In January 2000, a young Stanford University student named Paul Martin walked into the office of a fledgling tech company called Confinity on University Avenue in Palo Alto. He was there to see Peter Thiel about an internship.

Thiel, who had yet to become a renowned founder and investor, was already a familiar face, thanks to the dinners he had hosted for staff of the Stanford Review, a conservative student newspaper on Stanford’s campus that Thiel had cofounded as an undergraduate studying philosophy. Martin, a business manager for that paper, had been struck by one dinner in particular at a steak house in Palo Alto, where he recalls Thiel discussing how China would become a substantial threat to the future of American interests, as part of a wider discussion ranging from religion to politics, economics to entertainment.

“He’s just—he’s an impressive person,” Martin says. “And so if he says, ‘Hey, I’ve got this company, and I think that this has a real shot at being a huge success,’ then you’re going to [think], ‘I should probably get on board with that.’”

When Martin arrived at Confinity, he was surprised to see another Review staffer already working there: Eric Jackson, who had been editor-in-chief during Martin’s freshman year. Jackson took the undergrad out to lunch after his meeting with Thiel—to a little spot down the street on University Avenue. “He [said], ‘You know, this is taking off. This is going somewhere. And if you come now, then you’re going to be a part of something special. If you wait, this might be over,’” Martin recalls.

Martin dropped out of Stanford—and off the university’s track team—shortly after to start working full-time at Confinity. That company would eventually undergo a name change—to PayPal.

Martin and Jackson were just two of dozens of individuals who have followed Peter Thiel on what has quietly become one of the surest paths to an enviable job in Silicon Valley. It all starts at the Stanford Review, the student newspaper Thiel founded with Norman Book, another future early PayPal employee, in 1987.

“We obviously didn’t envision it becoming this incredible tech Silicon Valley network decades later when we started back in 1987,” says Thiel, who agreed to sit down for an interview with Fortune to discuss the paper. (Joining Thiel on the call was Sam Wolfe, a former editor-in-chief from 2018–19 who met Thiel via the Review and now works for him as a researcher at his hedge fund.)

“We certainly were not ideologically monolithic in any way,” Thiel said in the interview. “But the fact that there were a lot of strong personal connections that, not only I had with people, but they had with one another—gave it a certain esprit de corps that helped a lot…[PayPal] certainly had a lot of volatility, a lot of ups and downs—and that kind of intense camaraderie was what was super helpful to get through the boom and the bust.”

On campus, the conservative student newspaper has gained a reputation over its more than 30-year history for riling up the left-leaning Stanford community. And every once in a while, one of its impassioned and controversial opinion pieces criticizing political correctness, lambasting homosexuality, or calling out one of Stanford’s professors, has trickled into the national headlines. So did a lawsuit that was filed by Stanford students including some Review writers against the college in the ’90s, which ultimately compelled the university to overturn its speech code meant to put a stop to bigoted speech on campus. But beyond a handful of high-profile exceptions, the paper has largely remained unknown beyond Stanford’s elite campus, even if its network has grown large.

Former Review editors say that Thiel has been influential in cultivating the paper’s community, well after Thiel received his undergraduate degree from Stanford in 1989. And Thiel remains involved to this day, hosting dinners for staffers for more than three decades now—at his home, or at places like the Sundance steak house in Palo Alto—where he discusses world events and political philosophy and asks students questions about college life and what ideas are circulating around campus. In 2017, there was a 30th anniversary party for Review alumni, and the Stanford Review’s current editor-in-chief, Walker Stewart, told Fortune he had attended a dinner for Review writers hosted by Thiel in just the past year.

A look back through the archived mastheads of the Review shows how vast—but also how tight—the legendary investor’s orbit is. Several of PayPal’s cofounders or early executives—Thiel, Craft Ventures’ David Sacks, and former U.S. ambassador to Sweden Ken Howery—wrote for the paper, as did three founders of Palantir, a defense technology company with a market capitalization of nearly $33 billion as of mid-August. You can add Founders Fund investor Keith Rabois, who had stints at LinkedIn and Square, and Founders Fund principal John Luttig to the mix as well. Joe Lonsdale, who worked for Thiel after serving as editor-in-chief of the Review and now runs venture capital firm 8VC, has hired a number of the conservative paper’s staffers, including Alex Moore, one of Lonsdale’s longest-running investing partners, and, just last year, recent Stanford alum Maxwell Meyer. (Lonsdale married another Review editor, Tayler Cox, and Lonsdale’s brother wrote for the paper, too.)

