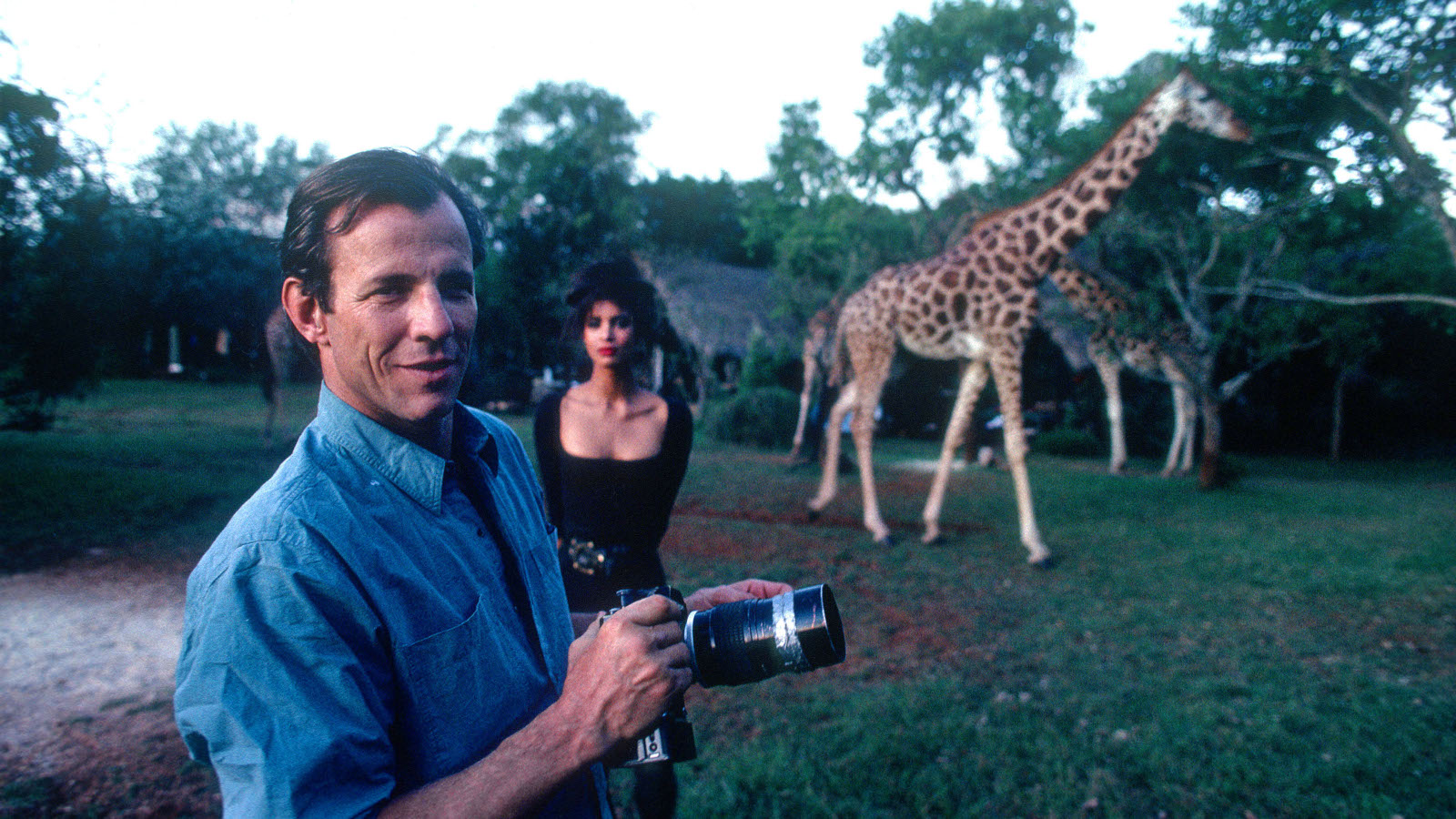

Like most people, I first came to know the legend of Peter Beard, through the image he projected in his photographs from remotest Kenya – scribbling in his journal while hip deep in a Nile crocodile, say – a safari-jacketed image like something out of silent pictures. ‘Half Tarzan, half Byron’, as the editor of Interview magazine, Bob Colacello, once described him.

