In our guides to the classics, experts explain key literary works.

Ask someone when they first read Jane Eyre, and they will no doubt remember: the voice of its protagonist leaps off the page as if to grab you by the forearm, pulsating with life.

Passionate, determined, and fiercely protective of her claim to happiness, Jane possesses a strength of character that utterly belies the plainness and penury of her beginnings.

Even those who haven’t read this novel, first published in 1847, are likely to associate it with popular representations of governesses and madwomen, which Jane Eyre helped enshrine as icons of the Victorian era.

Narrated from the first-person point of view, Charlotte Brontë’s masterpiece is a landmark in the novel of interiority, the history of feminism, and the representation of religion and race.

Brontë’s early life

Jane Eyre is subtitled, “An Autobiography,” and the events of the novel – at once domestic and strange, familiar and fantastical – are deeply shaped by the experiences of its author. Born in Yorkshire to a prickly curate father, Charlotte Brontë was surrounded by death as a child. She lost her mother at the age of five, followed by two older sisters when a typhoid outbreak swept through their boarding school.

From then on, Charlotte remained at home with her other siblings – Anne and Emily, and her ne’er-do-well brother Branwell. Together, they lost themselves in the creation of a fictional world called “Glass Town,” which they catalogued meticulously in tiny paper booklets.

After failing disastrously as a schoolteacher and governess (which Charlotte relates in trenchant letters to family and friends), she and her sisters sought to make a career out of their childhood passion.

In the space of two years, they would publish Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, three undeniable classics in what one critic has dubbed a second “Northumbrian Renaissance.”

A child’s eye

The early chapters of Charlotte’s novel take us deep into the mind of Jane Eyre, an orphan who has been reluctantly accepted into the household of a wealthy aunt. Though only ten years old, Jane is treated worse than a servant, abused by her cousins and constantly reminded her existence is an unwanted burden.

The family nicknames her “Madame Mope,” but Jane is anything but sullen. On the contrary, she harbours within her the spirit of a “rebel slave,” desperately seeking love but unwilling to abase herself in pursuit of her aunt’s (or indeed anyone’s) approval.

When Jane is wrongfully accused of attacking her vicious cousin, she is locked in the “red-room,” the bedchamber of her dead uncle. She burns with fear and resentment, and the room becomes a potent allegory for the psychological misery inflicted upon children.

Hope seems to arrive in the prospect of a charity school for orphans, but Jane’s restless spirit stands poised to chafe against its gospel of Christian meekness. In her interview for admission, the director recounts for Jane’s edification the example of

a little boy, younger than you, who knows six Psalms by heart: and when you ask him which he would rather have, a gingerbread-nut to eat, or a verse of a Psalm to learn he says: ‘Oh! The verse of a Psalm!’[… and] gets two nuts in recompense for his infant piety.

Unimpressed by the child’s craven obeisance, Jane remarks simply, “Psalms are not interesting.”

The scenes at Lowood School, an institution for the poor, are drawn from Charlotte’s own knowledge of the boarding school that killed her sisters. The children are half-starved and beaten while their zealous benefactor espouses the virtues of poverty. Jane’s only solace is a kindly teacher and the ethereal student Helen Burns, who possesses Christ-like powers of submission.

The death of Helen from typhus points to the impossibility of moral perfection in a bleak and fallen world. While Jane admires her friend, she quickly sees that her own path will involve a different kind of suffering and resistance.

An unconventional courtship

Jane is often described as “plucky” or “spunky,” a quality best revealed by her energetic self-reliance. A self-made woman, she spends the next eight years at Lowood educating herself so she can seek out better opportunities elsewhere.

After advertising in the local newspaper, she gets hired to be governess at Thornfield Hall, a large estate with a mysterious proprietor. At this point in the novel, the tone shifts from social criticism to gothic romance, as Jane falls deeply in love with the owner of the estate, Edward Rochester.

The unconventional courtship between the star-crossed (and class-crossed) lovers is one of the novel’s chief delights. Rochester is world-weary and emotional, a dissipated aristocrat who becomes captivated by Jane’s frankness and inner strength. Jane sees glimmers of a finer nature beneath Rochester’s brutish façade, but resists the temptation to become his plaything or ornament.

