FEW marks on the landscape say "progress" quite like a rail line.

History is webbed with train tracks, turning frontiers into empires, transporting human ambitions on that long journey from wild dreams to unimagined fortunes.

Indeed, a train track seems to be forged from high-tensile human ambitions. A train track is steely, pushing through all sorts of terrain, taking a sure line from one place to the next.

The joy of a train ride may be in the journey. Kind of like life itself. But the potency of a train track is held in its promise of a destination.

If a train ride is like life, then a train track is like belief or hope.

A train ride lets you feel you're going somewhere. A train track reassures you that you can get somewhere.

Which is why there are few sights more forlorn than a disused rail line. It gets you nowhere. Its very purposelessness is like a fast track to hopelessness.

We human beings need hope. Thankfully, we are adept at finding hope and purpose, sometimes in the remains of what we have discarded. And from pieces of the past, we can create somewhere to set off on a new journey.

We get going once again.

And so it is with the Fernleigh Track.

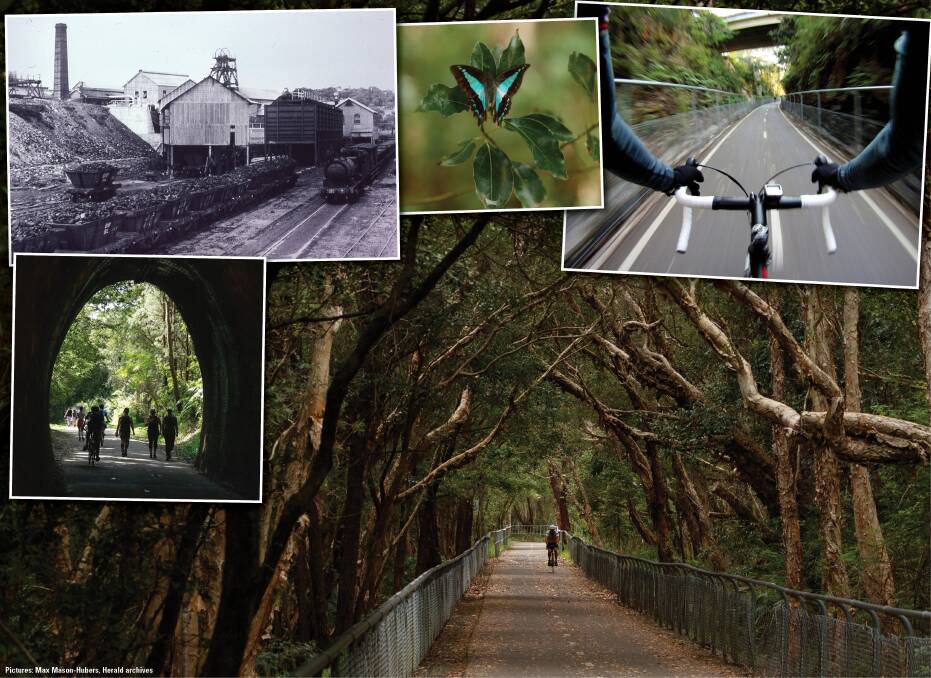

MORE than link Newcastle with Lake Macquarie, the Fernleigh Track joins the past to the present. And it cuts through the very bedrock of this region's existence: coal.

This corridor coursing through communities and bushland for just over 15 kilometres is here because of coal.

It began life as a rail line to transport coal to Newcastle's port from the mines that grew along the coast like heath in the late 19th century.

In 1883, the Redhead Coal Company had received permission to build a private rail line from its proposed colliery by the sea at Redhead through to the main government railway at Adamstown, about 10 kilometres away. Legal wrangles meant construction didn't get underway for six years.

The first load of coal was carried in 1892. However, it came not from the colliery at Redhead but from other operations that had sprouted near the line. In 1895, the New Redhead Estate and Coal Company was formed to take over the assets of the Redhead Coal Company.

Businesses came and went, and collieries along the track had their names changed, but as surely as the rail line pushed ahead, so did the demands of a coal-fired world and a growing industrial city, especially when the BHP steelworks opened in Newcastle in 1915.

The line extended further south to Belmont. The trains began transporting passengers, carrying commuters and visitors to the coast and the lake, along with the expectations of real estate developers keen on opening up land near the rail corridor. So this was a line of the people, as well as of industry.

"It's very significant," says rail historian and author Ed Tonks of the rail line. "It's without peer, because it was the last 19th century railway built in the area to be linked to the last 19th century colliery [Lambton Colliery at Redhead] operating in the area.