Thiel himself, who served on former President Donald Trump’s transition committee, is estimated to be worth some $9.3 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. Collectively—across venture capital funds and tech companies—this group of alumni has control over multiples of that. Founders Fund last reported $11 billion in assets under management. Lonsdale’s 8VC oversees more than $6 billion in committed capital. Not to mention Review alums who have gone on to wield influence at tech companies across the industry, such as Facebook (now Meta), where former Review business manager Gideon Yu was CFO for two years, or OpenAI, where Review alum Bob McGrew currently serves as vice president of research.

Six years ago, former Stanford student Andrew Granato spent almost a year poring through the Review’s vast network for an article in student magazine Stanford Politics—pinpointing nearly 300 Review alumni who had either worked for, or had received investments from, either Thiel or Lonsdale. And since 2018, those numbers have continued to rise. Fortune identified at least six more individuals who have gone on to intern or work at Palantir, Thiel Capital, Founders Fund, the Thiel Foundation, or Lonsdale’s venture capital fund, 8VC—as well as a handful of others who are working at companies like Rippling, which is backed by Founders Fund.

Fortune spoke with 10 current or former Review editors and staffers, including Thiel, and reviewed hundreds of pages of nonprofit filings as well as an extensive network of company websites, LinkedIn pages, and archived newspaper articles to understand how the student newspaper became such a prominent, yet controversial, launchpad into the Silicon Valley tech ecosystem—and to piece together the common thread that bound them together. (Two of the people spoke with Fortune on condition of anonymity, and one asked to remain confidential in order to discuss some of the newspaper’s controversial articles.)

“Now that I look back at it—it’s been a big part of what I did,” said Jackson, the Review editor and early PayPal employee who would go on to set up a conservative and Christian market-focused publishing company with Review cofounder Norman Book and author a book about PayPal. Jackson says he has recruited Review alumni, pitched them for investments, and brought them on as advisors and directors at tech startups he has founded over the years.

Former Review staffers say that the journal attracted a group of contrarian, free-thinking college kids some have described as outcasts who, despite being predominantly conservative or libertarian, disagreed on politics and internally debated the premise of stories published in the newspaper over the years. Decades of pages of the Review point to another shared characteristic: a belief that their worldview and the Western value system were under assault both on their university campus and across the nation. As a result, those students would repeatedly come out swinging at their ideological opponents, starting in the pages of the Review—and, in some cases, throughout their subsequent careers.

The early days of the Stanford Review

The Stanford Review was one of a series of conservative campus newspapers that popped up across the U.S. in the ’80s. The first of its kind, the Dartmouth Review, ended up fostering conservative commentators, writers, and television personalities like Gregory Fossedal, Laura Ingraham, Dinesh D’Souza, and Joseph Rago. It’s not so surprising that, on a campus ingrained in Silicon Valley tech, the Stanford Review has cultivated so many tech investors and engineers.

At the time the Review came into the picture, Thiel was a philosophy undergraduate at Stanford. And the university was undergoing an ideological transformation. There was the now-infamous march with presidential candidate the Rev. Jesse Jackson at which students chanted: “Hey hey, ho ho, Western culture’s got to go.” One year later, Stanford would replace its Western Civilization course with Culture, Ideas & Values, aimed at incorporating more works written by women and people of color as well as non-European historical studies. (Thiel and David Sacks, an early PayPal executive and a founder of Craft Ventures, would later cite a series of Review articles and anecdotes in the book they wrote on the topic: The Diversity Myth.)

Much of what has been published by the Review over the years revolved around campus news or foreign politics (with little on business or technology): stories on the connection between the George W. Bush administration and Stanford’s Hoover Institution; the controversy surrounding a campus-wide boycott on grapes; or why Condoleezza Rice should have been considered for the role of university president.

But a key part of the Stanford Review’s initial mission was to be combative with the majority on Stanford’s largely liberal-leaning campus by presenting alternative views—and to spark “much-needed debate,” according to the first editor’s note in 1987. The methods students used to deliver those alternative views varied from thoughtful analysis and reporting to provocative—or outright offensive—opinion pieces. Max Chafkin, who authored a biography of Thiel, wrote about a “long day at the end of 2019” spent in the Stanford archives, reading through issues of the Review. “To flip through the pages…is to be continually flabbergasted that the authors managed to amass so much power in the decades that followed without suffering any apparent blowback,” he wrote in his book, The Contrarian.

