completed much of the work started together with Gaudí. But they did not have further models or plans to guide their development, as many of the original models, drawings and photographs were destroyed during the 1936 Civil War.

Fortunately, a younger generation of architects were able to analyse the existing design vocabulary and extend it to fill out the gaps using groundbreaking parametric design tools. Using parametric design, instead of simply reproducing digitally Gaudí’s existing geometries, endless new variations could be automatically generated by changing predefined variables.

During the 1990s, the same team introduced newer digital fabrication technologies such as 3D printing and robotic stone carving. These were instrumental to keep the construction of Gaudí’s impossible shapes under a reasonable budget and time-frame.

After several decades of long delays, the temple has experienced a substantial increase in visitors, which has boosted the construction efforts. The latest plans have set the completion for 2033 when it will become the tallest church building in the world. Just seven years after the 100th anniversary of Gaudí’s death, and probably in perfect timing for his canonisation.

Javi Buron Garcia does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.