"And both those elements were significant in shaping the urban pattern of Newcastle and Lake Macquarie."

Ed Tonks explains those two cornerstones of industrial Newcastle - the rail line and the mines - helped preserve land along the corridor for many years. That land couldn't be developed while the collieries, and the trains, were operating.

From the 19th century and into the 20th, through boom times and bust, trains trundled up and down what came to be known as the Belmont line.

The corridor serviced five major collieries, along with a few smaller operations. Just beyond the corridor, housing gradually replaced the bush, and platforms squatted along the line, cradling waiting passengers.

Yet increasingly, people relied not on trains but cars. Rail was being slowly subsumed by roads.

Regular passenger services to Belmont stopped in 1971, leading to the closure of a string of little stations. And that wasn't the only change. Colliery villages were being transformed into suburbs, as mines shut. The final load of coal to be transported along this line left Lambton Colliery in December 1991.

The Belmont Line fell silent.

Then it fell into ruin. It became an unofficial walking and riding track, an adventure playground for kids, and a dumping ground for everything from rubbish to stolen cars. All the while, Mother Nature worked at reclaiming what was hers, stitching the scar with vines and weeds, and seeding the track with bush.

The old line was disappearing out of sight, because, for many, it was all but out of mind.

After all, it was just another uncomfortable reminder of how the nature of industry was changing, and with it so was Newcastle's rhythm of life. And that rhythm no longer included the reassuring clickety-clack of trains on the Belmont Line.

Yet a few imagined a new life for the corridor. As early as 1987, while trains had been still running along part of the railway, Newcastle Cycleways Movement looked further down the line, to the future. The organisation proposed that once the trains did stop, the track could be converted into a cycleway.

"As soon as the coal line was closed, when it became apparent it was going to close, we began pushing for it," says Sam Reich, President of Newcastle Cycleways Movement.

"It had been an unofficial corridor for a decade, a decade and a half, before the track opened. People were riding mountain bikes over the sleepers."

The idea of creating a path for cyclists and pedestrians seemed to move closer to reality when the Newcastle and Lake Macquarie councils bought the corridor in 1994.

In that year, three authors of a management and action plan for the site came up with a name for the former rail corridor: the Fernleigh Track. That name was touching on the area's coal and rail heritage; "Fernleigh" was what a section of the line and a nearby colliery were called. That name, transplanted from the Old World and redolent of ferns in meadows, was about to be given new meaning - and a new life.

In their report, the authors outlined their hope for a trail that connected communities, provided recreational opportunities and preserved both the environment and history.

"The Fernleigh Track offers an outstanding opportunity within suburbia to create a living corridor for the interaction of people, vegetation and wildlife within a bushland atmosphere," the authors wrote.

They titled their report, The Fernleigh Track. A Living Corridor.

More reports followed, including an implementation plan for the Fernleigh Track in the late 1990s. Words and plans were gradually turned into construction.

Historian Ed Tonks, who wrote a book in 1988 titled Adamstown via Fernleigh: Trains and Collieries of the Belmont Line, says a few key factors coincided to help make the track a reality.

As Mr Tonks explains, "By the time 1991 came around, there was enough infrastructure left for that railway to be incorporated into a multi-use track". The shoulder of the railway was seen as being too narrow to be sold off for development, as some other former coal lines in the Newcastle area had been.

What's more, this line and the Lambton Colliery had lasted longer than the others did. So, with the times and attitudes to preserving heritage changing, "those who made the decisions were aware of the historical significance of the rail line".

The amalgamation of these factors, Mr Tonks says, "ultimately resulted in the Fernleigh Track".

That, and a whole lot of negotiating, diplomacy and politics. A Fernleigh Track management committee, including Newcastle and Lake Macquarie councillors, staff and community representatives, was formed.

