Paul Rudolph wrote in 1952: ‘One doubts that a poem was ever written to a flat-roofed building silhouetted against the setting sun.' Then 34 years old, the Kentucky native had only just established his architectural practice but had already identified what he would devote his life not merely to avoiding but to avenging: the obvious and the empty, visual stasis, that which provokes nothing but indifference. He charted his own course: modernist architecture, but with feeling.

Step inside The Met’s Paul Rudolph exhibition

Rudolph’s open, ambitious, and vital approach to designing everything 'from Christmas lights to megastructures', as he once put it, succeeded in eliciting strong reactions – odes and screeds that oscillated with the currents of architectural thought – and continues to do so, 27 years after his death, as New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art surveys his shape-shifting and summary-defying yet stunningly cohesive career in the first major exhibition dedicated to Rudolph. The show also marks the Met’s first major exhibition of 20th-century architecture in more than five decades.

Nimbly curated by Abraham Thomas and accompanied by a clear-eyed catalogue designed by Michael Dyer, ‘Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph’ brings together more than 80 large-scale drawings (most never before exhibited), models, furniture, material samples, and photographs. The exhibition is organised thematically around key areas of interest for Rudolph, starting with a view of his atelier-style New York architectural office of the early 1960s and then darting back and forth across time, scale, and material. Here are the robust and craggy Asia projects of his late career, as well as the formative residential work in mid-century Florida, where he pioneered the Sarasota Modern style in partnership with Ralph Twitchell.

Richly detailed renderings are complemented by a compilation of film clips featuring Rudolph buildings, including Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums (filmed at Beekman Place, Rudolph’s legendary Manhattan home-cum-laboratory of ideas) and the 1983 sci-fi thriller Brainstorm, starring Christopher Walken, Natalie Wood, and the sloping concrete walls of the now-demolished Burroughs Wellcome headquarters in North Carolina. 'Knowing the drama you have within Rudolph’s drawings, I wanted to give a sense of what it’s like to move through a Rudolph space,' said Thomas on the show’s opening day. 'Many of these films offer rare moments of seeing spaces that no longer exist.'

The dynamic exhibition design invites viewers to draw connections and discern influences as they bubble up and coalesce into signatures. Among the most fascinating forces to consider are the balance of thrusting and counter-thrusting space mastered by Frank Lloyd Wright (whose buildings Rudolph described as 'beyond analysis… so magical'), the power and playfulness of Le Corbusier, Rudolph’s education at the Harvard Graduate School of Design under Walter Gropius, and his three-year stint in the Navy during the Second World War that doubled as a masterclass in industrial materials and prefabrication.

