Out of sight, out of mind.

That's one of the problems scientists face in their efforts to conserve the platypus.

Dr Gilad Bino, a platypus researcher of the University of NSW, said platypuses are vulnerable to human-related activities and "there's a long list".

"My opinion is there are definitely declines."

In seeking to protect the platypus, the science and conservation communities are trying to avoid discovering in 10 or 20 years that platypuses are in big trouble, like the situation with the koala.

They're concerned about the platypus facing what they call "local extinction" - a loss of the creature in particular geographic areas.

UNSW scientists recommended in 2020 that the platypus be listed as a threatened species under federal and NSW environmental legislation.

"The threatened species scientific committee found there wasn't enough data to support the nomination and it could review the matter as more information comes to light," Dr Bino said.

"We ended up in a bit of a catch-22. It's not on anyone's priority list at the state or federal level."

This means a lack of monitoring is occurring.

"To meet the threatened status criteria, we have to show a decline of greater than 30 per cent in either distribution and numbers over the past 20 years.

"What we do know is what we are doing to our environment and rivers is definitely having an impact on freshwater species, including platypuses."

In the Hunter, sedimentation that chokes rivers and destroys habitat is a threat to the platypus.

"Then you get cattle that trample banks. Platypuses are really vulnerable, obviously, to rivers drying up. In regulated rivers, it's a big issue if a lot of water is being taken at unsustainable levels. We need to make sure there are environmental flows that can sustain platypuses.

"At the peak of the drought in 2019, we were getting a lot of calls about stranded platypuses and rivers drying out."

As the climate changes, more extreme events are expected to further threaten platypuses.

"Droughts and floods that have a long sequence can really push populations beyond tipping points. Say you have a massive drought and then a bushfire, a local platypus population might go extinct.

"Because there is no capacity for platypuses to recolonise that area from other areas, then we'll see these populations that just disappear.

"I'm not being an alarmist. I don't think platypuses are headed for extinction in the near future. But in some areas, local extinctions are possible."

Fragmentation of the environment with dams, weirs and roads also threaten the freshwater species, which live in burrows that they build in the banks of creeks, rivers and ponds.

Australian Platypus Conservancy biologist Geoff Williams said opera-house traps remained a problem for platypuses.

"They've been banned in NSW for over a year. That's been a good thing," Mr Williams said.

"But I suspect there are still many thousands of these things knocking around in people's garages. The message hasn't totally got through yet.

"Consequently, I think there's still a fair proportion of the population who just don't know the rules. NSW Fisheries are doing the best they can to try to get more publicity out, putting up signage in certain places. It will take a while for the message to get around."

Although it's illegal to use them in NSW, the traps are still being sold - including in the Hunter. Mr Williams said it was "ridiculous that any retailer is selling these items".

"There's a perfectly safe alternative that catches yabbies just as effectively - open-top nets. Tests have proven they catch just as many yabbies, but are safe for platypus and other species."

The platypus - along with the echidna - are the only mammals on the planet that lay eggs. They are considered one of the world's most unique animals, unlike any other on the planet.

WWF-Australia has described the platypus as "facing a silent extinction".

The organisation's rewilding program manager Rob Brewster is leading a three-year project to restore platypuses in the Royal National Park near Sydney.

"Rewilding as a philosophy is starting to get a lot of traction. It's moving beyond a status quo and offering people a brighter future for ecosystems and the potential to make things more biodiverse, rather than just conserving what's there now," Mr Brewster said.

"This isn't something we're just doing in remote areas. People see the benefits of living closer to nature and having nature in our cities."

He said rewilding programs involve significant plans into the opportunities and risks involved when "moving animals around".

"We look at the threats in the landscape and how we can best manage those to make sure we have every chance of success."

Platypuses have been extinct from the wild on mainland South Australia since the mid-1970s. Mr Brewster said there were discussions about a reintroduction of platypuses to the Torrens River in that state.

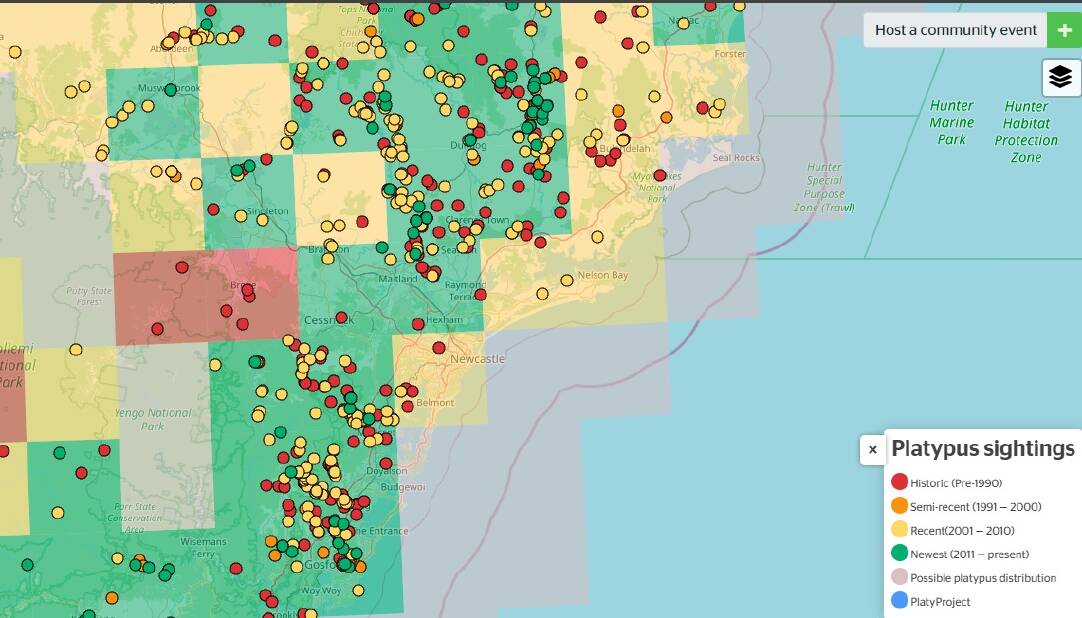

Platypus researchers at the UNSW and the Australian Conservation Foundation have established the platy-project map to help fill gaps in platypus data.

The project urges people to try to spot a platypus at a local creek or river and record what they see.

Relatively little is known about the species' past and present distribution and numbers. This limits accurate evaluation of conservation status and future population trajectories, a UNSW research paper titled, The platypus: evolutionary history, biology and an uncertain future, stated.

"There are massive gaps in our understanding of where platypuses occur," Dr Gilad said.

"We still have platypuses in our rivers. We can care for and appreciate them. We can do better and can protect land around rivers.

"Irrespective of political opinions, we can care about our environment - even just for our wellbeing."

A sequence of extreme events, such as bushfire, drought and flood, can worsen the predicament for platypuses.

"So if you have a healthy river and a bushfire goes through, platypuses are probably fine. But if the river is already degraded, all the trees are cut down, it's shallow because of sedimentation and there's patched habitat, a drought and then a bushfire, the platypuses there will probably be more vulnerable. I've seen that on the NSW Mid-North Coast and Kangaroo Island."

Mr Williams, of the platypus conservancy, said "the population status of platypus in most areas of NSW is of concern".

"That's why incidents of platypus being killed in nets can make a big hole in populations. We are concerned about their long-term future, so anything that causes further problems is something we need to jump on and address. The two big human-related issues are use of traps and litter getting into the rivers. Platypus are particularly vulnerable to discarded bits of fishing line and plastic rings, like six-pack holders. Work is being done to get our rivers back in better shape, so we hope things are improving."