In Germany, the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) won a district council election for the first time on Monday. Robert Sesselmann’s victory as district administrator – the equivalent of a mayor – in the Eastern town of Sonneberg comes only a day after Greece’s conservatives clinched an outright majority in the country’s parliamentary polls, topping left-wing parties Syriza and Pasok. Meanwhile, the Spanish left is also bracing for an early general election on 23 July, after losing to the Spanish conservative Partido Popular (PP) and far-right Vox parties in May.

Such developments might send a signal to European politicians to lean further to the right in a scramble to save votes. Yet our latest research, published this month, shows that politicians’ perceptions may not actually reflect voters’ true interests and opinions. Worse still: it appears to be an error that many other politicians have already made.

866 officials surveyed

In an influential 2018 study, David Broockman and Christopher Skovron showed that US politicians overestimated the share of citizens who held conservative views. On questions related to state intervention in the economy, gun control, immigration, or abortion, the majority of both Republicans and Democratic representatives surveyed believed that a greater share of citizens supported right-wing policies than what public-opinion data revealed.

We were curious whether conservative bias in politicians’ perceptions of public opinion was limited to American politics or was a broader phenomenon. To explore this, we interviewed 866 politicians in four democracies that whose political systems differ from each other and from that of the United States: Belgium, Canada, Germany and Switzerland. The politicians interviewed spanned the full political spectrum, including politicians from the radical right (Vlaams Belang, SVP/UDC), moderate centre-right (CDU/CSU, Conservative Party of Canada), centre-left parties (SPD, PS, SP.a-Vooruit) and radical left (PTB, Die Linke).

Participating officials, who included members of national and subnational (provinces, cantons, regions, Länders) legislative bodies, were asked to evaluate where general public opinion (but also that of their party voters) stood on a range of issues: pension age, redistribution, workers’ rights, euthanasia, child adoption by same-sex couples and immigration. We then compared their answers with public opinion data that we evaluated using large-scale representative surveys that we fielded in the four countries at the same time.

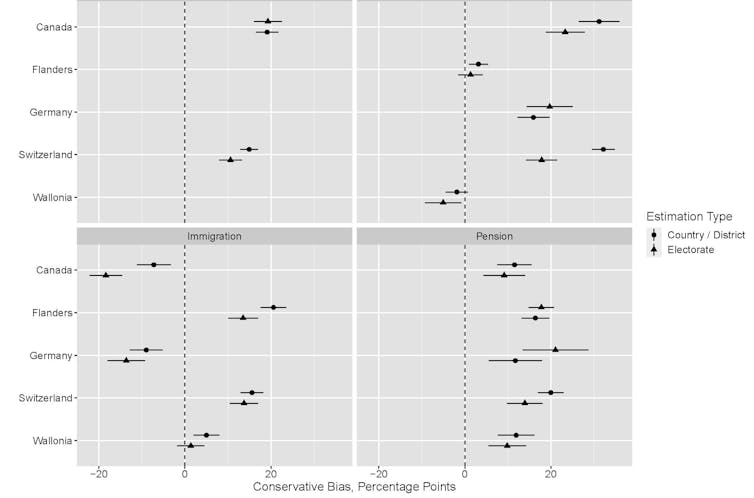

Our findings are clear and straightforward. In all four countries, and on a majority of issues, politicians consistently overestimate the share of citizens who hold right-wing views. Figure 1 reports the average gap between politicians’ perceptions of general public opinion and citizens’ actual opinions (circles), and the gap between their estimation of their party’s electorate opinion and the observed opinion within that electorate (triangles). These estimates are reported for each issue domain and each country we studied. Both measures reveal a substantial and largely consistent conservative bias in politicians’ perceptions – both for the overall public and party electorates. Importantly, politicians’ overestimation of how many citizens hold right-wing views is consistent across the ideological spectrum. Politicians hold a conservative bias regardless of whether they represent left- or right-wing parties.