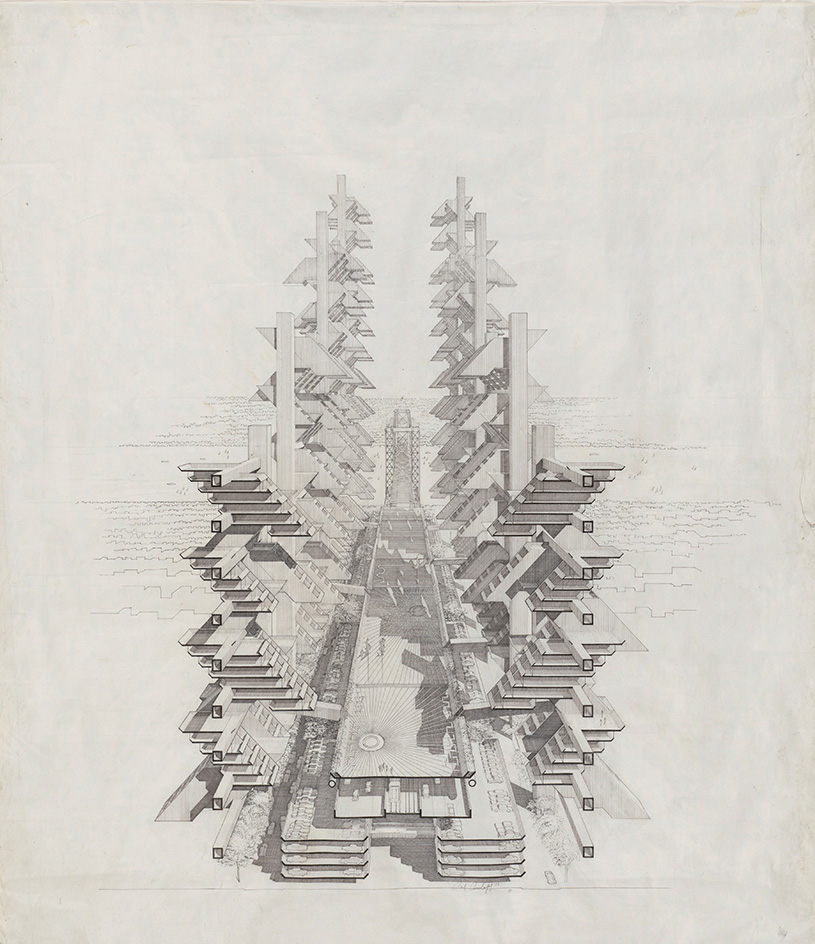

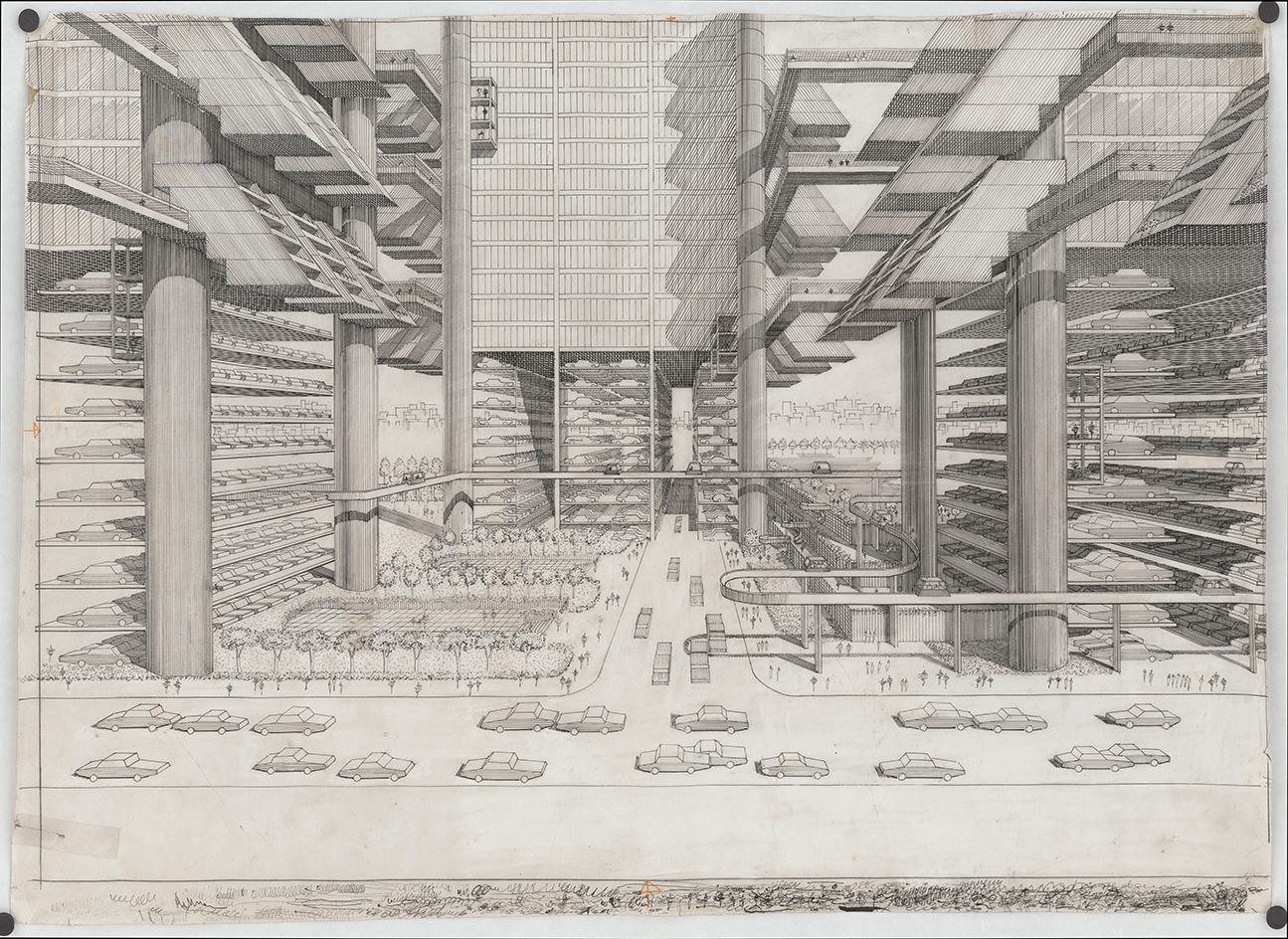

Looming large is the 'megastructure', a typology informed by Rudolph’s interest in the potential of modularity as a catalyst for finely calibrated comprehensiveness. Monumentality in context. Subtlety that could swoop and soar. What at first glance appears to be one-size-fits-all bombast soon reveals its lyrical specificity, as in his unrealised Lower Manhattan Expressway project (circa 1967–72), commissioned by the Ford Foundation as a response to the foiled scheme of Robert Moses.

While Rudolph summarised his approach as 'a building two miles long', his proposal was more nuanced. It called for carving out a subterranean thruway and erecting atop it 'a network of buildings which are related to what is already there so that the pedestrian flow above ground is not interrupted by the needs of the traffic below'.

Rudolph was a stickler for site, which, along with considerations of space, scale, structure, function, and spirit, represented for him 'the essences of architecture'. He established these six principles for his own use in 1952, and keen attention to each one is reflected in his acclaimed Art and Architecture Building at Yale University, where in 1958 he was appointed chairman of the Department of Architecture. 'It was the Guggenheim Bilbao of its time,' said architectural critic Paul Goldberger in a 2018 talk on the occasion of Rudolph’s centennial. 'What you feel is the instinct to respond to old texture with new texture, not the absence of texture. To respond to old richness with new richness rather than with austerity.'

Rudolph textured the A & A Building with corrugated concrete, moulded into vertically ridged panels with wooden forms like the one included in the exhibition and then bush-hammered to expose the stones and seashells and flecks of mica within. Call it soulful, shimmering brutalist architecture.

