The energy sector wants the Government to urgently introduce regulations enabling carbon capture and storage in New Zealand, as a way to cut CO2 emissions. But as Nikki Mandow finds out, others have very different opinions.

Carbon capture and storage - pulling carbon dioxide out of industrial processes, energy production (and even the air) and injecting it deep into the ground – is a hot topic in international climate circles. The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, for example, sees CCS (as it’s known), as an essential part of an emissions reduction toolbox, but one that's under-delivering.

“Currently, global rates of CCS deployment are far below those in modelled pathways limiting global warming to 1.5°C to 2°C,” the March 2023 report says.

We need more CO2 captured and stored, and we need it happening significantly faster, is the message.

So calls from Energy Resources Aotearoa (the former Petroleum Exploration and Production Association of New Zealand) for our Government to move quickly to develop a regulatory regime to make CCS projects possible and bring them into the Emissions Trading Scheme, seem like a no-brainer.

Until you look at a bit of history, talk to environmental experts, and think about earthquakes.

Then it’s just a bit more complicated.

READ MORE: * Govt offers NZ Steel $30m more for bigger, faster emissions cuts * The crucial missing advice for the next emissions reduction plan

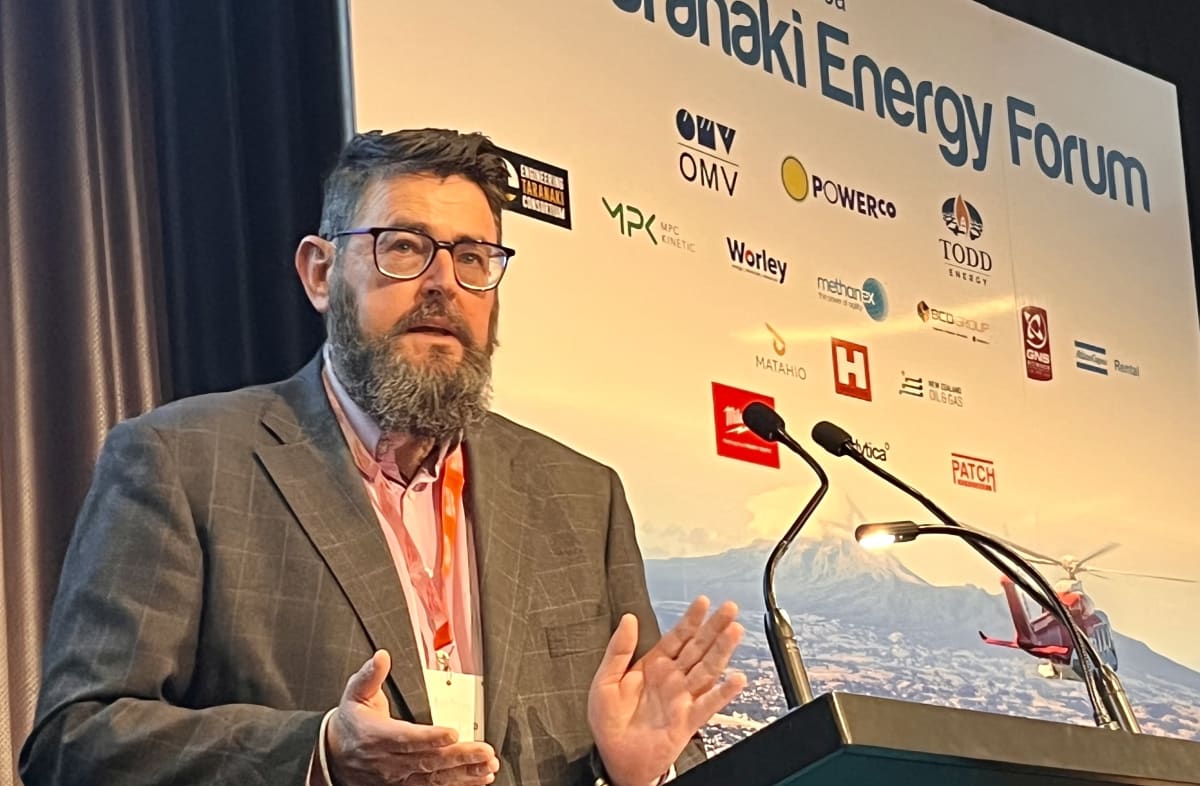

John Carnegie, Energy Resources chief executive, says New Zealand is “increasingly looking like a laggard” when it comes to carbon capture and storage.

