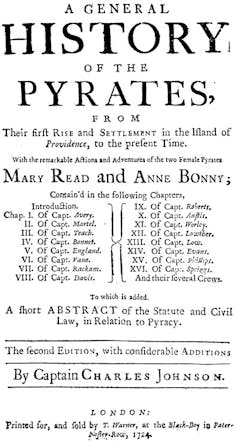

Three hundred years ago, A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates by Captain Charles Johnson first hit the shelves of London’s booksellers. The book aimed, according to Johnson, to give “a distinct Relation of every Pyrate who has made any Figure”.

Here were all the fabled plunderers of the seas: Blackbeard, Bartholomew Roberts, Anne Bonny and Mary Read and many others. More than any other book, the General History changed the way we see pirates. It created the image that word still conjures today.

The first edition appeared on May 14 1724 (in the Julian calendar; May 27 in the calendar we use now). It was sold by Charles Rivington at the Bible and Crown in St Paul’s Churchyard, London, a popular location for booksellers. James Lacy at the Ship near Temple Gate and J. Stone near the Crown coffee house also stocked it.

As I discuss in my new book, Enemies of All: The Rise and Fall of the Pirates, Johnson’s history was an immediate sensation. A second edition, “with considerable additions”, was rushed out the same year, after its forerunner’s “success by the Publick occasioned a very earnest Demand”.

In the second edition, Johnson promised a sequel “if the Publick gives him Encouragement” – and the public must have done just that. Johnson’s additional volume was published a few years later, by 1728. Translations and abridged versions soon followed.

The General History appeared in the waning years of what historians sometimes call the “golden age of piracy”. Though the meaning of that term varies, it is generally applied to the 1710s and 1720s. Blackbeard, or Edward Teach, died only six years before the General History appeared, in 1718; Bonny and Read were put on trial in 1720. The US historian Marcus Rediker estimates that some 5,000 pirates roamed the Atlantic and Indian oceans in these decades.

Yet, the success of the General History was not only due to its topicality. It is a gripping, vivid read.

It is full of characterful descriptions and dramatic action, as well as some horrifyingly graphic details. Teach is described as a man of “uncommon Boldness and personal Courage”, known for his “Frolicks of Wickedness”. His “Cognomen of Black-beard” derived, Johnson writes, from the “large Quantity of Hair, which like a frightful Meteor, covered his whole Face and frightened America more than any Comet … Imagination cannot form an Idea of a Fury, from Hell, to look more frightful.”

Johnson provides so many of the ideas now associated with piracy. He defines the “Jolly Roger” as the name commonly given to the stereotypical black flag of a pirate. He describes a scene that features something like walking the plank (albeit in a chapter on Roman pirates).

Another key feature he presents is various pirate codes, of which Roberts’ is the most well-known. Johnson claims it stated that “Every Man has a Vote in Affairs of Moment”, as well as “equal Title” – or right – to alcohol and provisions. Pirates form part of a commonwealth or fraternity, to use Johnson’s terms, as “Confederates and Brethren in Iniquity”.

Bonny and Read appear prominently too. These are the only pirates who were not captains who Johnson names on the title page, and who get chapters and illustrations of their own. As Sally O'Driscoll has shown, these pictures became increasingly sexualised in later editions. Bonny and Read’s story involved cross-dressing and the hint of a lesbian love affair – yet many details of it were considerably embellished or, more likely, made up.

That is the problem with the General History. Authors and artists – from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island to those behind the Pirates of the Caribbean movie franchise, the Netflix drama Black Sails, Our Flag Means Death on HBO and the Playstation game Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag – have gone back to it again and again. So too have academic historians, mining its colourful tales. Yet it remains a puzzle.

It mixes together fanciful invention with accurate accounts taken from contemporary newspapers and court records. One of its more famous characters is Captain Misson, a French rover associated with the utopian pirate settlement of Libertalia, who never existed – and nor did Libertalia.

The book’s authorship, and the true identity of Captain Charles Johnson, is also a mystery. In the 1930s, a literary scholar suggested Johnson was in fact Daniel Defoe. Many websites and libraries still list the book under Defoe’s name, though most scholars now disagree with the attribution.

A more likely candidate, according to historian Arne Bialuschewski, is a Jacobite controversialist by the name of Nathaniel Mist.

Mist worked with Defoe at times and got into trouble with the law for his forthright opinions about the Georgian monarchy. His Weekly Journal published the first two (very positive) reviews of the General History. You have to wonder at that coincidence.

If Mist was the author, it would explain the purpose of the General History as not a historical account of piracy but rather, as literature scholar Richard Frohock points out, a satire on British politics.

In the General History, the supposedly democratic pirates are pilloried, their democracies regularly collapsing into violent chaos. Its real target was people like the directors of the South Sea Company who, the author claims, were even worse than pirates. One review in the Weekly Journal suggested that each pirate was an allegory of some prominent public figure. Sadly, it didn’t identify any.

The tradition of using pirates as political rhetoric to get at opponents was nothing new. It dates back at least to Roman times and Cicero, if not earlier.

Yet the General History pursued that tactic in such a way that it has captured imaginations ever since. There is a deep irony in the fact that its author’s original purpose has been forgotten, while the very particular image of pirates he concocted has survived and thrived.

Richard Blakemore does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.