If you ask those close to Paul Vallas to describe the man behind the headlines of his four-decade career, you’ll get a portrait of a complex figure: one who is an “accessible,” “incredibly honest” visionary, but who can be “impulsive,” and at times a “fish out of water” with a propensity for “temper tantrums.”

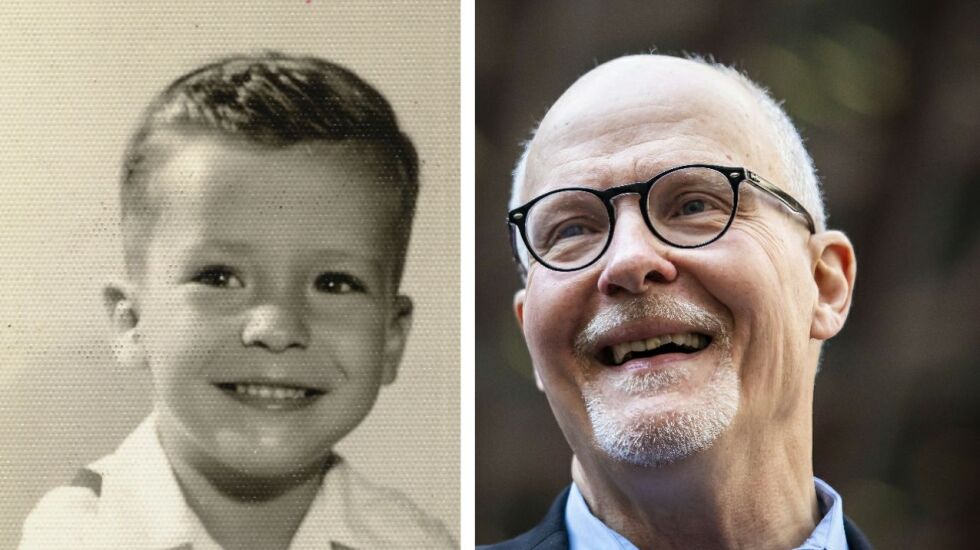

That range of opinion is only fitting for the sometimes controversial figure who has taken a winding path from a shy boy with a severe stutter in the Roseland neighborhood, to the head of Chicago Public Schools — and now the cusp of the fifth floor of City Hall.

Supporters and opponents alike tend to agree on at least a couple of descriptors for the 69-year-old mayoral contender: a “ball of energy” with a deep well of public policy ideas. They also often note a sincere desire to benefit different communities — and a temper that can flare upon others who aren’t up to the task.

“I’ve always been pretty intense and pretty demanding,” Vallas said at his West Loop campaign headquarters during a brief sit-down. “I think I still am — I mean you don’t see me behind the scenes. But I think when I get angry, it’s generally for legitimate reasons.”

After a series of political campaigns that all ended in defeat until Feb. 28, Vallas now finds himself favored by many in the April 4 runoff, where Chicagoans will weigh not only his record, but also his temperament and leadership style when deciding whether he’s fit for Chicago’s highest office.

‘I had my own imaginary friends’

Some of Dean Vallas’ earliest recollections of his older brother were that of a nervous, lanky kid with a speech impediment, who mostly kept his mouth shut to avoid attention.

“There was a lot of bullying going on,” Dean Vallas said. “And he struggled with some of his own learning differences as a result of it.”

The second of four kids, Paul Vallas would play football and baseball with his siblings, but was often more comfortable on his own.

“I had my own imaginary friends,” the mayoral candidate recalled, describing the Flash Gordon-inspired scenarios he’d act out.

It got tougher when the family moved to the southwest suburbs, where Paul Vallas’ father opened a restaurant in Alsip. The persistent stutter, an unfortunate case of acne and a new crowd of classmates at Carl Sandburg High School in Orland Park made for hellish teen years.

“I got into fights a couple of times,” said Paul Vallas, whose grades were middling until he underwent a radical transformation — physically and academically — at Moraine Valley Community College and later Western Illinois University.

“He pretty much locked himself in the weight room and studied all day and lifted all day as well,” the candidate’s brother said. “So he came out four years later, Phi Beta Kappa [honors] from Western Illinois, straight-A student, master’s degree in political science and about 225 pounds of muscle. And he started to build confidence in himself.”