“We don’t have a regulatory regime at all to enable CCS projects.. There’s a growing body of evidence that says ‘Hey, we need to get onto this'. There’s emerging technology and the sector needs a framework to allow the opportunity," he says.

“We’re about a decade too late.”

Energy Resources’ push for Government action follows recommendations from its ‘Vision for Gas 2035-2050’ report commissioned from energy consultants Castalia.

Castalia considered a variety of emissions reductions scenarios and concluded CCUS (carbon capture, utilisation and storage) would deliver the greatest emissions reduction for the least cost.

“CCUS should be rapidly investigated as an option to capture point source emissions from industrial, chemical, electricity generation, and process heat users of natural gas, as well as scope one emissions from upstream oil and natural gas producers,” the report says.

“Policymakers should focus on how investment in CCUS can be accelerated and ensure regulatory certainty enables investment. The sooner CCUS is available, the greater the emissions reduction benefits are realised.”

Carnegie says several Energy Resources members, which include the NZ subsidiaries of major international oil companies, are interested in government action on CCS, but a particular push has come from a new member, decarbonisation technology company 8Rivers.

“We’ve got investors lining up - my members and others - who are talking about getting interested in this,” he says. “Plus we have a number of other members who have depleted or depleting reservoirs that would be suitable for depositing residual carbon dioxide.”

The Castalia report found that “with a tail wind” carbon capture could be technically feasible in New Zealand in 2027.

“We need to make sure we capture the opportunity,” Carnegie says.

But does it work?

It’s here where the debate gets more complicated.

The claims around carbon capture and storage sound great, but as opponents point out, the technology has been deployed and trialled around the world for decades – including receiving billions of dollars of grants and subsidies from governments – but has produced little in terms of meaningful emissions cuts.

Australian Federal Resources Minister Madeleine King, speaking at the her country’s Petroleum Production and Exploration Association conference last week, might have called CCS the “single biggest opportunity for emissions reduction in the energy resources sector”, and said the technology could currently capture up to 44 million tonnes of CO2 a year. What she didn’t say was that the 44 million tonne capacity is just 0.12 percent of global emissions released by burning fossil fuels in 2021.

Just last week, oil giant Chevron announced its flagship Gorgon project in Western Australia, which has received $60 million in government funding but has been beset by problems since it started in 2016, is still running at only one-third of its capacity. And the situation is getting worse, not better.

The amount of CO2 being pumped into Gorgon's underground storage reservoir has dropped significantly over the past two years (from 2.7m tonnes in 2019-20 to 1.6m tonnes last year), at the same time as Gorgon’s emissions have shot up from 5.5m tonnes to 8.3m tonnes.

It’s not just Gorgon. Carbon projects – many linked with fossil fuel companies – have consistently over-promised and under-delivered.

New proposed standards from the US’s Environmental Protection Agency, an organisation which supports carbon capture, contain a critical edge.

CCUS technologies must be "done in a responsible manner that incorporates the input of communities and reflects the best available science,” the report says. “EPA will engage with communities and stakeholders... to ensure deployment of carbon capture and sequestration under the proposal is done in a responsible manner.”

“The EPA is calling the bluff on the power industry,” said Charles Harvey, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “There have been so many arguments that they’ve made in favor of CCS as a mature technology. … Now the EPA is saying ‘OK, you have to do it,’ and I don’t think they really can.”

“NZ: A shaky country”

Cindy Baxter is a NZ-based communications consultant who has worked on a range of environmental issues over the past 30 years, including carbon capture. She is scathing at the thought CCS could become a priority in NZ.

