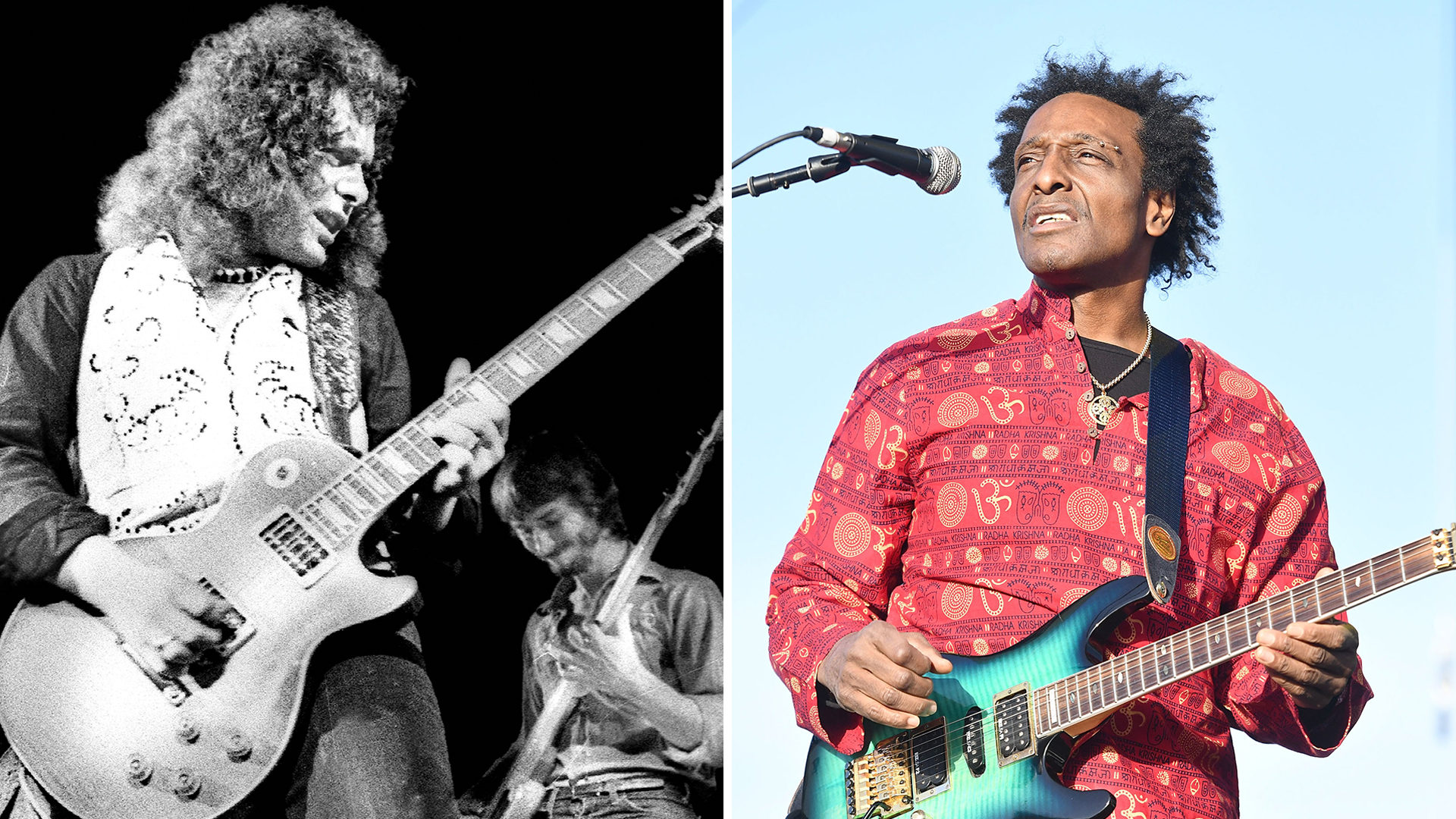

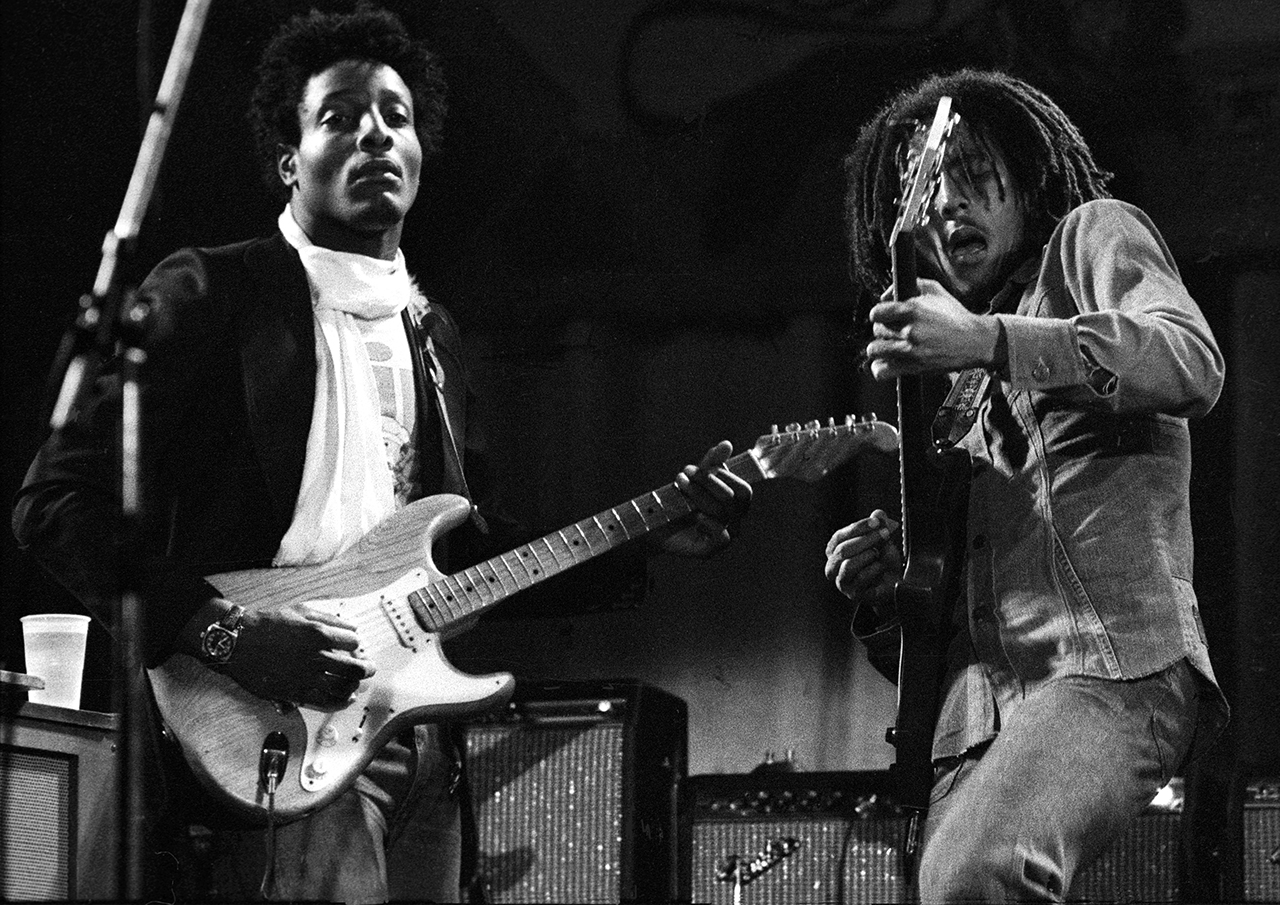

Former Bob Marley and the Wailers guitarist Al Anderson – the man behind the emotive, singable solo on the classic live version of No Woman No Cry – is well-known for sharing memories from throughout his storied career via his Facebook page.

Between extensive tour dates where he celebrates the musical legacy he helped to shape, and while he’s creating new music with the Original Wailers, Anderson generously offers eyewitness accounts of flanking Marley, Peter Tosh and others, onstage and in the studio.

