“It’s easier to weave a sari than set up a loom, especially when you take into account the mathematical and technical precision needed for the latter,” says textile revivalist Pavithra Muddaya while talking about her journey to revive several weaves of Karnataka, including the Cubbonpete Sari.

When Vimor was launched in 1974, the idea was to mentor weavers and give them a livelihood as well as to preserve heritage textiles. “It is imperative for every generation of weavers to see the relevance of innovation in the warp and weft of their work. This is a matter of pride for the weaver, buyer and the designer,” explains Pavithra, who is also Managing Trustee and lead designer of Vimor Handloom Foundation in the city.

Pavithra’s mother, Chimmi Nanjappa, the first manager of the Cauvery Arts and Crafts Emporium in Bengaluru, had gained a comprehensive knowledge of handicrafts and textiles over the years. In 1974, after her husband’s demise, she launched Vimor with Pavithra.

Sustained effort

Pavithra, whose passion led her to open the Vimor Museum of Living Textiles, says, “Sustained effort has gone into nurturing the skill of our weaver-community over the years, and now we are skill-training the next generation. It is this kind of growth that can make them independent and see the industry becoming self-reliant.”

Her success with cotton and silk handloom weavers in Tamil Nadu made Pavithra wonder why the same could not be done for the weavers in Karnataka. “I started with what we call the puja sari. Through research and documentation and confirmation from weavers in Molkalmuru, a district in Chitradurga, we found the puja sari originated in Karnataka, though it is popularly believed to be from Tamil Nadu.”

Particular weave

Pavithra’s association with Molkalmuru started with her father. “He used to travel to Chitradurga and that is where I first saw this particular weave. Annadi Veerabhadrappa, a textile and handloom enthusiast, showed me an award-winning sari and put me to the task of bringing back the weave.”

After this, Pavithra worked with Khana weavers to create a sari. “Through the years, I have worked to revive Chadranchiki (tiny checks on an ilkal sari), Horakere Devarapura check saris and Huvina Hadagale’s khana saris.”

Chimmi, Pavithra’s mother, had a keen eye for aesthetics, according to Pavithra. “If something did not appeal to her, she would say, ‘Even if you were to give it to me for free, I wouldn’t take it’.”

Good rapport

Pavithra says Chimmi had a good rapport with weavers. “Vimor was just starting out then and in order to ensure they had continuous work, she’d put weavers in touch with others such as the Delhi Cottage industries, to enhance their wages. Her empathy was what won the affection of weavers; her example inspires me too. “

The first Cubbonpete Sari Pavithra saw was at an antique store in Hyderabad. “We later acquired one for our collection. In the course of time, I tracked down Puttanna Shetty, a Cubbonpete weaver from the Devanga community. When I showed him the sari, his eyes lit up with child-like excitement as he recollected his grandfather weaving such saris when he was a little boy of eight!”

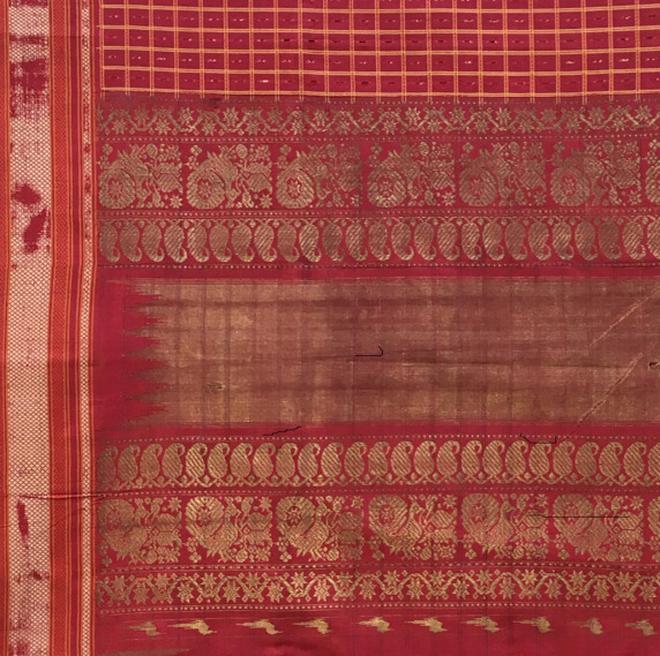

Dense designs

The designs were dense, Pavithra says. “The motifs and composition revealed a technical superiority to ensure the loose threads did not get tangled with bracelets or anklets. The saris didn’t have the typical motifs you see in Kanjivaram saris.

Many people donated their Cubbonpete saris, Pavithra says, which contributed to its revival. “An electrician got me a portion of a sari which had been in his family, while another lady presented me one which had slight differences in the weave. All this gathered knowledge aided in reviving the design aesthetic. When I revived the weave, I had no idea what else to call it but the Cubbonpete sari.”

Interlocking technique

The Cubbonpete sari is woven using korvai (an interlocking technique between the body and the border using three shuttles), says Pavithra. “In this method, the petni (joints of the border) on the sari is beautifully camouflaged and the pallu starts with the body. There is a band of motifs in a three-inch border, usually a gandaberunda (a mythical bird), before the grand pallu begins. Instead of the typical 27-inch pallu, the Cubbonpete sari sports an one of almost a metre and a half.”

The body of the sari has multiple checks in front, while the reverse side reveals stripes. Chemical dyes are usually used in the sari woven in pure silk.

The Vimor Museum of Living Textiles, which opened in 2019, has been growing with the support of donations and textiles from people’s wardrobes, Pavithra says. “It has inspired us to build a knowledge bank of textiles. What makes it a living museum is the fact that these textiles belonged to people of our time, and not from royalty or a bygone era. The fact that our mothers and grandmothers wore these drapes, invokes memories and allows us to draw from shared experiences.”

As Vimor celebrates the 50th year of their association with textiles, handlooms and weavers, Pavithra would like to invite people to help expand the archive. “Look out for the Do Chashme Sari, Paithanis and the Kambli collection in our current collection.”