You can tell that something genuinely remarkable is happening, just from Colin Hendry’s face. The rugged Scotland centre-back always had a distinctive look – fierce Highland warrior with the face of an old Russian woman – but suddenly that stoic frame crumples with confusion.

Against the run of play, a supposedly portly and past-it Paul Gascoigne lifts the ball into a perfect orbit over Hendry’s head, sprints like a naughty kid and prepares to apply the coup de grace.

It wasn’t supposed to happen; according to a number of newspapers, Gascoigne shouldn’t even have been part of the England squad. A Mirror survey suggested that 86 per cent of readers wanted him expelled from Euro 96, after the Three Lions’ boozy warm-up antics in Hong Kong.

It’s now widely forgotten that he had been in consistently superb club form during 1995/96, but no matter: that bewitching move against Scotland turned popular opinion on its head.

Two days later, the Mirror famously published a public climbdown: “To Mr Paul Gascoigne: an Apology,” conceding the “fat, drunken imbecile” was now his country’s saviour. Again. But then Euro 96 summed up the player’s international career: heavy scepticism, followed by breathtaking brilliance and a climatic, agonising near-miss.

“He was a bunch of contradictions,” explains journalist Henry Winter, who devoted a whole chapter to the midfielder in 2016 book, 50 Years of Hurt. “I’ve always thought that Shakespeare – without going too Alan Partridge here – would have had an absolute field day with Gascoigne.”

Despite his well-documented (or, more accurately, badly documented) off-stage exploits, Gascoigne is arguably England’s most popular player ever. He is Gazza. Today we tend to view that story as more tragedy than comedy, but he packed more joy and drama into 57 appearances than umpteen golden generation centurions put together.

His is a tale of three major tournaments – one of which he didn’t even reach in the end – and his impact transcended the game. He might just have changed the world, a bit.

The game-changer: Italia 90

According to Mark Perryman – the notable England follower, author and Philosophy Football co-founder – pretty much the whole modern game is down to Gascoigne. Including this magazine, perhaps, which launched in 1994. Italia 90 changed everything.

“The Premier League and the Champions League were both formed in 1992 – neither would have happened if it wasn’t for Gascoigne,” he tells FFT. “Gascoigne as an individual in the England team proved – not only to the FA, but to sponsors and broadcasters – that despite an incredibly dark period in the ’80s, football had the potential to reach parts of the English population that no one else could.”

Gazzamania was fairly extraordinary, and unprecedented as well. Chat royalty Terry Wogan introduced him as “probably the most popular man in Britain today” in September 1990, before worrying for his welfare. The drunk George Best interview on his show happened that same month.

Hype aside, one reason for Gazza’s appeal is that his career was geared towards the national team. Fellow North East native Gary Pallister played behind the Gateshead-born midfielder for England B, the full squad and then eventually Middlesbrough, and reckons he was destined to replace England’s previous generation.

“The kid was an absolute genius,” Pallister recalls to FFT. “Bryan Robson told me that the only time he got the hairdryer off Alex Ferguson was the first time United played against Gazza at St James’ Park: ‘Any chance of you getting closer to him?’ He gave him a torrid time – I don’t think he’d ever seen a talent like him. And for a guy like Bryan Robson to say that…”

The ‘new Bryan Robson’ idea would actually be Fergie’s sales pitch in the summer of ’88, after Newcastle’s lack of ambition caused discontent. However, Tottenham boss Terry Venables gazumped him by promising to get Gazza into the national team. And he did, although England were unsure for a long time. The regular refuelling was an early worry.

Legendary writer and Three Lions insider Norman Giller is a long-time Spurs and Gascoigne fan. Giller’s best mate Jimmy Greaves – a previous England maverick who scored 44 goals in 57 games – had a hand in an early Gazza phenomenon: chocolate missiles. They would watch ITV’s live feed together on Saturdays.