Paul Vallas signed up for the National Guard, where he stayed for 13 years, with hopes of a career as a diplomat. Instead, former state Sen. Sam Maragos, a friend of his parents, pointed Vallas to openings in Springfield, where in 1980 he became an analyst in the Illinois Senate president’s office.

‘It took me about 30 days to basically say, “I own this” ’

A far cry from his days as a shy teen, Paul Vallas has taken a dominant and at times unilateral approach to his leadership roles.

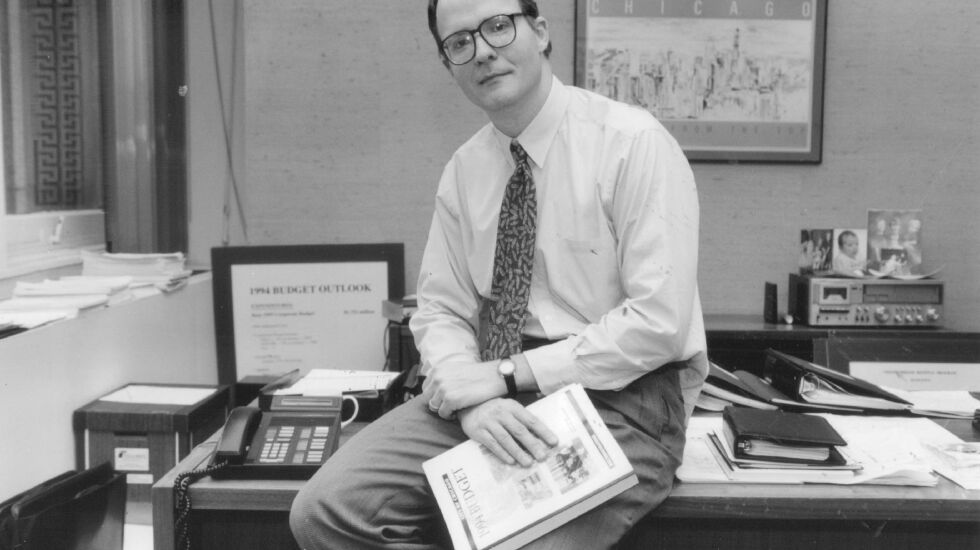

His number-crunching prowess eventually landed him at the top of the Illinois Economic and Fiscal Commission, the nonpartisan agency that did research for the state Legislature. He also caught the attention of Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley, who named him the city’s revenue director in 1990 and later budget director. Daley then tapped Paul Vallas as his first CEO of Chicago Public Schools in 1995, launching his lasting career as a school reformer.

At CPS, Paul Vallas made rapid top-down changes, including opening the city’s first charter schools, an approach strongly opposed by traditional public school advocates in Chicago. He was initially praised for improving test scores and raising teacher pay, and he takes pride today in setting an education agenda he believed in.

“It took me about 30 days to basically say, ‘I own this,’” Paul Vallas said.

But his enthusiasm was at times scattershot, say some former colleagues. The CPS CEO was “all over the place” with ideas, said Carlos Azcoitia — whom Paul Vallas initially fired and then rehired as his deputy education chief.

“He was impulsive in many ways” but “with certain key people, he would listen,” said Azcoitia, who spoke highly of the mayoral candidate.

Paul Vallas also started to develop his now long-standing reputation as an accessible figure who gives his phone number out like candy.

“If there was a problem with the Chicago Public Schools, I felt I should explain what happened,” he says.

Eventually, Daley grew disenchanted with his public schools chief and suspected he was more concerned about his public image than improving the district, Daley confidantes told the Sun-Times at the time.Amid a downturn in test scores, Paul Vallas was pressed to step down.

He stayed in the news with the launch of his first in a series of failed political bids when he ran for governor in 2002 in the Democratic primary. It was a tall task “in the deep end of the political pool,” and Paul Vallas “didn’t have a lot of swimming lessons at the time,” said 42nd Ward Ald. Brendan Reilly, who worked as the candidate’s communications director in that race.

“Paul gravitates toward big challenges,” Reilly said. “He’s a problem-solver. He goes for the really big, nearly impossible tasks.”

Reilly, who has endorsed Paul Vallas this year and described him as “a bit wonkish” and “incredibly honest,” said he’d at times have to confiscate the candidate’s phone to stop him from talking to reporters ad nauseam about his policy ideas. Paul Vallas lost that primary by 2 percentage points.

