Should the National Gallery of Australia be staging a major Paul Gauguin exhibition?

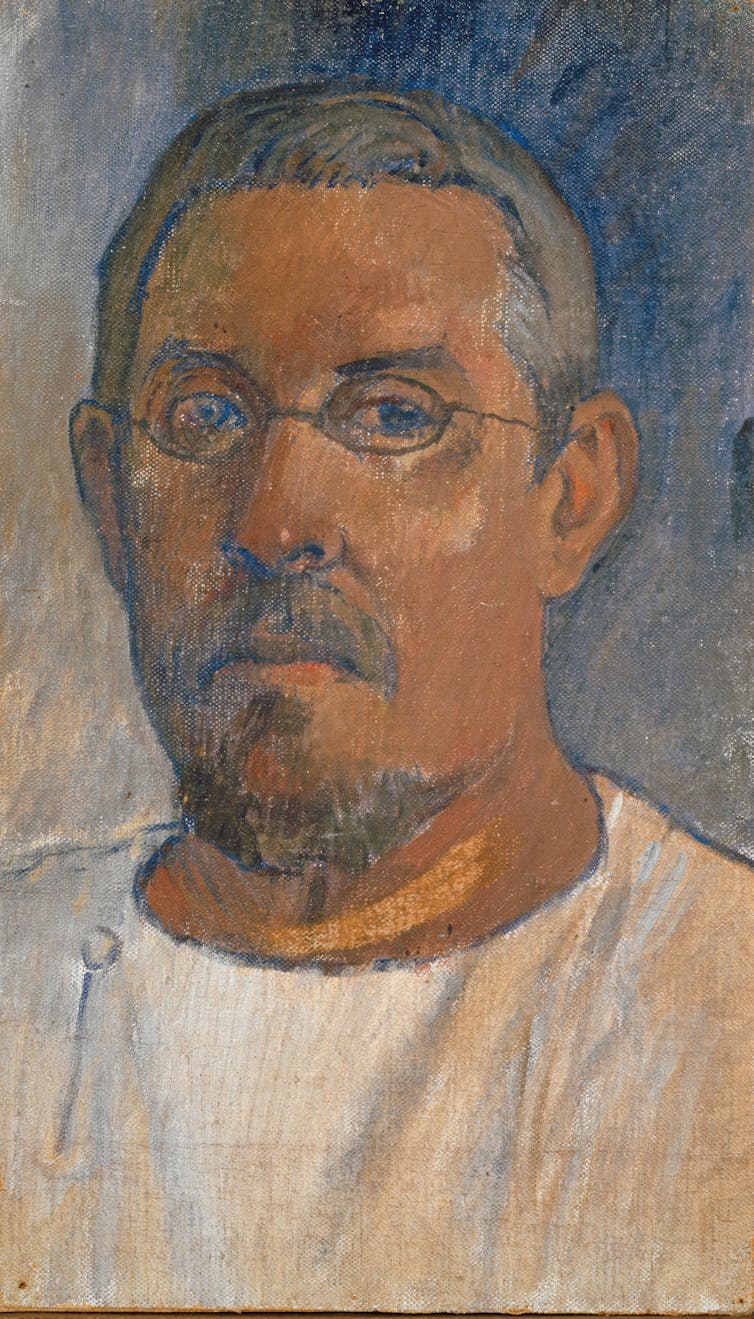

At first glance, the question may appear a little strange. Gauguin (1848-1903) is a hugely significant figure in most European constructs of modern art and a key artist in any discussion of French neo-primitivism, post-impressionism and symbolism. His paintings at auction realise staggering sums of money: in 2022 one changed hands for more than US$105 million.

But the ethical case against Gauguin is that he was a violent, fist-swinging thug, a paedophile and a serial rapist.

Painting a violent fantasy

Gauguin was a “sex tourist”, who dumped his wife and five children in poverty in Europe and took up residence in French Polynesia, where he married three native children, the youngest 13, the others 14.

He had numerous children with them and infected some of them with syphilis, before he died aged 54. These “child brides” served as models in many of his paintings that took the form of exotic, erotic fantasies.

Curator and art historian Ashley Remer sums up the case against Gauguin:

From a museum perspective, choosing to showcase men like Gauguin does, in its own way, support rape culture […] [Gauguin] purposefully and consistently made the choice to exploit and assault young girls.

The English art critic Alistair Sooke bluntly describes him as a “19th-Century Harvey Weinstein”.

Gauguin wrote of his Tahitian women that she:

lives almost as do animals […] like she-cats, she bites when in heat and claws as if coition were painful. She asks to be raped. […] Giving her a good beating every week [makes her] obey a little. She thinks very poorly of the lover who does not beat her.

