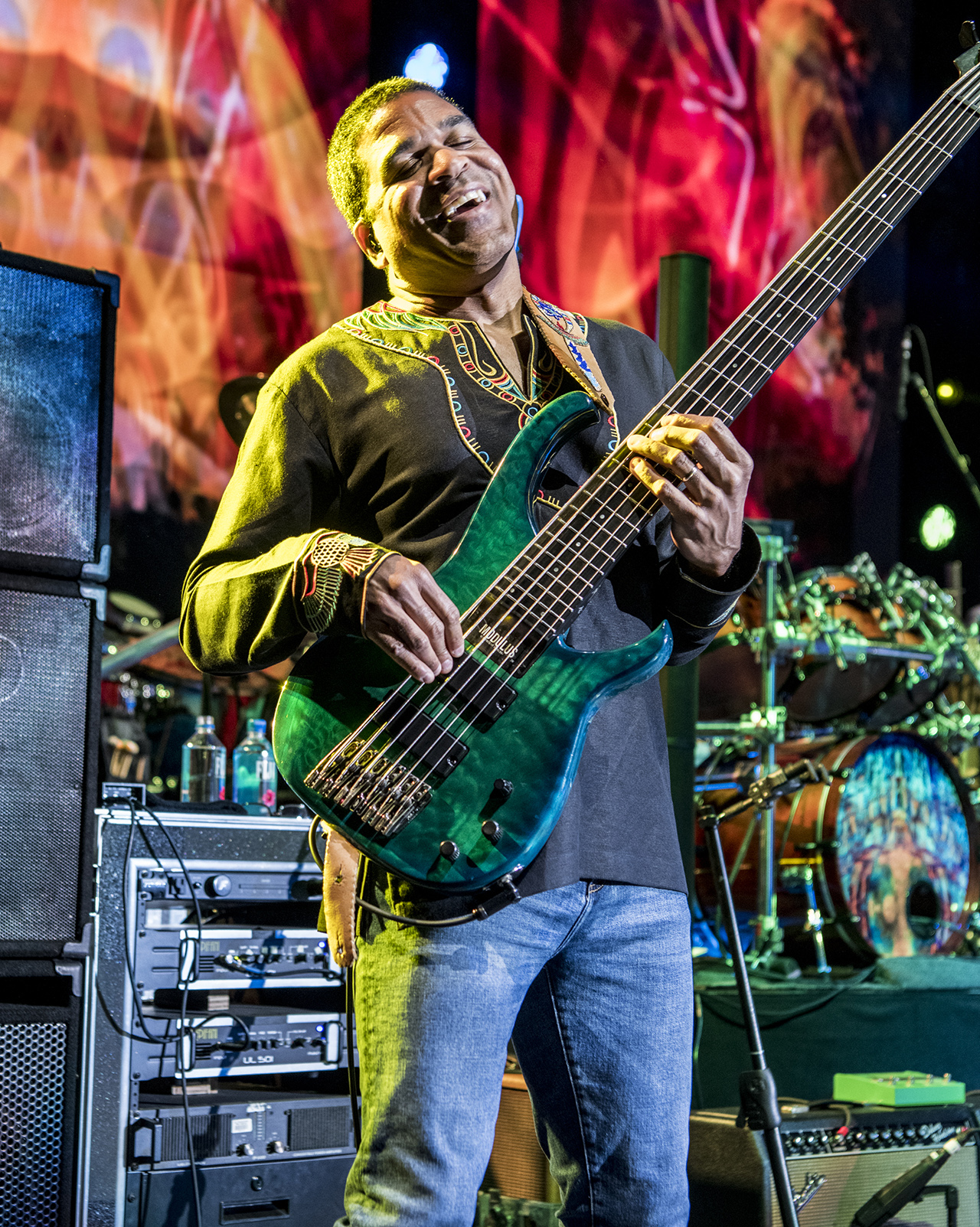

Few can hold down the low end with the versatile mastery of Oteil Burbridge. With origins in the musically rich city of Washington, D.C., and having played alongside Victor Wooten, Derek Trucks, Bob Weir, and more, Burbridge is a premier player. And he’s not only a master of four-string bass – he swiftly alternates between five and six strings.

You'd think there would be heaped doses of technical wizardry afoot. But no: like the greatest who influenced him, Burbridge pulls primarily from his soul.

“I prefer anything with honest feelings and intention,” he tells Bass Player. “My attention is held more firmly if things are rhythmically interesting too.

“That means: If you can find the groove! I’m seeking to reflect that in my music, and my life in general. I want to be more in tune and more in the groove onstage and off!”

During a break from the road Burbridge dialed in with Bass Player to dig into his gear, approach, and varied stops along the way.

You're known for using four, five, and six-string basses. What specific gear has most defined your career?

“All my basses have had that core, even if they were five or six strings. The green Modulus Quantum 6 I used on the first ARU [Aquarium Rescue Unit] record is the one I made my name on.

“I had many different Modulus basses over the years, including a signature bass called the OB-1, a semi-hollow body. I later got a couple of Fodera six-strings that were completely handmade.

“Recently, Joe Perman of Modulus Guitars built me a cool-looking six-string shaped like an Egyptian ankh. And most recently I’ve been playing a Sandberg California six-string bass. It’s only 7.5lbs and sounds amazing. I have a bad back so I needed something lighter, or else I would have to start sitting down all the time.”