A 2004 story ran with the headline “Homosexuals Will Weaken Marriage.” A brazen column written by Sacks on “glory holes” in 1993 ended up featured in the New York Times. Infamous in Review history is a string of excerpts of articles written by Ryan Bounds, including one in which he likened multiculturalism efforts to a Nazi book burning, that surfaced shortly after he was nominated by President Trump for a seat on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. The White House ended up withdrawing his nomination amid the backlash.

Some writers have apologized in the following decades. Sacks said at the time of the New York Times story that he was “embarrassed by some of the things I wrote in college over 20 years ago, and I am sorry I wrote them,” and that he was “horrified” by his old views on homosexuality. Bounds said he should have been more respectful and had used “overheated rhetoric.” (Sacks and Bounds didn’t return requests for comment for this article.)

Thiel told Fortune he believes in “maximalist free speech—especially of the sort that has a political valence,” defending Bounds’ articles as “well within the zone of reasonable discourse.” And he came to the defense of the Review publishing some of its more controversial pieces, even “if there were specific stories I would not personally have written.”

Speaking more broadly, Thiel says that the Review became “markedly less controversial” in 2002, around the same time that articles began to be published on the internet; he says that the internet has made it harder for undergraduates to explore ideas or say controversial things that they might end up changing their mind about.

“A lot of articles in the 1990s—what you have to contextualize is these were pieces [written] in a context where they thought it would be read for one week in a college setting—not where it would be on the imperishable internet for decades to come,” Thiel says.

Other editors who spoke with Fortune chalked up some of the more contrarian pieces to argumentative 20-year-olds who wanted to stir the pot. “If it doesn’t make waves, if people aren’t talking about it, it’s irrelevant,” says one editor, who would only speak on the topic anonymously. “That has to be understood.”

Anyone who dares to read back through the Review’s archived pieces on homosexuality would be hard-pressed to miss the irony between the lines, as Thiel—and several other former editors or writers—are now openly gay. One former editor laughed when he brought it up: “I’m gay—as are about one-third of the former Review editors, it turns out,” said Jeff Giesea, who helped Thiel set up his hedge fund in the late ’90s, then later founded B2B media company FierceMarkets.

To PayPal and beyond

In 2007 Fortune immortalized the descriptor “PayPal Mafia” in a story detailing how so many tech luminaries like Thiel, Elon Musk, and Reid Hoffman got their start at the payments company. But many of the company’s earliest employees likely wouldn’t have arrived at PayPal in the first place without the Review. Martin was one of them—as were Jackson, Rabois, Sacks, Aman Verjee, Nathan Linn, and Bob McGrew.

Thiel hired a number of Review staffers between 1999 and 2000 when he was starting the company that became PayPal, he says, noting that he wanted to work with people he considered friends and that he bonded with on some level—particularly during the ups and downs of the period now known as the “dotcom bubble.”

“There certainly wasn’t a sense that [working for Thiel] was an open invitation to anyone,” says Henry Towsner, who was editor of the Review in 2002. “There wasn’t anything formalized—or even necessarily overtly intentional” about the connections, Martin says. “It just kind of happened.”

Though not for everyone. As several former editors acknowledged, while there have been many female writers and editors for the Review since its first few years in circulation, not many of them ended up in Thiel’s tech orbit—Tayler Lonsdale and Assemble cofounder Lisa Wallace, both Review editors who went on to work at Palantir, being two of the few exceptions. The Review alumni network is predominantly male, though that has, slowly, started to change over the years, with more recent Review alumnae including Antigone Xenopoulos, who interned at Palantir, or Anna Mitchell, who was an associate at 8VC and is now a recruiter at Founders Fund portfolio company Rippling.

For those who did end up in the tech orbit, Thiel companies were sometimes just a launchpad. Sacks went on to run the multibillion-dollar venture capital firm Craft Ventures, which has backed Airbnb, Lyft, Palantir, and SpaceX. Verjee, who is still chairman of the Review’s affiliated nonprofit organization and mentors students, went on to become COO of early-stage VC and accelerator 500 Startups (he later set up a VC secondary fund). Bob McGrew is vice president of research at Microsoft-backed artificial intelligence juggernaut OpenAI. Giesea founded FierceMarkets, a B2B media business focused on health care. Premal Shah cofounded the microloan startup Kiva, and Jackson cofounded a crypto ownership registry called TransitNet. Lonsdale, who now runs 8VC, has cofounded companies like Addepar and OpenGov.