While the overall pattern is remarkably stable, we also uncovered important variation across issue domains. For example, citizens are much less in favour of raising the pension age than politicians think. There were also differences between countries, such as a smaller conservative bias in Wallonia (Belgium). But the global picture is clear: the overwhelming majority of politicians we studied (81%) believe that the public holds more conservative views than is the case.

The only exception appears to be when politicians estimate public opinion on immigration-related policies. When asked about issues such as family reunion, asylum or border control, there is also a misperception of public opinion among politicians but not always in the conservative direction. Politicians in Belgium (both Flanders and Wallonia) and in Switzerland have a conservative bias on such issues, but in Canada and Germany, there is a large liberal bias in politicians’ perception of public opinion regarding immigration.

The result of lobbying?

The big question is why politicians perceive public opinion to be more right-wing than it truly is. One explanation provided by Broockman and Skovron for the United States was that right-wing activists are more visible and tend to contact their politicians more often, skewing representatives’ information environment to the right. We tested this explanation in our studied countries, but could not find evidence to support it. The right-wing citizens in our sample are not more politically active, and therefore visible, than their left-wing counterparts. Yet the idea that politicians’ information environment might be skewed to the right can find support in other work.

Earlier research has shown that politicians tend to receive disproportionally right-skewed information from business interest groups. Social media, which politicians use more and more, also tends to be dominated by conservative views, and as politicians spend more time online, and their news media diet is growingly filtered through social media feeds that create interactions and feedback skewed to the right, their views may be accordingly distorted. It has also been shown that politicians tend to pay more attention to the policy preferences of more affluent and educated citizens, and those citizens vote more often and hold more often right-wing views, at least on economic issues.

The observed conservative bias might also be associated with what social psychologist call “pluralistic ignorance” (i.e., misperceptions of others’ opinions). When it comes to liberals, for example, social psychologists have shown that they tend to exaggerate the uniqueness of their own opinion (“false uniqueness”. Conservatives, by contrast, perceive their opinions as more common than they are (“false consensus”). These processes could explain why we find a conservative bias found among both liberal and conservative politicians. Finally, recent election results such the Presidential elections in France, or the recent parliamentary elections in Greece and Finland, with the growth of the radical right and the victories of right-wing conservative parties, might also have sent a signal to politicians about the conservativeness of citizens that is not necessarily in step with their actual opinions.

A threat to representative democracy

Irrespective of the sources of the conservative bias, the fact that it is persistently present in a variety of different democratic systems has major implications for the well-functioning of representative democracy. Representative democracy builds upon the idea that elected politicians are responsive to citizens, meaning that they by and large attempt to promote policy initiatives that are in line with people’s preferences. If politicians’ ideas of what the public thinks – let alone their own party’s voters – are systematically biased toward one ideological side, then the political representation chain is weakened. Politicians may erroneously pursue right-wing policies that do not in fact have the popular support, and may refrain from working to advance (incorrectly perceived) progressive goals. But if citizens are less conservative than what politicians perceive them to be, the supply side of policy is at risk of being consistently suboptimal and may have broader, system-wide implications such as growing disaffection with democracy and democratic institutions.The recent social unrest in France regarding raising legal pension age might be an example of a policy debate in which governments perceive public opinion leaning more to the right than it actually is.

The situation is not without hope, however, and access to accurate information seems to play an important role. A 2020 study in Switzerland has shown that a sustained use of direct democracy might help politicians better understand public opinion. In the same logic, a recent study of US elected officials show that they tend to misperceive support for politically motivated violence among their supporters. But when exposed to reliable and accurate information, they update and correct their (mis) perceptions. Building on such studies, we believe that more work needs to be done both to understand the sources and prevalence of conservative bias, and to identify additional ways of offsetting it.

Jean-Benoit Pilet has received research grants from the European Research Council (ERC) and the Belgian National Fondation for Scientific Research (FNRS)

Lior Sheffer has received funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.