“Paul was already making a name for himself at St James’ Park with some astonishing ball control,” remembers Giller. “But you couldn’t help noticing that he looked a bit overweight. Jimmy used to start referring to him on screen as ‘Fat Boy’ and the ‘Mars Bar Kid’, but rather than get annoyed, Gazza played up to it.”

He would often bite on a lobbed Mars Bar for a laugh, although that was another concern.

“It quickly got around that Gazza had special talent,” continues Giller. “I remember Dave Sexton telling me after he selected him for England Under-21s: ‘Paul’s got the best ball control of any British footballer I’ve seen since George Best, but I think he plays to the gallery too much. I’ve recommended him to Bobby Robson for the senior team, but he needs to be told he’s a professional footballer, not a circus clown’.”

The 1990 World Cup seemed a long way off. Gascoigne’s first taste of tournament action was Toulon with the under-21s in 1987: he needed a couple of pre-flight brandies, and the physio to hold his hand during it. England finished fifth.

Gascoigne also underwhelmed at Spurs initially. Then-youth team midfielder Jeff Minton was a Gazza protégé, and would also feature in his last great game. “When he first came to Tottenham he was quite chubby,” recalls Minton. “But that was his thing: great body strength. He’d use his arms and you couldn’t get near him.”

England always seemed wary of mercurial midfielders – Bobby Robson had dropped Glenn Hoddle in favour of the more predictable Neil Webb – but were then totally outclassed at Euro 88.

English clubs’ post-Heysel ban from Europe was blamed, but new ideas were needed. Enter Gazza, who made his debut against Denmark that September. He didn’t shine straight away, but quickly made a mark off the pitch. Fellow newcomer Paul Parker got an early taste of the jovial Geordie’s anti-boredom antics in an Albanian hotel.

“He was breaking up bits of soap and chucking it at chickens,” explains Parker. “Then he started throwing little lapel badges – a handful at some guy on a bike, then other people dived for them and I think the rider cut his head. Then Bobby Robson came in, looked down and started to laugh. Because it was Gazza.”

Gascoigne’s oddly candid autobiography is awash with eyebrow-raising tales. At Italia 90 alone he confesses to almost crashing the team plane, yanking Gary Lineker’s wife off a boat and starting the hotel room larks that forced Bryan Robson home injured – a novel way to pass the torch. The 23 year old belatedly made the squad thanks to an inspired display against Czechoslovakia, but England’s dour group stage opener with the Republic of Ireland quelled thoughts of a skilful new dawn.

The national mood swing began against the Netherlands, who stuffed Bobby Robson’s charges at Euro 88 en route to glory. But with one Ronald Koeman-baffling Cruyff turn, Gazza rubbished the notion that England were backwards luddites. He then set up the winners against Egypt and Belgium, was reckless but redeemed against Cameroon in the last eight – conceding then creating penalties – and the Three Lions were unlikely semi-finalists.

Gazza was playmaker and chief cheerleader: when Paul Parker deflected in West Germany’s opener, then delivered the cross for Lineker’s equaliser, guess who was first with the hugs.

“Gazza was such an emotional guy,” reveals Parker. “I think that game just meant so much to him. He wanted to win everything – a tackle, or if he took someone on he had to beat them. But he got frustrated if things didn’t go his way.”

Indeed, he would soon be in tears after a tournament-curtailing yellow card, while a nation wept with him. Gascoigne was supremely relatable.

“The morning of the World Cup semi-final, a front-page headline read, ‘There will be war in Turin tonight’,” says Mark Perryman. “The media has changed a lot now, and obviously Gazza is a massive part of that. Today we’re a bit more tuned into different versions of masculinity.”

Times writer Alyson Rudd was also a groundbreaker, as a high-profile female sports journalist in the early-90s. She isn’t Gazza’s No.1 fan, but has previously written about his impact; the tears in particular. Overnight, a whole new demographic – particularly women – viewed footballers in a different light.

