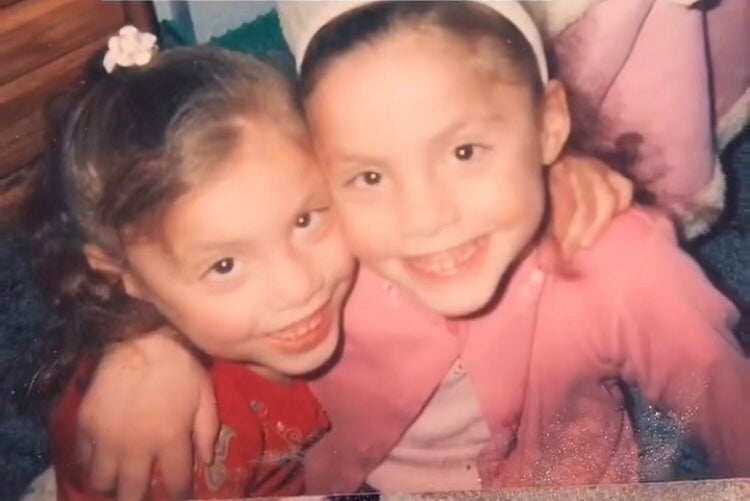

When Gabby Garcia filmed a TikTok video last year, it looked like any other makeup tutorial posted by a 20-something – until she started talking about her twin, Michaela.

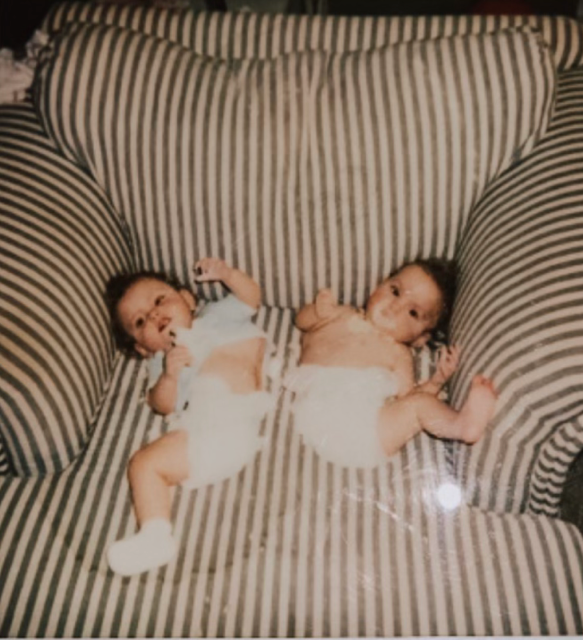

The girls were born conjoined in California and separated at eight months old, split “at the belly button,” Ms Garcia tells The Independent, leaving the twins with one leg each. Their childhood was miraculous and happy until Michaela tragically passed away at 13 after suffering complications from the initial surgery.