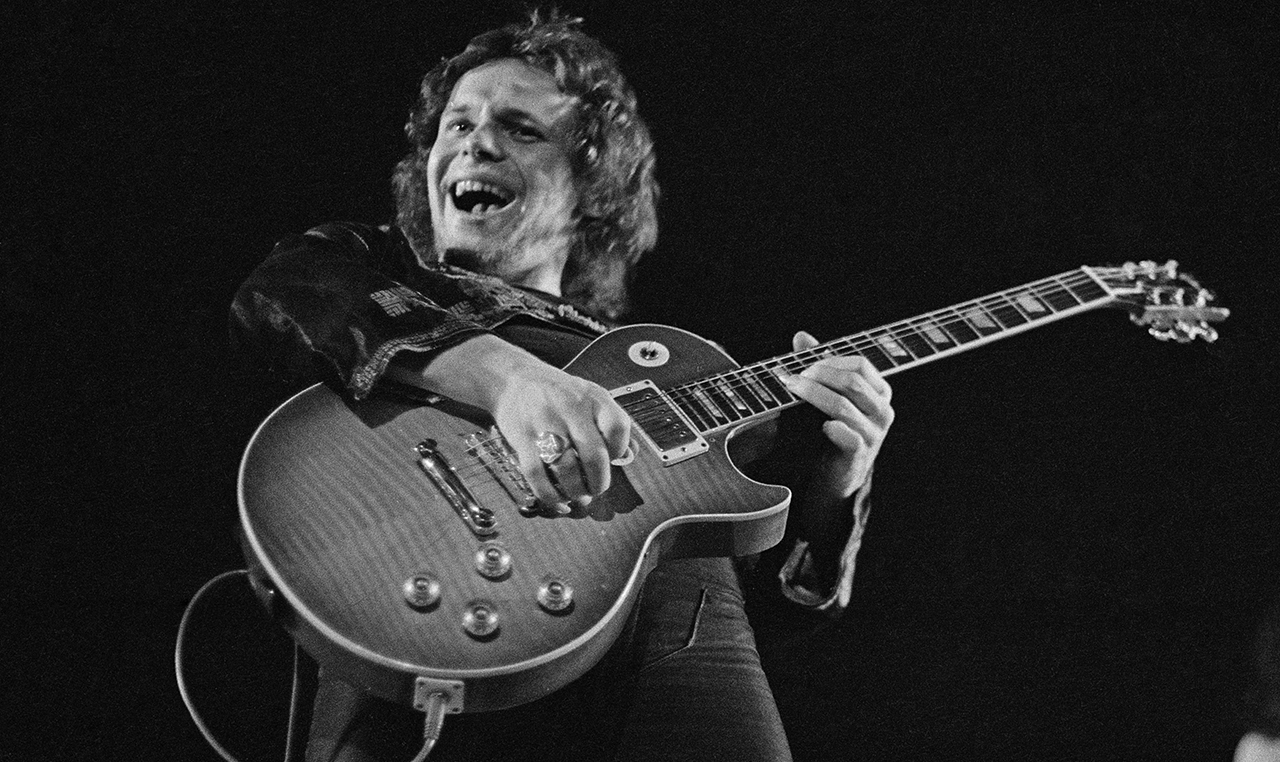

Earlier this year he revealed that his introduction to the Wailers – and to roots reggae – had come from a source so unexpected that Guitar World needed to find out more. Because while Anderson was familiar with early reggae pioneer Jimmy Cliff, he wound up in the Wailers’ world via Free guitarist Paul Kossoff.

The pair met shortly after Anderson relocated from Montclair, New Jersey to London, England in 1970. The move had come about after an encounter with Chris Blackwell, owner of Island Records – to which Free were signed – when Traffic had played at New York’s Filmore East. Blackwell offered Anderson’s band Shatkatu a deal, hence the transatlantic trip, and Traffic’s Chris Wood steered Anderson towards Kossoff.

“Paul was exceptionally kind to me,” Anderson says. “I used to go over his house all the time. He had the best guitar collection I had ever seen! He had everything – ‘50s and ‘60s Strats, SGs, Marshall Majors, 50-watts, small box 100-watt Plexi, Orange. He had such knowledge of vintage guitars back in the early 70s. He knew what they would be worth in the future.”

One night at Kossoff’s place, a phone call changed Anderson’s life. “It was Chris Blackwell, asking Paul to come and do a session,” he recalls. “Paul goes, ‘I’m not really in the mood.’ He'd been drinking pretty heavily – but I was pretty sober. He said, ‘I have an American friend here who can cut it.’ So they sent me a minicab.”

While they waited, Kossoff gave Anderson a crash course in reggae. “I’d never heard Bob. Paul played Catch A Fire and Burnin’ for me. I was like, ‘Wow, this is interesting – I don't know where beat one is!’ So Paul counts, ‘And one, two, three, four,’ and hipped me.”

One cab ride later, Anderson arrived at Island Studios, where the recording of Marley classic Natty Dread (1974) was in progress.

“I had a Clyde McCoy wah wah, ‘57 Blonde Strat and a Twin Reverb,” he remembers. “I walked straight in the studio. Chris said, ‘This is Bob. Let’s go to work.’ I didn’t get a chance to meet him until after we did a couple of couple of takes!”

Thrown in at the deep end, those initial takes were rejected; but Anderson’s remarkable versatility meant he soon adapted to Marley’s requirements.

“I was playing jazz rock on top of reggae, and it wasn’t there. They didn't like it so much. I said, ‘OK, give me an opportunity to hear some more tracks.’

“After the third or fourth track I said, ‘I know exactly what they want.’ It had a country feel to it, simple 1-4-5 chord structure. I said, ‘Just run the track. We’ll make it happen.’”

Bob was really happy that he was completing the album with the guitar sound he had in his head

As the tape rolled, he laid down solos on No Woman No Cry, Them Belly Full (But We Hungry) and Rebel Music (3 O’Clock Roadblock) in rapid succession. He remembers he “did the whole record in about 45 minutes,” adding: “I went into the control room. They were elated, so happy. ‘It’s exactly what we were looking for. You got the sound. You tagged it!’”

Job done, Anderson returned to Kossoff’s place. “He said, ‘What was it like?’ I said, ‘He had a lot of hair!’”

He says of Marley: “Bob was very quiet and cool. He had a spliff in his hand, and he was really happy that he was completing the album with the guitar sound he had in his head.”

Shortly thereafter, Anderson received a phone call from Island Records. “They said I should come down and have a conversation about joining Bob Marley and the Wailers. I got the deal – ended up flying to Kingston, where Bob met me and tried to get me into the Jamaican state of mind.”

Tragically, as Anderson’s star was in the ascendent, Kossoff’s battle with addiction continued to weaken his health, precipitating his death at the age of 25 in March 1976. Today, Anderson is keen for his late friend to be remembered in a good light.

“I owe everything to that guy,” he states. “He was a wonderful, wonderful brother. I'm just sorry he’s not around so I can thank him for all that he’s done for me. If it wasn’t for Paul Kossoff, I could be working at McDonald’s now.”

- Check out the Original Wailers’ upcoming tour dates.