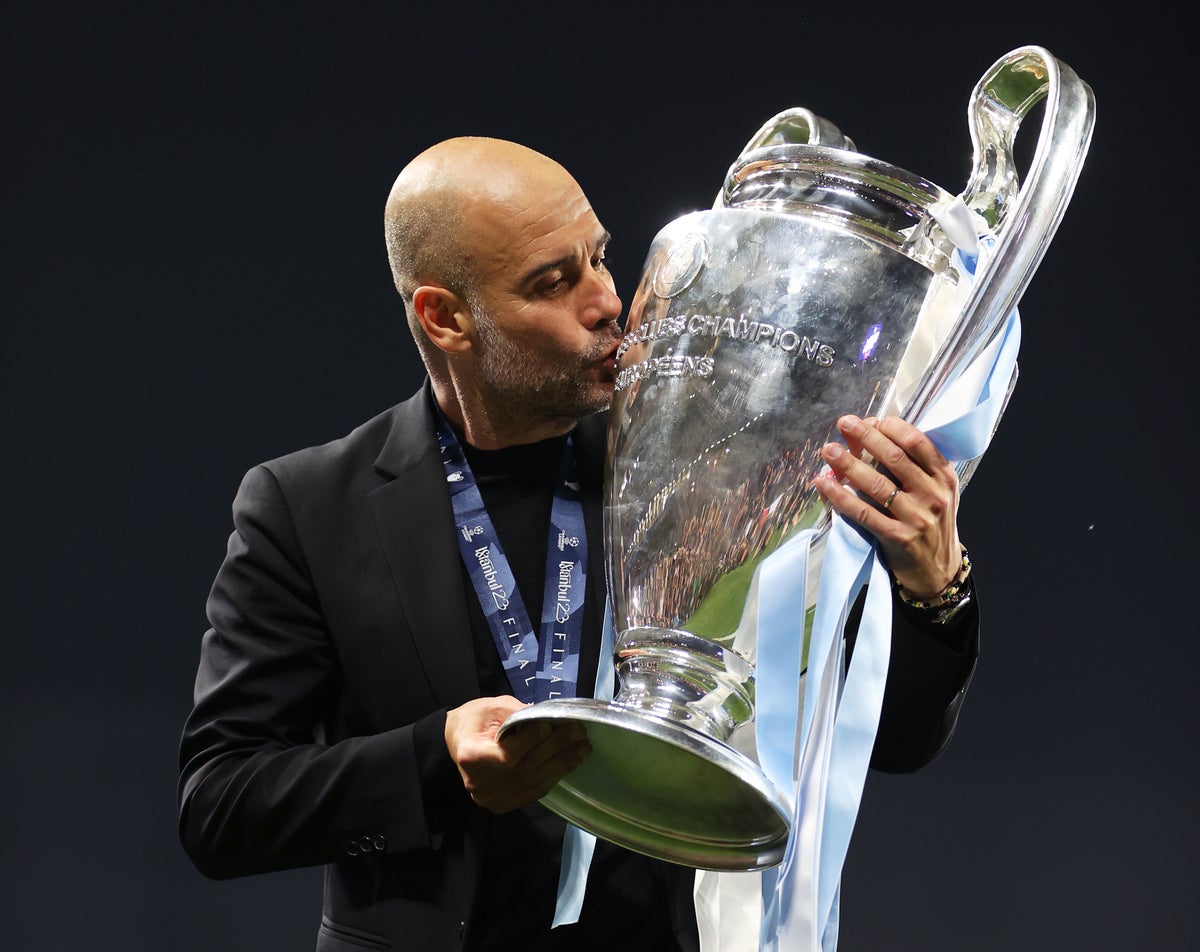

As Pep Guardiola sat with his fourth Champions League medal around his neck, his mind went back to his very first, as a player with Barcelona in 1992.

“It was only the day after that I realised what I had done,” the Catalan said. In the most immediate terms, Guardiola has at last won the grand trophy that both he and Manchester City so desired, delivering the European Cup to Abu Dhabi. Guardiola himself has been an influential ambassador in this regard.

The club hierarchy of course went to him as he is the best manager in the world, maybe of all time, with this second treble and third Champions League offering persuasive arguments. If Guardiola hadn’t yet realised what he’d done, though, he obviously knew all of this had done something to the entire discussion around his role.

“It’s a big relief for the club… for the institution,” he said. “Now, nobody asks me if we will win the Champions League.”

They will ask how and why, though. That is the discussion that comes up after any great feat, as everyone seeks to take example from how such excellence was achieved. It does take on another dimension with City given the uncertainty that continues from the Premier League’s charges, although the club insists upon its innocence.

While Sir Alex Ferguson did message Guardiola due to their personal relationship, it was conspicuous that no other Premier League club offered official congratulation to City through their social media channels. A “fury” persists within the competition.

Guardiola persists at City, though, despite a previous feeling he would leave once the Champions League was secured. Those who know him now believe he doesn’t just want to retain the trophy, but win his fourth and fifth, as a manager, to truly secure his legacy as the greatest ever. Guardiola of course has an ego too, even if it is more internalised than, say, Jose Mourinho’s. It’s really a prerequisite at this sort of level.