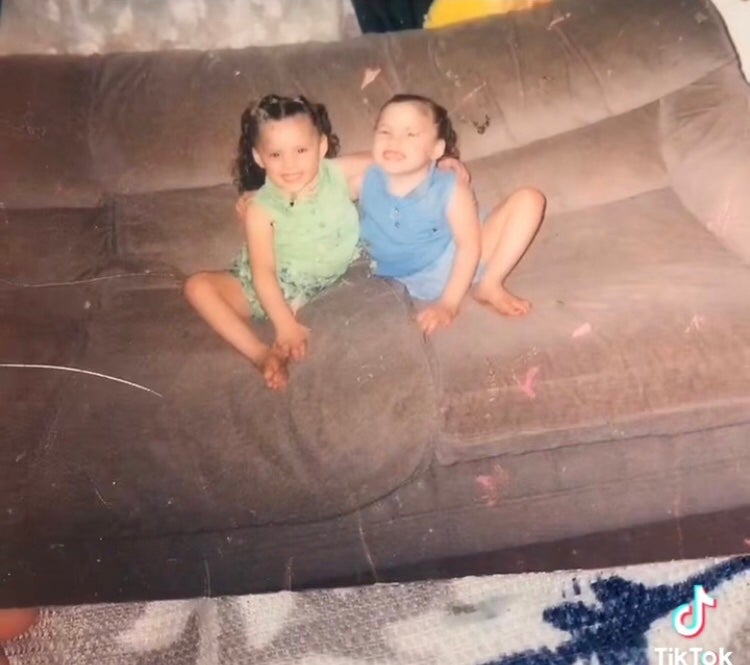

“I was a tomboy, and my twin, she was so girlie and so out there and very, very, very outgoing,” Ms Garcia says. “And she would always tell me, ‘Gabby, please put makeup on with me; let me put makeup on you.’ And I would never budge.

“I was a bookworm, and I was very shy and reserved, compared to her. She was very outspoken and sassy, and I always felt bad, to this day, that I never did” let her apply makeup, Ms Garcia says.

Following Michaela’s death, it took Ms Garcia years to open up about their story – but her twin’s “girlie” passion played a large part in eventually giving her twin the courage to do so.

“One day I kind of picked up makeup and makeup tutorials, and I was looking in the mirror and doing my makeup, and it felt like a very ritualistic experience for me, because we’re identical twins,” Ms Garcia tells The Independent. “And I looked in the mirror, and I could see her looking back at me — and it felt like I was connecting with my sister.

“I kind of fell in love with it, and I always say I hope she’s proud of me; I finally came around to being a girlie girl, and I wish she was here to experience that with me. I feel like I can channel her through me.”

Ms Garcia did begin channeling her sister’s passion and their story onto social media – posting a TikTok late last year that described their rare situation. The former conjoined twin was living with her mother and five siblings in Idaho Falls, where they’d moved from California about a year previously.

The TikTok user had about 80 followers at the time, she tells The Independent. Then she posted the video.

“I didn’t really expect people to take such an interest in it,” she says. “It went completely viral overnight. I ended up getting like 100,000 followers.”

She’s now got about 230,000 — with millions and millions of additional views.

“People were so intrigued,” she says. “So from there I went on and did a couple of storytime videos. I talked about my sister, and people who were very curious about her condition [were] asking the most bizarre questions you can think of about conjoined twins ... I guess the most popular question was, ‘How do you use the restroom?’

“I was like, how do you use the restroom?” Ms Garcia laughs.

“I would try to go on there and kind of answer in a witty way but also educate people, because they’re genuinely curious – and these are like genuine questions. At the end of the day, you don’t see conjoined twins very often, and so I thought it was like the perfect opportunity to use my social media to raise awareness about our condition.

“Also, I wanted everybody to know my sister – and not just my story but her story, because she was not here to tell it. I just wanted to share a piece of her with everybody because she impacts my life every day still, ten years later after she passed away. And so I wanted everybody else to have a piece of her, as well.”

Gabby and Michaela were born to their mother, Karen — who already had a small child — in 1998 after a traumatic pregnancy in which the expectant woman was told by “everyone” to abort the babies, Ms Garcia says.

“The doctor kind of explained it to her in a very crude and very hard way,” the 23-year-old aspiring nurse says. “He printed out pictures of these very deformed fetuses that just looked horrifying, and he flipped these papers over on the table and said, ‘This is what your babies are going to look like.’

“It’s very harsh, but he said, ‘You’re going to need to abort your babies.’ And my mom was just totally taken aback ... this doctor is telling her that we’re going to be monsters and abominations.

“She told me that she walked to the library and she ordered a book about conjoined twins to learn about our condition.”

Her mother was adamant throughout that she would not abort the girls despite pressure from everyone from doctors to strangers to her own family, Ms Garcia says.

“She thought, everybody has a choice in this world, and I’m choosing to keep my babies,” she says. “I think she was like, “No, I’m going to give my babies a chance and I’m going to prove you guys wrong – and we did. And we beat those odds.”