“I think people who didn’t watch much football just saw something that was…lovely,” she tells FFT. “I do have vague memories of some of my relatives saying, ‘Why is it so important, why is he crying?’ Once they know what’s going on, they think, ‘Oh, I’ll definitely watch the next game’. It’s a soap opera.” But would Gazza be the hero or villain?

Boobs, knees and balls-ups: 1990-95

There’s a telling sentiment in Gascoigne’s book, My Story, after the tears. “I didn’t want to go home,” he sighs. “I wanted to stay in Italy, playing in the World Cup forever.”

Home would become increasingly traumatic, but at least the welcome was warm. Gascoigne received a suitably Beatles-like reception at Luton Airport (he’s named after Paul McCartney, after all), but would eventually wonder if the infamous bus-top fake boobs were thrust at him by a newspaper rather than an admirer.

He initially revelled in Gazzamania – lucrative records, books and endorsements – but regretted his tabloid newspaper column. It irked their competitors and “even The Sun weren’t always nice to me, either”.

Early-90s Fleet Street, says Henry Winter, “was in a brutal circulation war, particularly between The Sun and the Mirror. You would almost have two people on each paper, one pro-Gazza and one against. But everyone knew that he was box office.”

New England manager Graham Taylor wasn’t convinced, however, and sensationally dropped Gascoigne against Ireland ('it happened to a few of us', admits a still-sore Paul Parker). As Glenn Hoddle later discovered, keeping Gazza on the sidelines was troublesome. Bryan Robson would coach him at Euro 96, then manage him for Middlesbrough.

“In terms of looking after Gazza on the training pitch, it was easy,” he tells FFT. “He just loved playing football; training sessions and the games. The hardest thing was trying to keep him calm, and stopping him making any rash decisions which could get him injured.”

That all-or-nothing exuberance would ultimately derail his career. In 1991, Spurs were skint and desperate for a good cup run; Gascoigne was struggling with injuries, but perennially keen.

“He’d train with the first team and then come and train with us,” says youth team-mate Minton. “He was really hyped up a few days before the FA Cup final. It was mental, and that spilled over into the game – all the over-enthusiasm caused his knee injury.”

The cup-final cruciate ligament injury – followed by a pub-fight relapse – ruled him out for 16 months. And yet Lazio still spent a British transfer record £5.5 million on him in 1992. He was box office – and it cast a huge shadow over Taylor’s struggling England side.

Gascoigne missed an anaemic Euro 92, but qualification for the 1994 World Cup began promisingly. He excelled as England surged 2-0 ahead against the Dutch, but then Jan Wouters’ elbow fractured his cheekbone and the campaign nosedived.

The increasingly erratic pass master even helped motivate their other main opponents. Blurting, “F**k off Norway” at a TV crew – even in jest – came back to haunt him several times, not least when they nabbed England’s spot at USA 94.

The Gazza fascination clearly travels – and prevails. Norwegian film director Tom Storvik told FFT: "It both made him popular and unpopular. Some people loved him for all his antics, while some felt it was unnecessary. His sense of humour transcends borders.”

Storvik is particularly interested in that 1990-96 timeline. “He’s one of the most famous footballers in history,” he enthuses. “However, very few people know of his life off the pitch, when you look away from what the tabloids tried to pass as ‘fact’.”