What are the most significant differences in playing four, five, and six-string bass?

“It’s all about personal preference. The four-string is the most traditional, and the six is the most fun! I only play my six-strings these days. But then again, I also play my banjo bass, which is a four-string, so I guess I can’t say that.

“My regular banjo is a five-string, so I think it doesn’t matter. You must do whatever inspires you the most. I like to play chords on bass, and I like going lower and higher than I used to on four-string.”

What inspired you to incorporate scat-singing into your improvised bass solos?

“That was something Bruce Hampton was the catalyst for. We were always throwing different things at the wall to see what stuck. I hate my voice, but it stuck.

“One of his big principles was embracing the ‘mirror of embarrassment.’ It was the name of our second album. We were throwing all the rules into a blender. I still can’t believe we got a record deal doing that!”

Did growing up in the Washington, D.C., area impact you much?

“Parts of D.C. were beautiful. All the museums were free and easily accessible back then. It may be the same now. There was a lot of culture there. But D.C. is a political town.

“Honestly, I do not miss it in the slightest. I didn’t realize how much Gogo had gotten deep into my soul until I started writing music later, and that beat kept coming up.

“It was ubiquitous in D.C. where bands like Trouble Funk, Experience Unlimited, Chuck Brown, and the Soul Searchers could always be heard. I still love that style. There were also a lot of great jazz musicians there, but New York is really the place for that.”

What led to your joining the Allman Brothers Band in 1997?

Playing with Victor Wooten was easier because of the six-string bass. I can go lower and higher than a four-string, so staying out of the way is easy.

“Warren Haynes and Allen Woody quit, so the spots opened. It was basic. Trying to find your way in music that’s been around for such a long time is always difficult. I was five when the Allman Brothers Band started and one years old when the Grateful Dead started.

“Both bands are rooted in improv, and lots of the tunes are from the black American traditions. R&B, jazz, funk, and gospel are all things I was already used to. After a while you settle in. It just takes time.”

You also worked with Victor Wooten in 1997. How did you approach that?

“It was easier because of the six-string bass. I can go lower and higher than a four-string, so staying out of the way is easy. Vic and I come from similar musical backgrounds, so that part was easy.

“It wasn’t that hard – he’s so creative and adventurous that it’s always as much fun as a challenge. But I quickly learned that you should go first when it comes to soloing, unless it’s a ballad!”

What was it like working with Derek and Susan in the Tedeschi Trucks Band?

“It was awesome. I had hoped they would join forces for some time, but it was difficult for them because they both had good bands. I can’t imagine how hard it was to break up two good bands.

“Playing with my brother again every night after 11 years of being in separate bands was also great. Those three years were incredible. But I wanted to be home a lot more since I wanted to have kids.

“Being on the road all the time just wasn’t what I wanted to do anymore. I'm grateful for that time; we made some history. We won a Grammy after that first album. It was a trip to the Grammys for the first time and returning with two. We also got a lifetime achievement Grammy with the Allman Brothers Band that year. It was very surreal.”

Can you recount your sessions with Dave Grohl and Zach Brown in 2013 for The Grohl Sessions Vol. 1?

Zac was a trip and so was Dave Grohl. It was an unlikely cast of characters, for sure. But that’s how my life has always gone

“That was 11 years ago? Time flies! Their drummer, Chris Fryar, used to play in my band, the Peacemakers. He called me up and asked if I’d be into it. I said, ‘Hell, yeah!’ I had played country and bluegrass in Georgia, so it was familiar.

“Zac was a trip and so was Dave Grohl. It was an unlikely cast of characters, for sure. But that’s how my life has always gone. It was almost expected after playing with Col. Bruce Hampton. It was a lot of fun.

“We played the CMA awards together that year. I had lived in Nashville in the late ‘80s, so it was nice to go back and see some of the old spots I used to hang out at. It was a very short timewise, but memorable and fun.

“Dave is a great storyteller. He was never into heroin, so I’m glad he didn’t have to ever have that monkey on his back and lived to tell the tale.”

How did you end up joining Dead & Company?

“After Grateful Dead 50, Bob Weir, Billy Kreustzmann and Mickey Hart just weren’t ready to retire. It was a long shot, but it worked. You never know how people will respond. You must step into the ring and start throwing punches.

“Life is a gamble… After our first gig in Albany, I sure was relieved that people dug it. Going into M.S.G. the night after could have sucked if people didn't dig it! What an amazing eight years it's been. I never could have seen that one coming.

Col. Bruce Hampton gave me the missing pieces I needed for both the Allman Brothers and the Dead. I needed to be able to do those gigs authentically.

“I’m grateful I had that time with Col. Bruce because he gave me the missing pieces of delta blues, bluegrass, gospel and outer space music that I needed for both the Allman Brothers Band and the Dead.

“I needed to be able to do those gigs authentically. I needed to be marinated in the Deep South for a while. My dad had turned me onto all that when I was a kid, but I did those gigs when I moved down South.”

What genre do you most identify with?

“I hope to expand the boundaries of my identity. I naturally tend towards Black American music because that’s what I grew up with, but I have always been into other styles of music from all over the globe.

“My dad was really into European classical, Indian classical and African music of different kinds. I most identify with human music now. However, I’m extremely curious to hear extraterrestrial music, too. I might end up identifying with that strongly as well!”

- Burbridge’s most recent album, A Lovely View of Heaven – a tribute to the music of Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter – is out now.