“It doesn’t work and the cost is astronomical,” she told Newsroom. “We would end up convincing the Government we could sequester carbon when we couldn’t, and we would pour money down a hole and end up with CO2 emissions still going into the atmosphere.

“We shouldn’t be looking into it.”

And then there are those pesky fault lines under Aotearoa.

“We are a shaky country. What happens if you bury millions of tonnes of CO2 underground and it comes out in an earthquake.”

In 2015, four geological and geotechnical experts from NZ and the UK released a paper entitled ‘Feasibility of storing carbon dioxide on a tectonically active margin: New Zealand’. While certainly not ruling out CCS, the scientists highlighted the risks not only of earthquakes impacting CO2 storage in NZ, but carbon capture and storage potentially triggering seismic activity.

“Some of these risk factors will also influence the relationship between social acceptance and the design of regulations,” the authors said.

“We are a shaky country. What happens if you bury millions of tonnes of CO2 underground and it comes out in an earthquake.” – Cindy Baxter, environmental consultant

Baxter doesn’t know of any research which has been done since that 2015 paper.

“We know so little about the viability of CCS in this country. We have put no money into the technical possibilities and we don't have the expertise, so how would you put together regulations around it? How would you work out how to oversee it and who would do that?”

There’s a commission for that

Dr Eric Crampton, chief economist at the New Zealand Initiative, doesn’t agree a good regulatory environment isn’t possible. Like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Crampton says we don’t have a choice. If we want to have a chance of holding the world to 1.5 degrees of warming, CCS has to be part of the mix.

He says it’s not just the traditional smokestack/fossil fuel production areas where carbon capture technology could potentially be exciting. Scientists around the world, including in New Zealand, are working on next-generation capture, including taking CO2 direct from the air.

Take Canterbury University’s Dr Allan Scott. Scott and his team are working on a CO2 sequestration process which starts with a common mineral called olivine. Olivine could potentially capture its own weight in CO2.

“I love the work that Allan Scott’s doing and if it works, it could plausibly scale enormously, so you want to have [CCS] in the Emissions Trading Scheme,” Frampton says.

Sure, there will be technical difficulties, including the earthquake risk, he says. But trees can burn down, and that doesn’t mean forestry shouldn’t be in the ETS.

“Some of the accounting is going to be difficult; some of the verification, auditing, and setting risk frameworks around it. But there’s so much potential in there.”

Moving onto Government’s radar

So, where is the Government on the issue of carbon capture and storage? Although it’s been off the radar for the past decade, that was not the case in the early 2010s, when there were two reports from MBIE, and analysis from the Productivity Commission. There was even a public-private sector organisation, the CCS Partnership, spearheaded largely by state-owned coal miner Solid Energy and its then chief executive Don Elder.

Still, back then, the result of months of investigation were inconclusive.

“Compared with other countries, New Zealand has relatively few point sources of CO2 emissions and a far higher renewable contribution to electricity generation,” MBIE’s 2011 report found. “New Zealand's international approach has been to support the uptake of CCS, in particular by countries that emit large amounts of CO2.

“[Our] support for the international development of CCS does not prejudge any decision on whether or when CCS might be undertaken in New Zealand.”

And that was more or less the end of it.

Twelve years on, what does the Government think of the push from Energy Resources and others for action on carbon capture?

Climate Change Minister James Shaw says the response will be different depending on whether the carbon capture involves taking out emissions direct from the air, or from industrial or energy processes.

“The government is exploring the role carbon capture from the air can play within a broader carbon removals strategy that will also look at New Zealand's mix of forestry and other nature-based carbon sequestration solutions,” Shaw tells Newsroom. “It does not currently have work underway on how we regulate carbon capture systems that capture and store CO2 directly from industrial fossil fuel or waste emissions.”

It’s a similar message from Energy and Resources Minister Megan Woods.