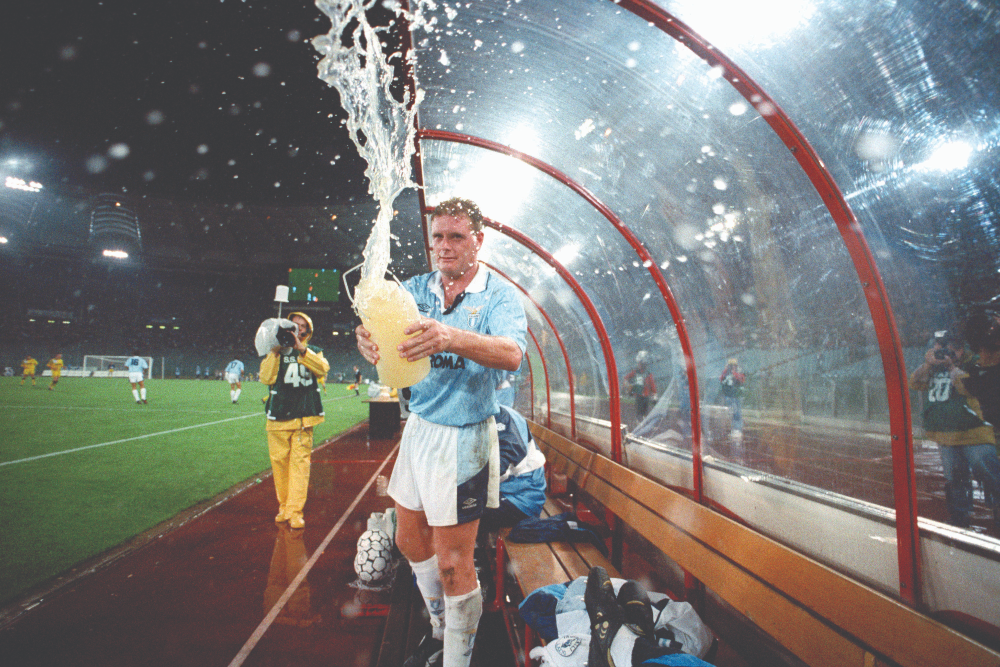

The rabid red-tops were now drastically affecting Gascoigne’s life, but thankfully his on-field career picked up. Moving from Rome to Rangers worked: he won Scotland’s player of the year prize in 1995-96, and made a successful international comeback after playing only twice for England from early February 1993 to March 1995.

Indeed, Gazza later wrote that new gaffer Terry Venables “said he was thinking he might make me England captain” – but the player demurred after foreseeing further press intrusion.

Gazza comes home: Euro 96

England’s pre-tournament trip to Hong Kong certainly caused interest. Gascoigne scuffled on the flight over, which wasn’t reported, and angrily broke stuff when someone happy-slapped him on the journey home. The squad took collective responsibility there, but the papers actively blamed him for the ripped-shirt ‘dentist’s chair’ night out celebrating his birthday, as if he’d led the entire team astray.

“Things like that stick in the players’ throats,” says Pallister, who was in that squad before injury struck. “It’s something you can really do without before a big tournament. At Manchester United, there would always be a negative story before a cup final. You’d come to expect it.”

The hacks did appear to have a point, however, as Euro 96 got going: Gascoigne was dragged off as England fizzled against Switzerland, then looked lost against for much of the game against Scotland.

But then came that goal; divine inspiration to cement a legend. The celebration is iconic, but wasn’t totally popular at the time. Having inadvertently helped to diversify football’s audience, Gascoigne now seemed to endorse that regressive, mid-90s lad culture. But it made a point.

Mark Perryman claims that goal was hugely significant: it may have even saved the United Kingdom. With John Major still in power, talk of Scottish devolution abounded; Gazza was even asked to fly the flag for European unification and plant a tree in Rome by the UK government. “Don’t ask me what that was about,” a befuddled Gascoigne later said, although he exchanged letters with Major anyway (cheekily addressing him as ‘John’ in his response).

“I’ve had this conversation a lot,” explains Perryman. “What if Scotland had won? It’s obvious: they would have voted for independence.”

Then-Rangers club-mate and Scotland foe Stuart McCall was surprised at Gascoigne’s behaviour upon his return to Ibrox for pre-season.

“I think if Scotland had beaten England, a few of us would have given it to Gazza for about six months,” he tells FFT. “But I must say, when he came back he was very humble and didn’t rub our noses in it at all. That was a shock because we thought he’d slaughter us. He was good as gold.”

The nation got seriously giddy when England handed the Netherlands some long overdue payback in their final group match, with Gascoigne gliding through their defence like a bleached swan.

Yet his tournament would end with an enduring question, after his late tap-in miss against Germany. Would he have reached that ball without the booze? It rather negated the impressive extra-time run that got him anywhere near it.