Eventually, Ms Garcia says, a hospital team at Loma Linda reached out to her mother, and that’s where she received care, delivered the girls and saw them separated eight months later.

The girls were literally joined at the hip and shared intestines, a leg and other parts – but each had a kidney, a liver, a heart, lungs and all the major organs in something of a “best-case” scenario for such births. Each was left with one leg while Michaela had a colostomy bag and Ms Garcia a urostomy bag following the surgery.

“The doctors chose to separate us so early because they didn’t want us to be over a year old and go through that traumatic experience of being separated from each other, because it was a very, very intense and risky surgery, and we were so little. They wanted to try and protect us in that way ... to kind of wake up one day and not be connected to that person that you’ve been connected to your whole life.”

Hence Ms Garcia doesn’t remember being physically joined to her twin – though they felt it their whole lives.

“It was beyond the connection of just being your average twin,” she says. “My sister Michaela was somebody that I literally shared flesh with – and so that connection went beyond everything. And we had such an infinite bond that we would sit next to each other, and we would place our scars on our sides next to each other, and we would have them touch, and we would pretend that we were connected still, just to ... feel that connection and that bond.

“We would sit next to each other and kind of wrap our arms around each other and kind of sit in the position we were in when we were conjoined.”

The girls were relatively healthy babies, Ms Garcia says, though Michaela began having serious health problems around the fourth grade, when her bowels collapsed but she pulled through. Things got worse over the next few years, and she was rushed to the hospital in 2011 — only for Ms Garcia to follow soon after with the same issues.

Doctors found that mesh used to create stomach walls for the girls had become highly infected. They were both operated on and kept in the hospital for months but only saw each other once; Ms Garcia was getting better but her twin was not.

“Eventually, the infection from that mesh hit her bloodstream and she became septic, and she got a fungal infection in her body and in her blood,” Ms Garcia says. “In short, I was discharged from the hospital November 4, 2011, and my sister passed away November 5, 2011 – so just within a day of each other, of me going home.

“And I always think that she was waiting for me, that she didn’t want me to be there when she left.”

For years Ms Garcia struggled with grief and survivor’s guilt. But one day last year she woke up and thought, “All this time has passed, and I don’t want all her memory to just die with her,” she says.

“I thought, you are supposed to make her memories alive, and she would do this for you.”

So she opened up about her story and received a reception she never expected. She was also introduced to a new and understanding community of families in similar situations. She’s since met conjoined twins who happen to be nearby in Idaho — and a family in Utah — in addition to connecting with others online.

There are more families out there than people realise, she says, but many don’t feel like drawing attention to themselves.

“Let’s be honest,” she says. “When we were kids ... people called us freak babies. People called us very disgusting things. There was an incident when my mom was at the post office, and somebody ripped the blanket off our car seat and they told my mom that we were freaks and abominations.”

She adds: “It’s crazy to me that people can be so disgusting, because I feel: ‘Don’t’ you think we’re miracles, though? Don’t you think we’re extraordinary? Why is the first reaction to be disgusted by us?’

“That’s another thing, I think, when I went onto social media ... I want conjoined twins to be looked at like we are your average people, and we are just like everybody else.”

Following the viral nature of her initial TikToks, she says, she “took a step back from it and took time for myself ... Talking about our story has been very healing and therapeutic, but it’s brought up a lot of emotions that I guess I’ve been suppressing since I was a teenager – so I took time.”

In recent months, and even this week, she’s been posting again, and Ms Garcia is even considering a podcast and a book.

“I thought, one day we’re going to hit a time where she’s been gone for longer than I had her,” she says. “And I don’t want to regret not talking about her and being open about her.”

When Michaela was alive, she says, “we had these huge dreams. We wanted to grow up and write a book about our life ... She wanted to be famous and do all this cool stuff – and so I felt like I was doing all of this for her. It felt really cool to kind of see a little bit of our dream come true.

“And I felt like there’s a piece of her that I carry with me every day – so I felt like she was there every step of the day during this.”