‘Not a punitive person’

With a brewing reputation as a “fixer” — for better or worse — Paul Vallas took his school overhaul formula on the road in 2002 with a series of school district stops including in Philadelphia, Louisiana, Haiti and Chile. It’s work his supporters cite as evidence he can face a challenge head-on, even when he made missteps.

“Was he aggressive? Yes. Did he cuss a lot? Yes,” said Joyce Kenner, the former Whitney Young Magnet High School principal, who has endorsed him. “Paul Vallas has made mistakes. But has he learned from those mistakes? Absolutely.”

His temper is among the things New Orleans public school advocate and parent Karran Harper Royal remembers most about Paul Vallas. Harper Royal said she would meet with him to advocate for a school in her neighborhood, which ended up being run by three different charter companies, despite protests.

“He told me everything I wanted to hear. … He was friendly until you pushed back on what he was doing,” Harper Royal recalled. “And then he acted like a 2-year-old. I have seen him slam things on the desk.”

The mayoral candidate admits he still loses his temper but does so “behind closed doors,” adding that he’s “not a punitive person” and “can take a punch.”

While away, Paul Vallas would make regular trips back to visit his wife Sharon and sons Paul, Gus and Mark. He saw an opportunity to come home in the 2010 race for Cook County Board president, and thought about running as a Republican. Though he never ran at all, that he considered a GOP ticket haunts him now as some question his true party leanings.

Paul Vallas makes friends across the political spectrum, Dean Vallas countered, adding that his brother — a film buff — used to go to the movies with an unlikely cast of characters, including the Rev. Michael Pfleger and the late former Republican Attorney General Jim Ryan. It’s a bipartisan approach Vallas honed in Springfield, Dean Vallas said.

“He’d walk up to a Republican farmer from Bloomington and say, ‘Hey, here’s what a farmer in a very similar district is doing in Iowa. Take a look at this.’ ” Dean Vallas said. “And he would do the same thing for a legislator from the Back of the Yards. So it’s always been about policy.”

‘A fish out of water’

It was Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner who appointed Paul Vallas to his most recent post on a public payroll, tapping him in 2017 for a seat on the Chicago State University board of trustees, hoping for a turnaround of the financially maligned South Side campus.

His work there earned mixed reviews.

“He was almost like a fish out of water,” said the Rev. Marshall Hatch Sr., who chaired the board when Paul Vallas arrived, and has endorsed his opponent Brandon Johnson for the runoff. “He’s this ball of energy guy, and his brain is all over the place.”

“He’s calling the university ‘the district’ — I mean, that’s kind of like a dead giveaway. He’s not entirely clear that this is a different context.”

But retired professor Robert Bionaz, who was president of the faculty union at the time, has a different impression.

“Sometimes [Vallas] got the nomenclature wrong, but I think he had a good understanding of the educational mission.”

He recalls Paul Vallas reaching out to him to discuss campus issues — a “highly unusual” olive branch.

“I thought it was a mistake that they didn’t give him more authority,” Bionaz said.

Paul Vallas was out after barely a year, with some board members questioning whether he’d used the post to score political points ahead of his first run for mayor in 2019, which the candidate disputes.

Tragedy struck the Vallas family in 2018, when the candidate’s son Mark died in California after a struggle with opioid addiction.

Paul Vallas told the GreekReporter news service at the time that his son’s death “made me more determined to run for public office.”

‘He’s been better than I’ve ever seen’

After placing ninth in a crowded field in 2019, Vallas has found his groove this election, in part through his focus on the city’s persistent crime problems, and his ability to rein in his wonkiness.

“We never needed a policy team. What we need is people to write down what he’s saying, and then condense it … He’s been better than I’ve ever seen,” said Dean Vallas, who added that his brother is much more willing to attack his opponent this campaign.

“We have two weeks left,” Paul Vallas said in an interview Monday. “The last two weeks are going to be like a slugfest, like the 14th and 15th rounds of a heavyweight boxing match. So if you’re gonna win on points, you’ve got to win the final two rounds.”

Mariah Woelfel covers city politics and government for WBEZ. Mitchell Armentrout covers casinos, gambling and other political issues for the Chicago Sun-Times