In the early 1960s, when he was in his mid-twenties, Beard released his totemic book The End of the Game, a meditation on the natural world, on colonialist East Africa, and on his own self-mythology somewhere therein. And this myth, and this image of a sort of post-colonial adventurer with movie-star looks, society girlfriends, and rock star buddies, made Beard a central character on the moodboards of brands and magazines from then on, made him a de facto pioneer of the kind of world- and brand-building that defines our visual and commercial age.

A card-carrying member of the jet set, who had his 40th birthday party at Studio 54, Beard was, also, a diarist both loved and loathed by Warhol, and a collage artist about whom Francis Bacon wrote a fan letter to the Getty museum. To some, though, Beard the person was little more than a bore, a cocaine Cassandra, incessantly ranting about the ruin of the planet through our plunder and consumption of resources. He was also very definitely a narcissist, bigoted, violent, and worse. For all the valorisation, Beard was a deeply flawed and controversial figure, perhaps a near perfect expression of the American id, embodying the myriad awful mess of contradictions of 20th century man.

Writing the life of Peter Beard: from Kenya to Tanzania, Cassis to Venice, and beyond

Soon after Beard mysteriously disappeared from his Montauk home in April 2020, in the earliest, delirious days of the pandemic, I was invited to write his biography and leapt at the chance. Not least because Beard, as a person, artist, and self-made myth, sat on so many of the cultural laylines I have been fascinated with my entire writing life. From entitlement and privilege (descended as he was from two American fortunes, tobacco and the Great Northern Railroad), to the projection of an identity, performative masculinity, colonialist iconography, Beard seemed like a great aperture through which to write about … everything.

I had known Beard a bit for the last six or so years of his life, and would ultimately talk to dozens of his friends, lovers, collaborators, and debtors, but while we were all still very deep in lockdown in New York, I was deep in theory, trying to unpack the very potent image Beard had created. One of Beard’s best-known works, of a nude Maureen Gallagher feeding a giraffe at midnight on his Hog Ranch property outside Nairobi, for example, is titled Beyond Gauguin, and I found this too to be revelatory, reading as I did in Beard’s pictures and collages made in East Africa a kind of Orientalist gaze.

I have always found there to be, creeping around the edges of Beard’s pictures, a bit of a fetish for exoticism – a tokenism, surely, and a kind of fantastical othering of Kenya, creating a magical kingdom of Maasai and lions that might scan in a pavilion at [Walt Disney World’s] Epcot Center: a land of great big beasts, broad horizons, and Stone Age tribesmen just barely if at all raising a fig leaf to cover themselves. And, as I did several times in writing the book, while writing about Beard’s particular expression of these tides, I made a note to myself that, at some point down the line, I would follow these elsewhere: going to French Polynesia, for example, to consider the ways in which Gauguin and his own myth-making helped to shape our ideas and images of paradise.

When travel restrictions began to loosen somewhat, in the beginning of 2021, I followed Beard’s footsteps to Kenya – quite literally, walking the field in the Masai Mara where in 1996 he was trampled and gored by an elephant, with the guys who had been with him at the time. Later, I went to the Serengeti, just across the border in Tanzania, to try to see the way Beard had when he was making his earliest wildlife photos, and tried to write my way to an understanding both of the man and of the cultural and artistic elements at play.

From East Africa, I went to the Dirty Rotten Scoundrels’ south of France, to Cassis, where Beard’s cousin Jerome Hill had lived and built a community of contemporaries, from Picasso to Lucien Clergue to Bardot, and where Beard had spent a lot of his time, both as a young man and then in the early 2000s. I finished the book in Hill’s former home there, which is now an artist retreat, and, rather than go home and spin out on LinkedIn or whatever, went to visit friends in Venice, which was just then reopening.

In Venice, I thought I might try to take my own amateur travel photos a little more professionally, and might continue to chase the threads of thought I’d found so exciting in writing about Beard’s art and image. I did, for example, go to French Polynesia, and tried to unpack our ideas of paradise as a prelapsarian beach in the global south, tried to consider what we have inherited from Gauguin’s hysterical projection, and how that informs the way we think of ourselves and the places we visit when we travel.

In the two years or so since I finished the book, I have travelled to Hawaii and to the Galapagos, to Southeast Asia, Central Europe, Morocco, Lebanon, Iraq, and elsewhere, trying to write about the stories we tell ourselves about who we are on our travels, what cultural narratives we fit ourselves into, and where those come from.