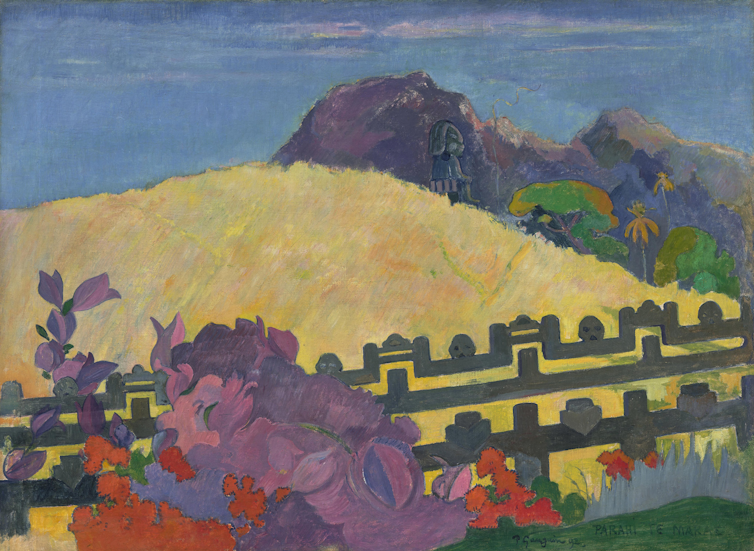

Many of his paintings create a fantasy world of a “primitive” Polynesia he really neither saw nor experienced, but imagined, with scantily clad submissive very young girls in exotic native huts with pagan deities in the background, which he copied from photographs of gods from India and Indonesia.

For Gauguin, the missionaries had already spoilt Polynesia by the time he arrived in June 1891. Most women he encountered were fully clad and some engaged with modern life. He created his fake erotic exotica as a personal quest and for the European viewer’s delectation.

Ethical responsibility

Is the correct course of action for a public art gallery to exhibit and celebrate Gauguin’s work, while highlighting the fact he was a seriously flawed human being?

Or is this to quietly condone domestic violence and paedophilia, on the condition that the participants say “three Hail Marys” after seeing the show?

I do not know the answer to this question, but feel uncomfortable in an atmosphere where so much dismay is expressed concerning domestic violence in Australia to be simultaneously celebrating an artist for whom violence against women was part of his everyday life.

The idea of ethical responsibility for art institutions may not be new, but today it is a rapidly expanding concept.

The traditional questions of legal provenance have been joined by questions concerning gender equity and, increasingly, the investigation of the moral character of the artist.

Dennis Nona, for example, was once the most widely exhibited Torres Strait Islander artist in Australia. But once he was sentenced to jail for sexual assault, the National Gallery in Canberra – along with most public art galleries in Australia – removed every work of his from display.

It could be argued Nona’s art in no way reflected the crimes for which he was convicted. In the case of Gauguin, his criminal lifestyle lies at the very core of his art.

Tahiti to Australia

The National Gallery’s exhibition boasts to be the largest Gauguin exhibition to be shown in Australia – over 140 works drawn from 65 private and public collections worldwide.

The curator, Henri Loyrette, has assembled Gauguin’s paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures, ceramics and decorative arts, together with cultural items from the Musée de Tahiti et des Îles.

The main idea was to bring Gauguin’s vision of Tahiti to Australia and, along the way, glance at Gauguin’s journey from his early Impressionist-inspired work through to his late Polynesian pieces. After Canberra, the exhibition will travel to the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas.

It is an exhibition where you may despise the artist, yet invariably admire the formal properties of his art. Gauguin was a brilliant colourist, an exceptional draughtsman and had that rare ability to reinvent the medium with which he engaged. This applied to his remarkable carvings in wood, his reimagining of the potential of the woodcut and of course his late, colour-saturated, sun-drenched images of French Polynesia.

For a contemporary viewer, his paintings in this exhibition, including Tahitian women (1891), Three Tahitians (1899) and Te faaturuma (the brooding woman) (1891), reflect an ideology and lifestyle as inappropriate 121 years ago, when Gauguin died, as it is today.

London’s Tate Modern held its major Gauguin retrospective 14 years ago. As I recall, it was a standing-room-only affair that broke all sorts of attendance records.

The National Gallery exhibition is much more modest in scope and is supplemented by the spirited SaVĀge K’lub installation that addresses issues in Polynesian culture.

It will be interesting to see how contemporary Australian audiences respond.

Gauguin’s World: Tōna Iho, Tōna Ao is at the National Gallery of Australia until October 7.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

The National Sexual Assault, Family and Domestic Violence Counselling Line – 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) – is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week for any Australian who has experienced, or is at risk of, family and domestic violence and/or sexual assault.

Sasha Grishin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.