Elon Musk’s recent takeover of Twitter has thrust Mastodon into the spotlight. Some Twitter users are now trying the alternative network out, while others are struggling to understand what it is and how it works. Mastodon offers a glimpse into democratically run social media — but are we ready to take on that responsibility?

Ironically, much of the talk about Mastodon is happening on Twitter. People are worried about what Musk will (or will not) do with his newly acquired “public square,” including reversing the permanent suspension of Donald Trump from Twitter following the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol.

The response to Musk’s takeover has been a kind of self-imposed deplatforming, with Mastodon seeing a massive surge of interest.

Yet those who have made the switch to Mastodon are now realizing it is not a simple substitute for Twitter. Instead, what we are encountering is a diverse collection of quasi-independent online communities that can be difficult to comprehend.

Some users will no doubt give up and walk away, but what others are realizing is that Mastodon offers a glimpse into a world of independently owned and operated social media that is very different from the corporate platforms we are accustomed to.

Open-source software

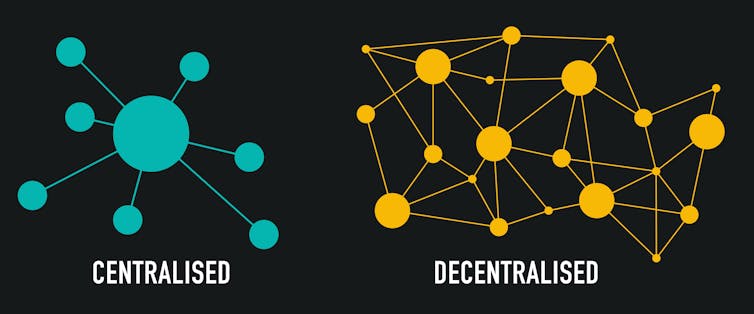

Mastodon is essentially open-source software that can be installed on any computer to host an online community or “instance.” There are a number of good explainers about how Mastodon works, but the key difference is that users come together to create and run their own instances.

These instances can be as large as mastodon.social with 160,000 users or as small as the 15 members on libertarians.social. Separate instances such as these can then be interconnected, much like we can exchange email across separate client devices.

I have been operating a Mastodon instance at the University of Alberta for over a year. My research team conducts experiments and runs workshops on it for students and community groups.

Back to the future

Mastodon belongs to a larger movement called the Fediverse, which scholar Robert Gehl describes as “a network of very small online communities that band together through both technology and shared social values.”

Read more: Citizens' social media, like Mastodon, can provide an antidote to propaganda and disinformation

The groups that choose to join the Fediverse are often seeking a return to a participatory web that some, like tech writer Ben Tarnoff, believe has largely disappeared with the privatization of the Internet.

In fact, this is a movement that resurrects the concept of netizenship, a term that appeared in the mid–1990s but has since largely vanished from popular discourse:

“There are people online who actively contribute towards the development of the Net. These people understand the value of collective work and the communal aspects of public communications. These are the people who discuss and debate topics in a constructive manner … These are the people who as citizens of the Net, I realized were Netizens.”

In fact, Fediverse software is designed to encourage netizenship by fostering small, tight-knit communities in which members are given complete control over the rules, policies, and social norms on their platform. Far from being a utopia, getting along often means hard work and compromise by members of each community.

Trending towards decentralization

Twitter’s creator, Jack Dorsey, has invested in a decentralized social media project called BlueSky which promises to allow users to choose their own platform while still remaining connected to their social networks.

Decentralized social media is the latest Silicon Valley trend, yet the underlying business model of these initiatives remains the same. Personal data is sold to advertisers in a form of surveillance capitalism that compromises our privacy and monetizes our interactions. It is consumption disguised as participation.

By contrast, the Fediverse eschews this practice and enshrines the autonomy and data rights of its users. Critics of the Fediverse seize on this point to argue that these software projects don’t have a sustainable business model, relying on goodwill and donations to pay the bills.

Setting aside the possibilities of a public broadcaster model for social media, this financial reality nonetheless haunts those who may invest time and effort into building online communities in the Fediverse.

Whether the software will continue to be improved and maintained, and how bugs and security concerns will be addressed, remains to be seen. But with a large enough user base to attain significant network effects, it is entirely possible that the Fediverse can become a thriving electronic commons and viable alternative to corporate social media.

A move to the commons

For Mastodon to become a viable alternative, the first step is to create wider public awareness that these noncommercial alternatives exist. Elon Musk is helping to do this, admittedly inadvertently.

The next step is to build the digital skills and resources to use these alternatives. This is where educational institutions and community coalitions can play a role.

At the same time, we need to strengthen the dialogue between the developers of the Fediverse and its users to further improve the usability, reliability and security of the software.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, enough of us must find the individual and collective will to take greater responsibility for the governance of our media system. Perhaps we can start by revisiting the term “netizen,” and make it meaningful again.

Gordon A. Gow receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC)

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.