““Carbon capture, utilisation and storage is seen as a viable solution to reducing emissions in many places overseas. Mercury and Contact have recently launched trials capturing and reinjecting CO2 as part of their geothermal operations,” she says.

“More widely, there have been no decisions yet on how CCUS could best be used to help meet New Zealand’s climate change goals and a wide variety of solutions remain on the table. The Government will consult widely before making any legislative or regulatory decisions affecting the use of CCUS in New Zealand.”

“You don’t just throw the whole thing out because you don’t trust the industry.” – Eric Crampton, NZ Initiative

NZ Initiative’s Eric Crampton says he would like to see carbon capture in the ETS in the next 3-4 years.

And he doesn’t buy the argument often advanced by the environmental movement that carbon capture shouldn’t be considered because it’s simply a way for the fossil fuel industry to persuade governments and consumers to allow them to continue to operate for as long as possible.

We shouldn’t be naive that oil and gas companies don’t have agendas, Crampton argues. But that shouldn’t stop CCS being part of the mix.

“We should make sure the accounting is right. We should make sure any stored carbon stays in the ground, have somebody watching it, have meters and dials and sensors.

“That should be the job of the Climate Change Commission, making sure the credits are trustworthy and the accounting is sound and the monitoring mechanisms are there.

“You don’t just throw the whole thing out because you don’t trust the industry.”

“Dangerous distraction”

The problem, according to Wellington-based David Tong, a former lawyer, now senior campaigner in the energy transitions and futures team at Oil Change International, is carbon capture and storage has simply not delivered the sort of transformation of other technologies, either in terms of impact on emissions or cost reductions.

“Solar and wind have dropped in price radically over the last decade, but while CCS is technically possible at small scale, it does not appear to be cost-effective compared to just switching to renewables, in almost all cases.

Earlier this week, one of New Zealand’s biggest industrial emitters, New Zealand Steel, announced a $300 million upgrade of its Glenbrook mill, to replace two coal-fired blast furnaces with a single one powered by electricity. The Government will contribute $140 million to the project, which will remove 800,000 tonnes of emissions – 45 percent of NZ Steel's current emissions, 1 percent of NZ's annual emissions and 5.3 percent of the emissions cuts New Zealand needs to achieve under its 2026-2030 carbon budget.

By contrast, Tong calls developing regulations around carbon capture a “dangerous distraction” for government officials with limited resources grappling with the complexities of the Zero Carbon Act and emissions reduction plans.

“They can go to regulators and say, ‘No, no, we don't need to phase out oil and gas production. We can just phase out oil and gas emissions by using CCS." – David Tong, Oil Change International

“The problem is the attention CCS receives and the distraction it provides from doing what we need to do, which is rapidly and equitably transitioning off fossil fuels, the greatest cause of the climate crisis.

“Meanwhile, the fossil fuel industry or its enablers are able to project exponential growth in carbon capture and storage, that then allows them to go to their investors and say, ‘It's okay, we can keep digging for new oil and gas.’

“They can go to regulators and say, ‘No, no, we don't need to phase out oil and gas production. We can just phase out oil and gas emissions by using CCS. Even though the numbers for those CCS schemes don't stack up.

“It becomes a very effective lobbying and public relations tool and the way to create distorted results and modelling.”

A ‘hair shirt’ mentality

Crampton worries CCS has become tied up in an ideological debate between the value of gross versus net emissions reductions.

“The Government has been sending increasingly mixed signals, but I think more recently it has been wanting more focus on gross emissions.

“I don’t know that the climate cares about whether the next tonne of emissions that failed to be in the atmosphere is because someone failed to emit them in the first place, or because somebody sucked them out of the atmosphere directly. So long as you get to the same atmospheric concentration of carbon, it shouldn't matter how you get there.

“It almost feels like there’s this desire on the political side to wear a hair shirt around this, that it’s not real change unless we can feel the burn. It's like it’s cheating, like in their heads carbon capture and storage is somehow getting away from our obligation to reduce gross emissions.

“Even if it’s going to screw up our path to net zero.”