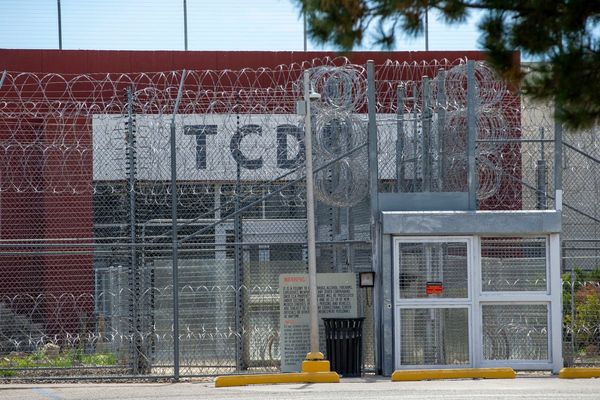

Some of the companies or organizations Review alumni have launched or ended up working for are controversial in some way. Palantir has been contentious owing to its ties to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (a former staff writer said the controversy around Palantir made it all the more alluring to Review writers). Lonsdale is planning to set up a new university in Austin that is teaching what it calls “forbidden courses.” Rippling, a Founders Fund–backed company that has attracted Review alums, is run by Parker Conrad, a founder who had resigned from human resources company Zenefits over an insurance scandal and ultimately had to settle with the SEC. (David Sacks succeeded Conrad as temporary CEO of Zenefits. At the time of the settlement, Conrad said he was pleased to have reached an agreement with the SEC and was “incredibly proud” of what he had built at Zenefits.)

One former writer notes there is a through line that clearly connects the Review bunch: A “disdain for liberal orthodoxy and identity politics—things like political correctness,” this staff writer says, adding, “They sort of see it as emblematic of a society governed by convention and not free thinkers.”

But most of the former editors who spoke with Fortune emphasized that the Review network is intellectually diverse and object to the notion that it is monolithic. As a handful of editors pointed out, some Review alumni vehemently disagree on which political candidates they support, fiscal policy, or whether they think the U.S. should support the war in Ukraine.

“There is more political diversity among Review alums than people might expect. I think we’re seeing that play out right now,” says former editor Giesea.

Jocelyn Mangan, founder of Him for Her, a social impact organization that specializes in boosting diversity on corporate and startup boards, argues that cognitive diversity can really only come from a network that spans race, gender, geography, age, educational background, and socioeconomic experiences—diversity most major Silicon Valley networks and early-stage companies and boards lack. Networks like those from the Review, where people go on to work with and for one another, can be insular and may not be privy to the voices or perspectives that are missing, according to Mangan. “I really think it comes down to human nature network behavior—of picking who everyone thinks is the safe answer, which is who I know,” Mangan says. “That ultimately is the riskiest answer, because it may mean that you don’t see around that corner.”

The lasting impact of the Review

In the end, Thiel says, the Stanford Review has not been very effective in changing Stanford’s campus, one he describes as too conformist, with little room for heterodox thought. But he contends the Review was “very formative” in making people more independent in their thinking—something, he notes, in some context, would help people succeed in Silicon Valley—if not change it.

To his credit, it’s Thiel’s bold swings on some rather unusual ideas that have made him a billionaire—his belief that payments would go digital, that Bitcoin would become valuable, or his $500,000 check to a Harvard sophomore building something called “Thefacebook.” (Thiel is also well known for predicting the 2008 housing market crash, though his strategy for monetizing it was not a success.)

As Jackson puts it, of working at PayPal: “There was never a litmus test, and they weren’t political ones per se—it wasn’t Republican versus Democrat,” he notes. Instead, it was the thinking around letting the market work itself out, or how technology could end up functioning in people’s lives: "That was the kind of stuff that we were all thinking and believing, and it definitely has the lineage that you can tie back to the Stanford Review," Jackson says.

Though even as Review alums have amassed fortunes, built huge companies, and formed powerful networks, some quandaries that stumped the young editors back in college seem to still linger today. As Thiel wrote in April 1989 in his parting editor’s note: “I’ve learned a great deal as editor, but I still don’t know how one convinces people to listen.”