Whoever came up with the time-old adage “pain makes you stronger” never considered this: For people suffering from endometriosis, pain might just put them at risk for a stroke.

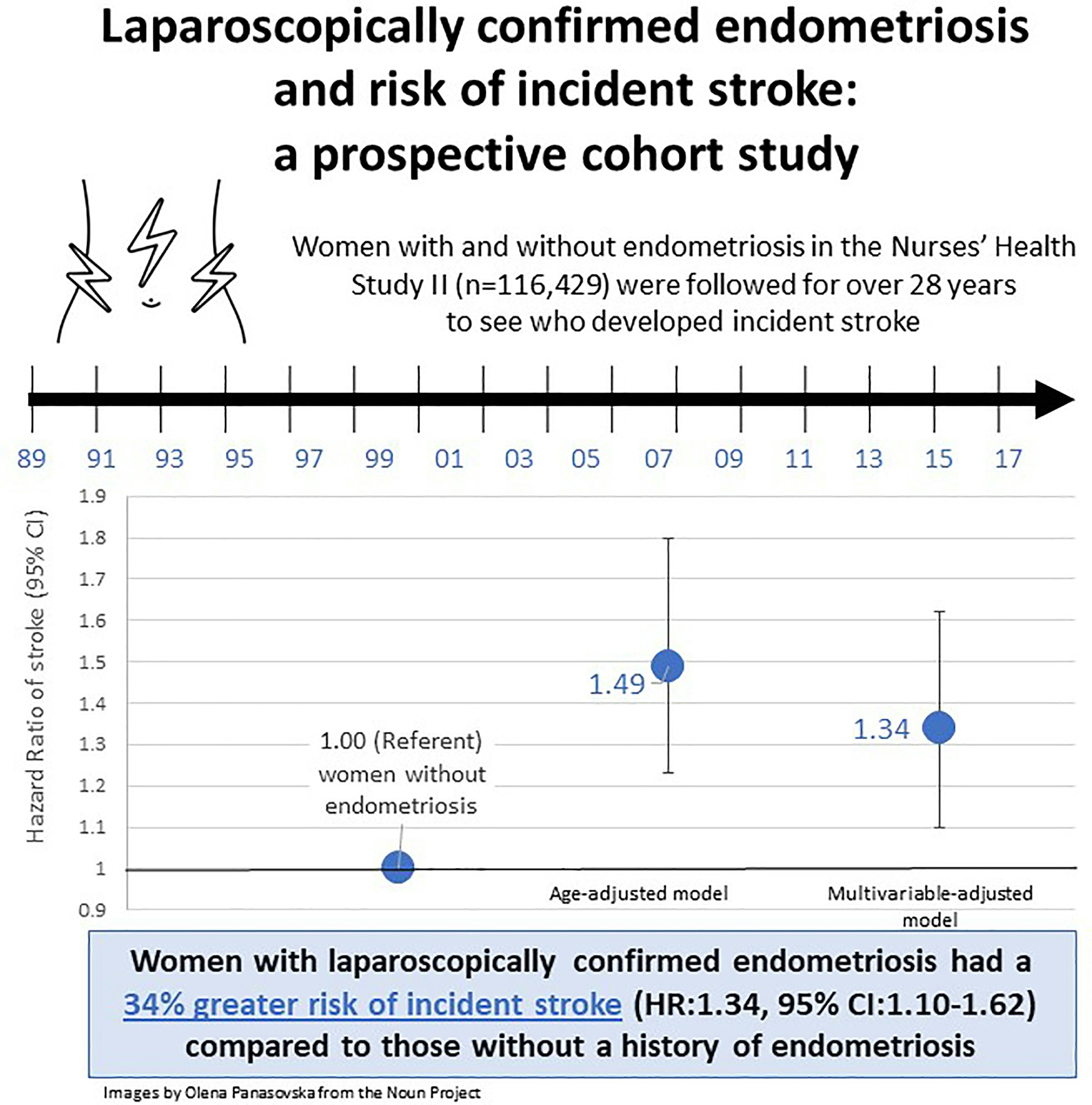

According to a study published Thursday in Stroke, a journal of the American Stroke Association (part of the American Heart Association), people with endometriosis — a common gynecological condition marked by pain in the pelvis and back, painful and heavy periods, and infertility — were at a 34 percent greater risk of developing a stroke compared to their non-endometriosis peers.

The researchers found part of what may play into this increased risk calculus are surgical procedures used to treat endometriosis like hysterectomy (removing the uterus) and oophorectomy (removing the ovaries), as well as hormone replacement therapy used to treat menopause.

