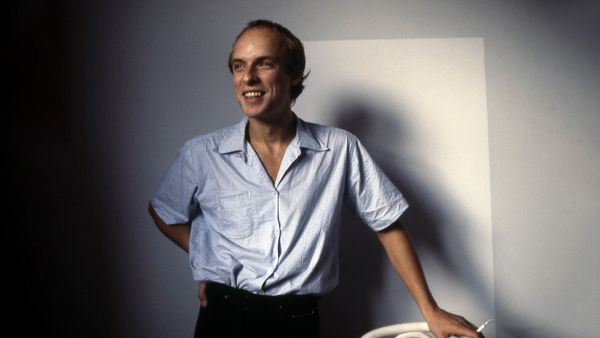

Trevor Horn, the producer who ‘made the '80s’ has broken cover, appearing in a new video for Spitfire Audio, home of his Jupiter sound library.

Seated in his studio alongside Spitfire Audio co-founder Paul Thomson, the pair addressed topics as diverse as the art of sampling, how to get the best from a drum machine and the state of music production today, with some expert advice for up-and-coming music makers seeking their big break.

Naturally, with his own Jupiter library available via Spitfire Audio, the art of sampling was the pair’s first port of call. Horn, of course, was one of the early exponents of the Fairlight sampler that changed music in the '80s.

“The thing about the Fairlight was that it changed the sound of the thing that you recorded,” comments Horn. “It had a certain way of cutting lots of the frequencies off the sound so it was particularly good for basses because it would give you a picture of the bass without all the bottom end in quite a clever way.

“I think that's why it was so exciting back then because it sort of romanticised the sound. Nowadays sampling is incredibly clear, it's perfect and you've got unlimited RAM. Back then, having 8MB of RAM was a big deal, so you'd have to find ways of making things fit.

“The other great thing was that back in 1982 nobody really understood what it did and JJ [Jeczalik, Horn’s Fairlight operator] being a kind of non-musician would constantly sample all kinds of weird things: cash registers, drills out on the road and stuff. So to me that was the sort of a ‘golden era’ back then when you were hearing things that you'd never heard before.

“People were always asking me, trying to find out what I was doing because they didn't understand and I never used to tell them.”

Similarly, Horn was famous for making popular the sound of the drum machine across his countless '80s productions. But which was his favourite, Thomson asks?

“I think the Linn [Drum] 2 for me was the epitome of just about the best drum machine. Although the [Oberheim] DMX was also pretty good. I've still got a DMX. I had my Linn modified so that you could put more top end on the kick drum because that was what we always used to seem to be doing, but to get a drum machine to really work in a track you had to push and pull it a lot in the mix.

“I remember having an argument with an American engineer who was trying to do a remix of Relax for me, the guy that engineered the New York mix. I'd left him with the track, which was where I’d got to after working for a few hours, and when I came back and heard it I said 'You you can't leave it. You can't just leave the faders. You've got to push everything and pull it. Give it dynamics, you know, compress the hell out of it. Do something with it. Mangle it.' You have to be ruthlessly objective, I think.”

And what about the act of creation. Did Horn have any tips up his sleeve for creating similar sonic majesty, Thomson wonders?

“You have to be honest with yourself. You might spend two days doing a new version of your song that you think is great, and then when you listen to it you realize that somehow it's not doing it. But there's maybe two ideas in it that are good so you keep those two ideas and then you try again. And eventually, if you're lucky, the thing will come into some sort of shape.

“Welcome to the Pleasure Dome was really the result of [SARM engineer turned producer] Steve Lipson. I came in the studio one day and we were we were working with two digital multitracks and I remember he said to me 'listen to this', and he'd somehow put the verse and the chorus together by offsetting the two machines so the chorus is playing from that machine and the verse is playing from this machine. It was amazing.

“You couldn't do that with analogue because analogue tape is like elastic. It’s just not accurate, whereas with digital it was perfect. So we could do additive editing, like making video, so Welcome to the Pleasure Dome went from two-and-a-half minutes long to being 15 minutes long. We just kept adding bits. Working digitally we could move anything to anywhere, and that was a new thing.”

And how does Horn feel about modern music making? Can we really claim to be as creative as the pioneers were back then?

“Back in the day, to use a kitchen as an analogy, you made everything from the ground upwards: your sauce, your seasoning, whatever. Now everything's out of a packet. Just add water and you've got it, and so most things are made up of recordings that have already been recorded. You're just rearranging them,” Horn says.

Any tips for working with musicians, asks Thomson?

“The first thing with musicians is you've got to make them feel relaxed. They've got to feel like they can do whatever they want and it'll be OK. If you make them jumpy they'll stop thinking. You don't want musicians to say 'Just tell me what to do and I'll do it.' You want them to be into whatever song you're working on and coming up with ideas. And so I try to leave people alone at the start so that they get to play a little bit and get to feel comfortable.”

And any tips for those looking to produce music and to be as revered as Horn himself?

“My main piece of advice would be to never give up but also be realistic about what you're good at. Loads of the good engineers that I've met are actually musicians who realised that they maybe didn't quite have what it took to be a musician, but they were good at this, they were good at dealing with people. So be realistic about what you're good at and try and get yourself doing that because believe me it'll be hard enough.”

Check out the full interview above. And find out more about Horn’s Jupiter sound library with Spitfire Audio here.