He is now seeking to go a level beyond. Guardiola wants to do what he could and should have done as manager of Barcelona, when that great side came so close to winning four Champions Leagues rather than just two.

The Camp Nou, and La Masia, is what so much of this story goes back to. One of many echoes around the game right now, though, is many pointing out that 2008-12 period of success is covered by charges against Barcelona for payments made to Jose Maria Enriquez Negreira, the vice-president of Spanish football’s refereeing committee. The sport has an increasing legitimacy crisis, as interests like autocratic states and private equity approach it from all angles.

Those close to Guardiola insist he did not know anything about this.

He does know football to a more profound degree than almost anyone in the history of the game, which is why these wealthy clubs keep looking to him. The argument that he should try and do it at a lower level is a little misplaced, since he keeps doing it at the elite level.

It is why the story of the first state club winning the European Cup must start at the end, and the manager who brought it all to a peak. The sense of completion for a political project is also complemented by the satisfying sense of symmetry for Guardiola, as he brought his career full circle.

The root of the sensational run that brought City the treble was Guardiola going back to his own football roots by implementing the “Johan Cruyff box” that Barcelona used in 1992. It didn’t just solve the “problem” of fitting a minimalist goalscorer like Erling Haaland into such a collective, but maximised everything.

This divine connection in a football sense does reflect a slight disconnect in the wider football culture of the club. While City are one of the English game's great institutions, with their own rich history that the new hierarchy have sought to celebrate, the post-2008 executive still effectively treated the club as a blank slate. They looked around the game for the equivalent of “the Apple of football”.

That, through 2008 to 2012, was clearly Guardiola’s Barcelona. City knew they could not just entice the Catalan over, however, no matter how much money they offered. It was also their grand plan to go much further than just hiring the manager. This had been Roman Abramovich’s great failing in trying to entice Guardiola to Chelsea for so long. The coach had concerns about the structure of the club.

So, in one of the most audacious plans ever seen in football, the Abu Dhabi hierarchy sought to wholesale incorporate the Barcelona brains trust. Chief executive Ferran Soriano and director of football Txiki Begiristain soon arrived, with many other staff members following.

This was just as crucial to the success as building an entire club structure up to Guardiola’s ideology, since the coach felt a debt towards Begiristain for first trusting him as a novice at Camp Nou in 2008.

It is why Guardiola is at the club. After the game, the Catalan made a point of thanking Soriano, Begiristain and chairman Khaldoon al Mubarak.

“The second thing is for my sporting director and CEO and chairman,” Guardiola said, after initially praising Internazionale for the way they made City fight. “Normally, when you don’t win the Champions League after so many years you are sacked. How many clubs destroy the project? It looks like this competition this year was in the stars.”