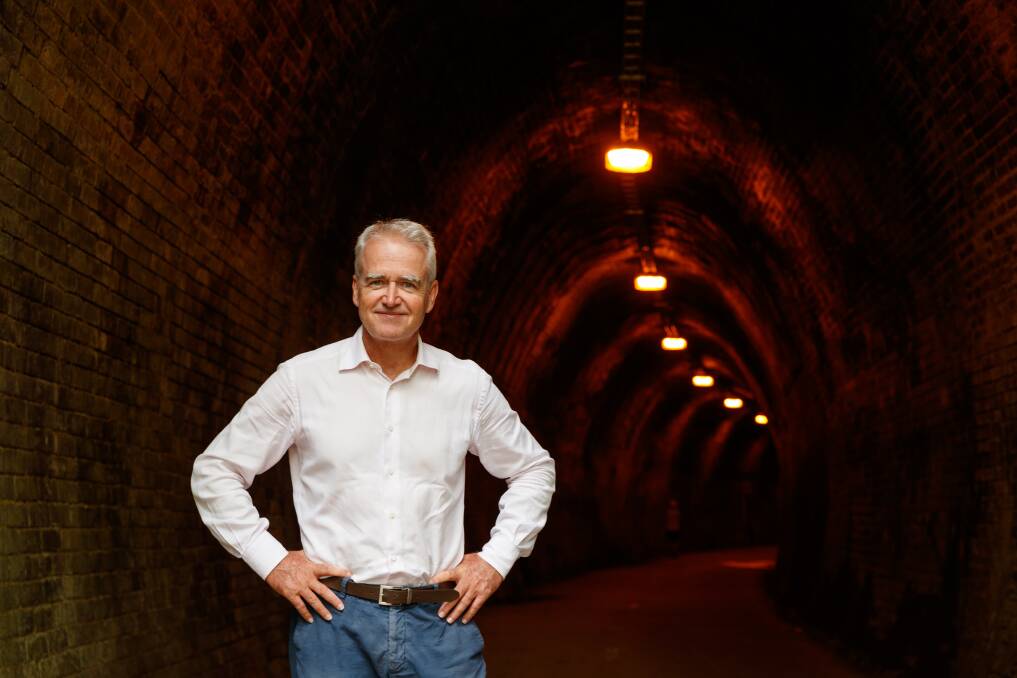

Laurie Coghlan wanted to be part of that committee. He had seen - and heard - the coal trains on the track for years, going to and from the large John Darling Colliery, near his Belmont North home.

"It used to be annoying to sit down for the Sunday night movie, and they'd start loading the coal trains," Mr Coghlan recalls. "I'd have to turn the TV up."

When the trains disappeared in 1988 after the colliery closed, Laurie Coghlan didn't want to see all reminders of the rail line also slipping into history.

"To see that slowly die, it made me want to leave something for the future," he says.

To preserve that heritage, Laurie Coghlan reasoned, the corridor had to be saved.

In a bid to get on the Fernleigh Track committee, he stood as an Independent candidate for Lake Macquarie City Council in 1999. He was elected, and Councillor Coghlan joined the committee, helping bring the Fernleigh Track to life.

The committee faced a host of challenges, but Laurie Coghlan says the biggest was "money, always money".

"And trying to convince people it was a worthwhile project," he recalls.

Between 2003 and 2011, over five stages costing about $11 million, with funding from all three levels of government, the Fernleigh Track between Adamstown and Belmont took shape.

"I never imagined it then, but what I see now is most impressive," says Laurie Coghlan, who was a committee member until he left the council in 2016.

The corridor that once carried the lifeblood of industry was transformed into an artery for the community. The Fernleigh Track helps to get the blood pumping in thousands of walkers, cyclists and joggers each week.

The numbers using the track are large, and they are growing, especially as people seek an escape from the restrictions and uncertainty surrounding COVID.

An electronic sensor installed by Lake Macquarie City Council at Whitebridge has recorded more than 550,000 users since October 2020. So far during the summer of 2021/2022, the sensor has counted more than 66,300 visitors, with a daily average of about 1200. What's more, the council is aware not every track user passes that sensor, so the number is probably higher.

By the recorded usage figures alone, the Fernleigh Track has shifted in little more than a decade from being a neglected scar on the landscape to being a recreational star of the region.

"It represents, and immeasurably adds to, the outdoor lifestyle we have here," Newcastle Cycleways Movement's Sam Reich says.

"The track is a wonderful corridor. Although you are in the suburbs, most of it is surrounded by bush."

So let's explore the track.

Each day over the next week in the Newcastle Herald, we will journey together along the Fernleigh Track.

Along these 15 or so kilometres, you can feel better connected with nature, with the past, with yourself. At the same time, the track allows you to disconnect, to escape, to recharge and - just like the corridor itself - to regenerate.

The old rail line once more is helping people to get somewhere, and to feel even closer to that most elemental of destinations: home.

On Monday, the journey on the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan begins at Belmont. We dive into the Indigenous story behind the area's stunning lagoon, and we wander through wildflowers and the wetlands where mining once ruled.