“He actually had amazing natural fitness,” says Henry Winter. “Partly it was willpower, to get the ball and then impress everyone. But it was nervous energy as well.”

That night, Gascoigne returned to the team hotel, 'ran to my room and had a good cry' – after pouring a tub of ketchup all over Robbie Fowler.

Hoddle bears the brunt: France 98

You might imagine that Gascoigne and new England boss Glenn Hoddle would be kindred spirits football-wise, but alas: Hoddle was a born-again Christian and faith-healer enthusiast, while Gazza was getting IRA death threats after playing a faux-flute during an Old Firm derby.

They were never going to be fake-bosom buddies. Journalist Alyson Rudd has an added theory. “Most managers are tougher on players who play a bit like them,” she says. “You don’t want someone who reminds you of what you were when you were younger.”

Hoddle was actually criticised for picking him early on, after disturbing images of Paul’s battered wife Sheryl emerged. A grimmer Gazzamania was apparent. His book turns positively Macbeth-like here: guilt, paranoia, obsession. Yet he was there when England came calling, playing with superb discipline in their 1997 qualifier against Italy at Rome’s Stadio Olimpico. The lure of the World Cup, safely secluded with the lads, was everything.

ut then a calamitous cocktail of high-profile pub crawls and poor form in warm-up games exhausted Hoddle’s patience. Perhaps just phoning Gazza at home would have been wiser, though.

“I was in La Manga when he lost it,” says Winter, who views Gascoigne and ‘Gazza’ as almost rival alter-egos. The former could be impressively thoughtful about the game, but 'there was the dark side, too'.

Did he really trash Hoddle’s room? “I think the press got a bit carried away,” suggests Winter. “And to be honest, if someone had just broken my heart with Kenny G playing in the background, I may have taken out more than a standard lamp. I think many of us disagreed with Glenn at the time, but looking back it was the right decision. He had Paul Scholes coming through, and a new way of playing.”

Gascoigne had been overtaken by a modern football culture that he’d arguably helped create. But while we tend to remember a rapid decline, 1998/99 was actually a good season for him at new club Middlesbrough. They finished 9th and England rumours resurfaced.

“That creativity and genius would still come out,” says Pallister, then back with Boro as well. “If he’d never done that cruciate with Spurs, I think we’d be calling him the best English player ever.”

Sympathy wasn’t always forthcoming, though: in 2000, Middlesbrough tried to boost his fitness with a summer loan move… to Norway. Several coaches responded less than politely. “Ha ha ha,” scoffed Viking’s Benny Lennartsson. “That’s my answer.”

Even then, World Cup hopes flickered. In January 2002 the midfielder, now at Everton, terrorised Leyton Orient in the FA Cup, and the BBC ran a poll: “Does Gazza deserve an England recall?” Forty-two per cent of the replies said yes.

An old Spurs colleague chased shadows that afternoon. “He was incredible, five yards ahead of everyone,” recalls Minton. “We’ll never see someone like that again. Even in that match, he was trying to help me on the pitch – ‘Don’t stand still, keep on your toes, keep moving’. He was the world’s best player once, and so generous. It’s such a shame.”

Finding Gazza fans isn’t hard, but the question will forever beg of what he could have been – the legend transcends the player, after all. Might he have enjoyed a different career if he’d joined Alex Ferguson in 1988?

“At Spurs he was allowed to play in a role that suited him,” says Rudd. “Slightly more relaxed in the disciplinary sense, and a bit more jolly. In Manchester, I don’t think it would have worked.”

In fact, knowing Fergie, he might well have pulled Gazza out of those Italia 90 warm-up games and none of this would ever have happened. No World Cup run. No diverse new football audience. No Premier League. No Champions League. No FourFourTwo, even.

Or maybe we’d now be reminiscing about Neil Webbamania instead.

This feature first appeared in the from February 2020 issue of FourFourTwo. Buy the latest issue now.