Polar bears have long held visual artists in their thrall. Over time, the mythologies around these extraordinary animals have evolved – and so have the ways artists have depicted them in their work.

Reflecting a deeply respectful even symbiotic relationship between human beings and the natural world, likenesses of polar bears crafted within Indigenous communities for thousands of years have long conveyed the awe-inspiring power of these mighty animals.

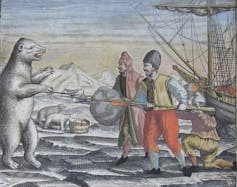

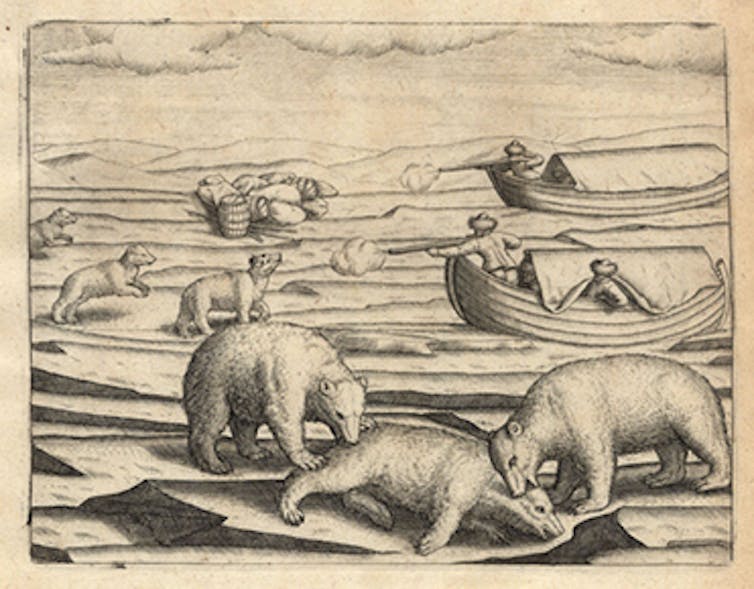

Towering above European adversaries in early 17th-century engravings, or bearing witness – alternately majestic and menacing – to whaling ships pictured in print and in paint, they testified to the expanding empires and commercial interests of western powers bent on exerting domination over new territories.

Conveying the bond of a resilient mother and her cub in a 21st century photograph, they hint at the fragility of a changing climate.

Though polar bears can hover at the edge of invisibility under the right conditions, they’ve left their indelible imprint upon the imaginations of image-makers from many eras and regions. Their shape-shifting significance in the context of western art intrigues me from my perch at Bowdoin College in Maine – whose mascot just happens to be the polar bear. As co-director of the college’s Museum of Art, I’ve helped expand our collection of polar bear pieces and have become fascinated by this animal’s enduring hold on audiences.

Exploration, empire and polar bears

Effigies and carvings created as long as 2,500 years ago in Paleo-Eskimo Indigenous communities reflect a sense of deep interconnection between the people and the bears, with cosmological and spiritual significance.

Westerners first encountered polar bears over a millennium ago, when Norse explorers advanced into the Arctic. In contrast to Indigenous representations of the bears, by the 15th century western artists were positioning human beings in opposition to these fearsome hunters as they adorned maps and explorers’ written narratives.

Even Shakespeare may leave a legacy of the fascination polar bears held for Elizabethan audiences. In one scene of “The Winter’s Tale,” a bear chases the character Antigonus from the stage. Historians have suggested that this dramatic exit may have been inspired by one of the live polar bears housed near the Globe Theatre, in London’s Paris Garden.

With the rise of European exploration and exploitation, the cultural legacy of the polar bear spread rapidly among European nations and their colonial outposts. The bears became identified with political and technological prowess, and a triumphant march toward the future. Groups of these giants are called “celebrations,” and their images in art tended to celebrate the brute forces of western modernity.

They appeared in the decorative arts, including a 19th-century silver Gorham ice bowl, ostensibly marking the U.S. acquisition of the territory of Alaska from the Russians in 1867. Fierce and menacing polar bears stand guard above the frozen treasure within the vessel, simultaneously celebrating North American success in the ice industry.

Prominent polar bear sculptures by Alexander Phimister Proctor at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago connected the United States with the distant north. Placed upon a pedestrian footbridge, the bear’s attitude – head up, powerful, taking its bearings as if to move forward – mirrored the optimism of the nation during the Gilded Age on the brink of the 20th century.

The polar bear also became a symbol of the conquest of the North Pole by American explorers in 1909. Despite controversy, Robert E. Peary was ultimately recognized for reaching it. Pants created from the fur of polar bears, which Peary described as “impervious to cold… almost indestructible,” helped make the feat possible. In the wake of this accomplishment, the polar bear became a popular college mascot — with Peary’s alma mater and my home institution, Bowdoin College, leading the way.

An icon transformed

But if the polar bear thrived into the mid-1900s as a sign of human might and of the successful mastery of antagonistic forces, this symbolic association evaporated in the latter 20th century. Today’s polar bears are more closely tied to the demise of the mythic western belief in conquest and domination.

The drawings of such pop artists as John Wesley and Andy Warhol mark this shift in perceptions.

In 1970, Wesley drew “Polar Bears,” depicting the intertwined bodies of polar bears seemingly enjoying a peaceful slumber. That same year, an international cohort of scientists published their conclusion that the bear stood a good chance of surviving extinction if people worked together to protect it.

Intriguingly, the artist’s cartoon-like renditions of the “great white bear” seems to echo the illustration included in the press release published by the U.S. Department of the Interior announcing this finding. But Wesley’s drawing raises questions about the fate of the motionless creatures it pictures: is this “celebration” in fact a tragedy?

Andy Warhol’s “Polar Bear” (1983) struts across the paper. Likely inspired by the 10th anniversary of the U.S. Endangered Species Act, the drawing points to the very fragility of the bear. Its composition uses the white of the paper to evoke the animal’s coat and its polar environment, suggesting the imminent possibility of their collapse into nonexistence. It would take another quarter century for the polar bear to be listed as threatened, in 2008.

By the early 21st century, pictures of the animal, such as on a seemingly diminishing ice floe, frequently associated it with catastrophic climate change and the endangerment of the species itself, as the art historian Nicholas Mirzoeff has noted.

Despite, or perhaps because of, their association with extinction, the allure of the polar bear seems only to have intensified. One curious reflection of this celebrity comes in the form of endearing anthropomorphic depictions of these wild creatures pitching consumer products like Coca-Cola.

But what are the implications of conflating the polar bear with human beings today?

The question has particular resonance as people reflect upon the fragility of our own species in the midst of a global pandemic that has already cost millions of lives.

Contemplating new strategies to promote healing – including science and social and political policies – perhaps there is something yet to learn from these exceptionally adaptable creatures, at home on solid ground and in the water. As people examine the broader implications of this current human crisis, and consider a lasting commitment to promoting global health, might there be room to hope that the polar bear might eventually become a new icon, this time of resiliency and recovery?

On the occasion of the 10th International Polar Bear Day, I’ll be thinking about what the enduring and ever-evolving sway of this magnetic mammal might mean to future artists.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]

Anne Collins Goodyear does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.