Here’s the background – Over the years, there’s been mounting evidence pairing endometriosis with poor cardiovascular health. Prior studies have found endometriosis, which affects five to 10 percent of reproductive-aged women globally, appears to spike a women’s risk for coronary heart disease, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol.

A reason why may be inflammation, and lots of it. Endometriosis arises when endometrial tissue — the stuff lining the inside of the uterus — grows where it’s not supposed to be such as outside the uterus, on the ovaries, or inside or outside the intestines, Dr. Sanjay Agarwal, director of Fertility Services in the Department of Reproductive Medicine at UC San Diego Health System, tells Inverse.

During the menstrual cycle, says Agarwal, these misplaced pockets of endometrium respond to hormonal signals, like estrogen, much like they would if actually in the uterus. But the cyclical thickening, breaking down, and bleeding leads to a maelstrom of far-reaching, systemic inflammation that continues throughout a women’s reproductive years until she hits menopause when estrogen levels naturally tank.

What’s new – Researchers from various academic institutions across the U.S. analyzed medical data of over 110,000 female nurses, aged 25 to 42, who were enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study II, a group first established by the National Institutes of Health to examine how lifestyle habits or other factors impacted a woman’s chance of developing chronic diseases over time.

Looking at questionnaire data collected from 1989 to 2017, the researchers identified 893 cases of stroke (people who had a history of stroke, heart attack, cancer, or coronary artery bypass surgery prior to 1989 were not included). Those who were clinically confirmed to have endometriosis (through a surgery called laparoscopy) had a 34 percent greater risk of stroke compared to women without endometriosis regardless of their age, past medical history, body mass index (some studies suggest a higher BMI correlates with a greater chance of stroke), infertility history, or menopausal status.

The relative risk appeared to hike to 39 percent if a woman with endometriosis had a hysterectomy, oophorectomy, or both. It’s hard to make out the significance or takeaway of this risk. Some research has found that even without endometriosis, gynecological surgeries like hysterectomy carry a high chance of stroke, Stacy Missmer, the paper’s senior author and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, said in a press release.

According to Agarwal, this hike could simply be the added risk of surgery over the underlying risk since going under the knife was the norm in treating endometriosis 20 to 30 years ago.

“Today, we’re finding better, conservative management for women with endometriosis so hysterectomy and oophorectomy are probably being performed less commonly,” says Agarwal.

Why it matters – “[These findings] bring to light the necessity to consider gynecological history when assessing cardiovascular and stroke risk for women,” Lacy Alexander, an endometriosis researcher, and professor of kinesiology at Pennsylvania State University, writes to Inverse.

Having that conversation is especially crucial as endometriosis isn’t always detected or managed early enough.

“Women suffer, on average, between six and 12 years before someone suggests a diagnosis,” says Agarwal. “The delay in diagnosis is in part because patients don’t say ‘Hey, doc, I’ve got pain’ and healthcare providers don’t ask. There’s broken dialogue.”

The study’s findings may help women overall make better, well-informed health care decisions regardless if they have endometriosis, says Christine Metz, an endometriosis researcher at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York.

“Hysterectomies are the second most common surgery performed on women of reproductive age (number one is a c-section) and it is reported that many of these are elective (i.e. not needed when other options are available),” Metz writes to Inverse. “Having this information may help patients decide whether or not they should have a hysterectomy when other choices are available.”

“[These findings] bring to light the necessity to consider gynecological history when assessing cardiovascular and stroke risk for women”

Digging into the details – While Agarwal, Alexander, and Metz all agree these findings give shape to the black box that is endometriosis and heart health, there is the issue of generalizability. The Nurses’ Health Study II was predominantly made up of white women — 94 percent, to be exact — of similar socioeconomic status. While stroke is the leading cause of death for all women in the U.S., studies show Black women have an almost 50 percent higher chance of stroke compared to white women (Hispanic women also have a greater relative risk).

There’s also the question of what kind of strokes – whether ischemic (where blood clots block the flow of oxygen to the brain) or hemorrhagic (bleeding out from a ruptured blood vessel) – are more closely associated with endometriosis. That wasn’t a distinction the researchers were able to suss out with their data but it’s an important one that could inform stroke prevention strategies.

What’s next – Going forward, Leslie Farland, the study’s first author and assistant professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Arizona, wants to see if the findings hold up in a more racially and ethnically diverse population. Most of all, she wants to drive at the why behind endometriosis and stroke.

“We hope to further disentangle the mechanism underlying the association between endometriosis and increased risk of stroke,” Farland writes to Inverse. “Additionally, for women with endometriosis, further research is needed to understand whether there is an opportunity for early intervention to reduce the risk of stroke and cardiovascular disease.”