There is so much richness and human oddity in the ways we project our own cultural and historical frameworks onto the people and places we encounter on the road, so many points of entry to understanding what makes us us, about what we hold dear and what is possible out there on the road. Two-plus years’ reporting and writing and thinking and photographing and what began as a sort of postscript to the book seems to have become a whole new project of its own – something else I have to thank the journey of trying to understand this controversial enigma of a man for.

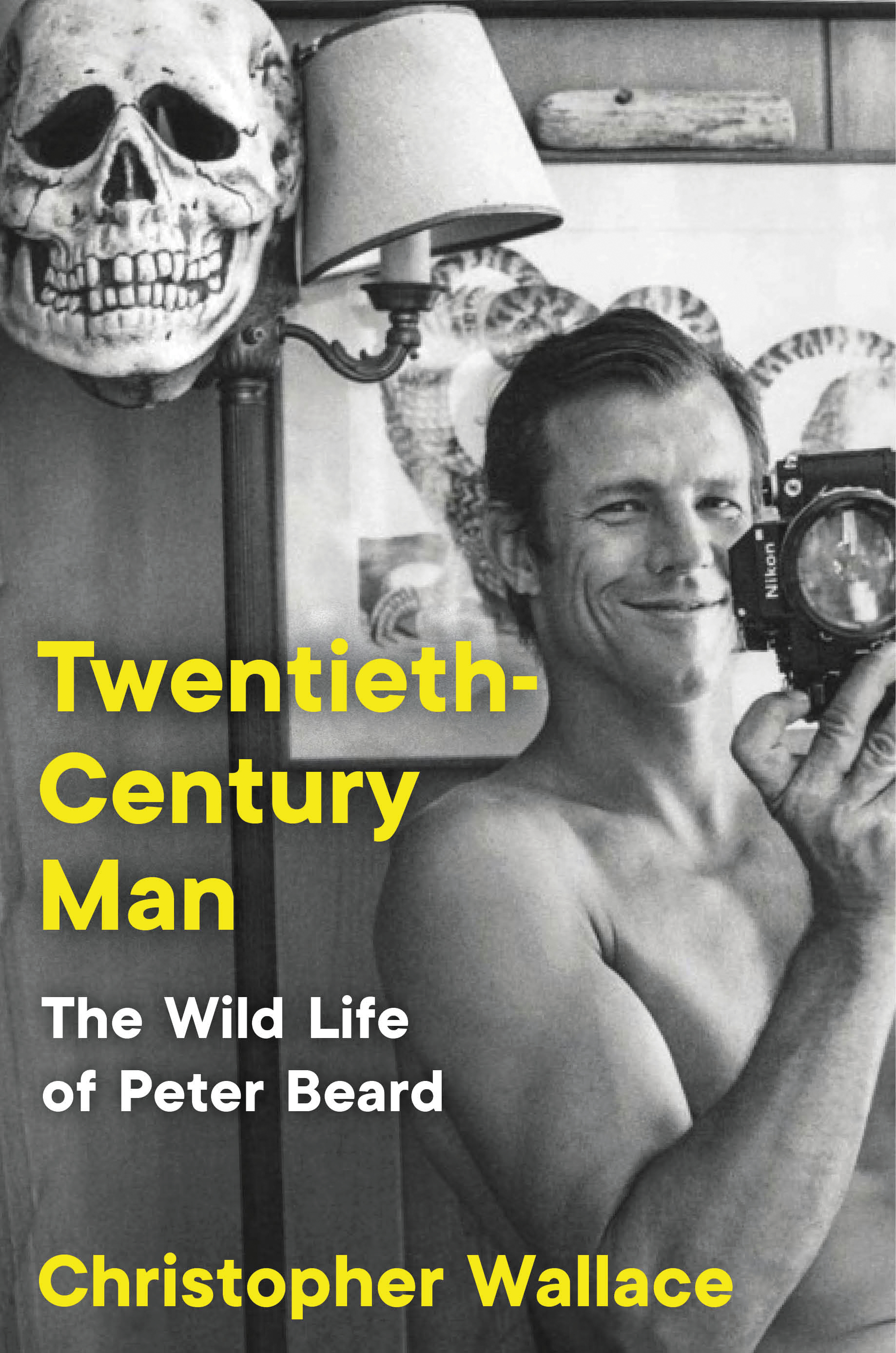

Twentieth-Century Man: The Wild Life of Peter Beard by Christopher Wallace is out now.

Also available from amazon.co.uk