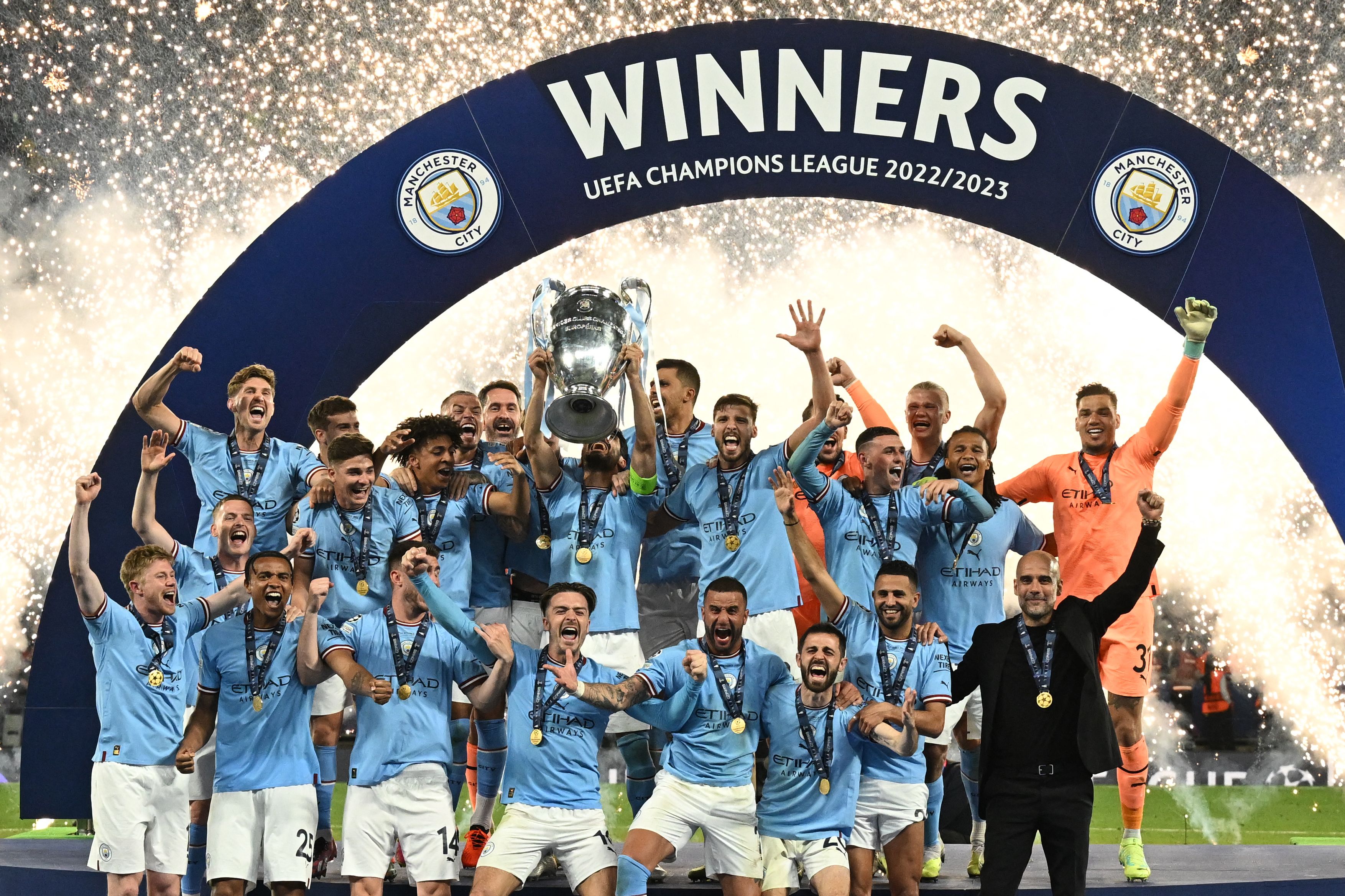

You could certainly say it was an inevitability, but that wasn’t down to anything metaphysical. It was down to sheer force of numbers, especially in investment. Because, around the same time Guardiola was thanking his superiors on Sunday morning in Istanbul, the United Arab Emirates’ Minister of Interior and Deputy Prime Minister Saif bin Zayed Al Nahyan went even further. He put up a social media post that lauded “His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed” for how this achievement was secured “under your patronage and in your presence”. He then congratulated Mansour before saying “congratulations to all Emiratis and all football fans”.

It overtly articulated how politicised this entire event was, even as so many people just pointed to Mansour for attending his second game. Of even greater relevance was that “presence” of his older brother, Mohammed bin Zayed.

This is where all of the discussion around City and their brilliance must necessarily go way beyond football.

It is after all why the Barcelona hierarchy are at the club. Abu Dhabi could afford it.

They have also completely upended the structure of the sport

The club has huge value to the emirate as a political project. The most common term for this is the now simplistic “sportswashing” but it is really something much more complicated.

Abu Dhabi is seeking to preserve its state structure in the long term, through the normalisation of the state as it undergoes a wider process of economic diversification away from oil. It should be added that state structure has brought huge criticism from human rights groups, for issues including suppression of dissent to the labour system that was such a problem for Qatar before the World Cup.

That alone should provoke the most profound discussion about where the game is going, and how it is used, especially as so many private equity groups circle what is left behind. What is this all for?

Many long-time City fans touchingly cried tears of joy as the team lifted the trophy on early Sunday morning, and that is impossible to begrudge. It’s also impossible to detach that from the wider issue. Even fans with the most conflicted feelings on all this will feel some gratitude for the glory in this moment.

This is partly what these autocratic states are playing on.

They have also completely upended the structure of the sport, while seeking to preserve the structure of their states.

The very fabric of football has changed. Some of that was symbolised in City’s surge to the treble.

As well as so comfortably finishing ahead of England’s biggest clubs in the Premier League, Guardiola's team brutalised the Champions League’s most historically successful clubs in Bayern Munich and Real Madrid. It says enough in itself that European royalty like Inter could take pride in just giving City a proper game.

That’s how much the sport has shifted.

It should always be stressed at this point that football had a growing problem with financial disparity from the beginning of this millennium, and that establishment clubs being challenged would usually be a good thing.

It’s just that state ownership isn’t the way to do that. Before you even get to the more serious moral discussions, it actually worsens a growing problem, narrowing the field of potential winners by raising the threshold required to compete. That could be seen in a fairly drab Champions League this season. Its elite end felt so small. Such factors are why comparisons with Manchester United's 1999 team are pointless. It was a completely different football world, one where the Premier League was ranked the sixth in Europe by Uefa and the match-winning goalscorer was signed for £1.5m from the Norwegian Tippeligaen.

This is now a world where a series of escalating economic issues forced the introduction of Financial Fair Play rule, that greatly constrain potential expenditure. The big question is what the football world would look like without such regulations?

Even with them, the game has a lot to face up to. City’s treble is a monument to that, and a huge challenge for everyone else to scale.

It feels like a wall has been broken by the club at least in lifting the Champions League, and the feeling now is that Guardiola will go on to win it again and again, just as his team has done with the Premier League.

The Catalan and his Camp Nou principles have elevated all of this, but a considerable platform was constructed in Abu Dhabi.

It now hosts all three major trophies, and a huge discussion for the game, especially amid the context of LIV Golf.

The wider sport is only belatedly realising what is happening.