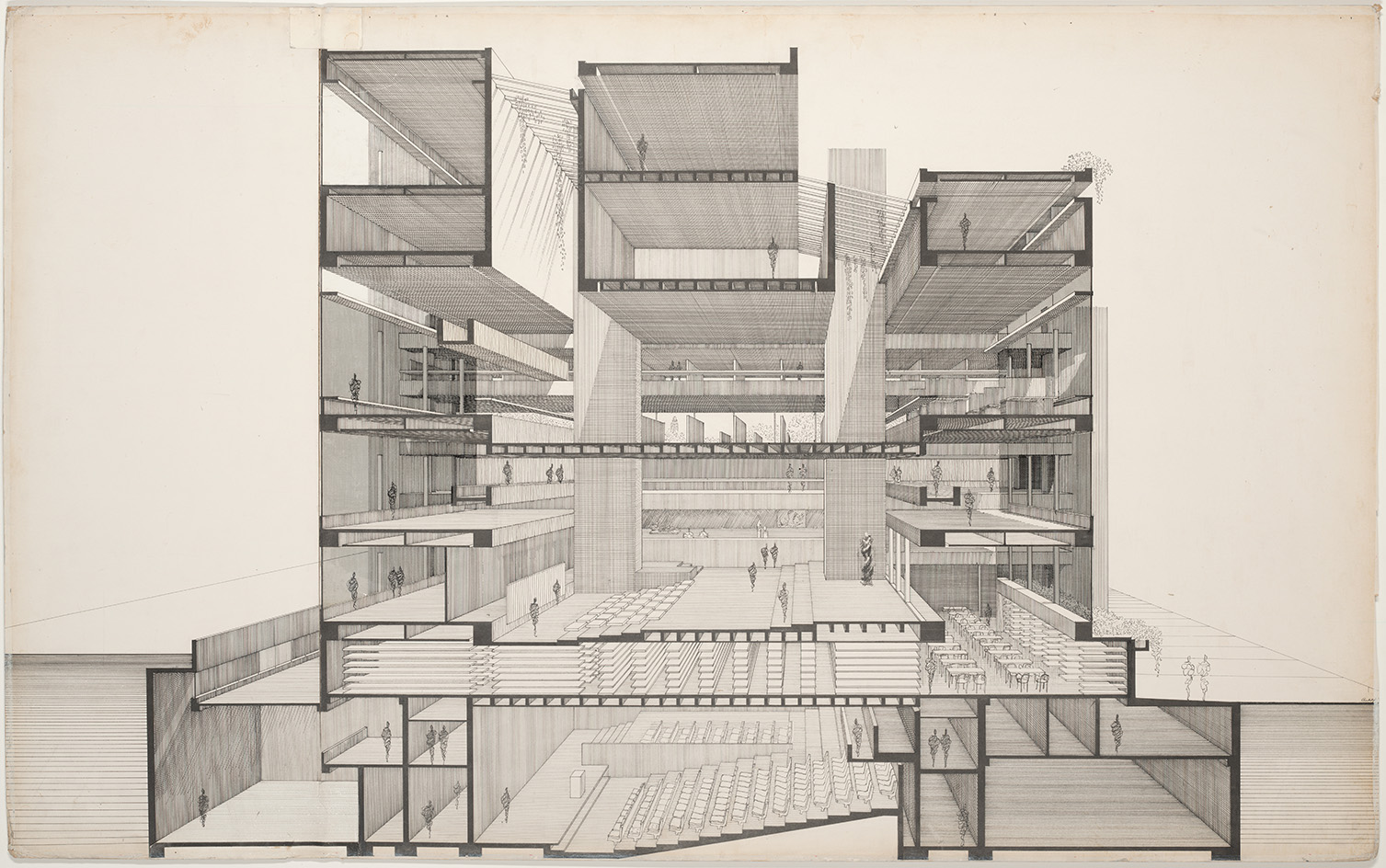

His iconic perspective section drawing reveals the building’s pinwheel of 37 exquisitely balanced levels across 9 floors, for which he masterminded elements ranging from a canvas curtain painted by Willem de Kooning and Beaux-Arts plaster casts of ancient reliefs to carpeting in a distinctive paprika hue that punctuates the Met exhibition.

The show culminates with an exploration of 'experimental interiors', including Beekman Place and the remodelled carriage house on East 63rd Street where Halston lived from 1974 to 1989. The exhibition pairs the fashion designer’s early Warhol canvas (1961’s 'Before and After I', a salute to found imagery and aesthetic transformation) with Rudolph’s Rolling Chair of 1968 (Lucite panels, chrome tubes, swivel casters, a hint of Hannibal Lecter).

A plaster-cast architectural morsel by Louis Sullivan that Rudolph displayed at Yale and at home is a reminder of his commitment to history as well as the new. 'Rudolph understood history as well as any post-modernist and integrated it into his work as subtly as [Louis] Kahn,' Goldberger has said. 'He somehow never got credit for this.'

'Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph' runs through 16 March 2025