In a daring renovation of the courtship plot, Brontë depicts Rochester as the needier and more flirtatious of the two. To secure Jane’s interest, he is not above pretending to be engaged to another woman or dressing as a female gypsy to ascertain the true nature of her feelings.

Jane, however, refuses to sacrifice her personal dignity at the altar of romantic love. When Rochester asks her to remain his ward’s governess after he marries his supposed fiancée, Jane bursts forth:

Do you think I am an automaton? – a machine without feelings? and can bear to have my morsel of bread snatched from my lips, and my drop of living water dashed from my cup? Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong! – I have as much soul as you, – and full as much heart!

In a move that scandalised some of Brontë’s critics, Rochester responds warmly to Jane’s principled self-defense and immediately proposes marriage, explaining, “My bride is here […] because my equal is here.”

Madwomen and missionaries

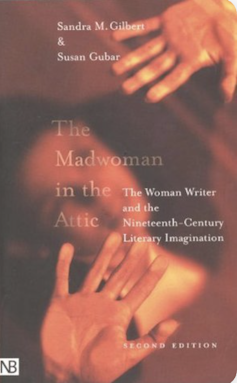

Most people are familiar with the phrase “the madwoman in the attic,” but few know it comes not from the novel but from a pioneering work of feminist criticism inspired by Brontë’s example.

In The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination (1979), Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar placed the incredible plot twist at the heart of Jane Eyre – that Rochester is secretly married to a mixed-race madwoman from the West Indies, who is confined to the third floor of his house – at the heart of a new symbology of writing by women.

“By projecting their rebellious impulses not into their heroines but into mad or monstrous women (who are suitably punished in the course of the novel or poem),” they write, “female authors dramatize their own self-division, their desire both to accept the strictures of patriarchal society and to reject them.”

Bertha Mason, the madwoman, thus becomes a monstrous double of Jane – a transgressive woman of violent temper who demonstrates what happens when women are oppressed by unequal marriages or violate social norms.

The invention of Bertha is a brilliantly lurid device to keep Rochester and Jane apart. But it has not always sat well with readers.

In Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), the Dominican writer Jean Rhys retells the story from Bertha’s perspective, humanising the bestial other. In place of the “clothed hyena” that Jane observes, Rhys shows how Bertha’s subjection to colonial schemes of exploitation and domination is as much responsible for her madness as any racial or genetic traits. Instead of Jane, it is Bertha who complains of injustice.

Brontë further develops the colonial contexts of Jane Eyre in the novel’s final section, when, after the collapse of her engagement to Rochester, Jane takes up residence with an earnest missionary and his sisters. Here, Jane finally finds herself in a community of equals, except it lacks the romantic dimension of her relationship with Rochester.

When the missionary, St. John Rivers, proposes marriage to Jane, it is because he judges her to be the perfect help-meet for his religious labours in India, not because he desires her erotically. Where Rochester was excessively sensual (we are made aware that he married Bertha for sex as well as money), St. John is coldly ambitious — not a bad man, per se, but one who sees his spiritual destiny as incompatible with the life of the heart.

Through the colonial activities of both men, Brontë associates the wider British empire with masculine egoism and derogation from equality between the sexes. Such a place, she suggests, is likely to produce “revolted slaves” not unlike her heroine Jane.

A radical solution

The most famous line of Jane Eyre – “Reader, I married him” – encapsulates how this sometimes dispiriting novel moves inexorably toward maturity and fulfilment.

While still considering St. John’s proposal, Jane hears Rochester’s voice beckoning to her through the ether – a moment of occult indulgence that recalls the more mythopoetic style of Charlotte’s sister, Emily. Fortunately, the voice inspires Jane to return to Thornfield, where she finds that Bertha has burned the house to the ground, killing herself in the process, and leaving Rochester blinded and maimed.

A sombre mood prevails as the two lovers reacquaint themselves, but Jane resumes her teasing manner when she realises that Rochester has become insecure toward her because of his disabilities, not because his passion has cooled.

In contrast to her scepticism about St. John’s mission, Jane delights in the possibility of serving as Rochester’s caretaker and nurse because she is motivated by love rather than duty.

In a culture where most people, but women especially, were encouraged to sublimate their desires to the goals of more powerful men, Jane Eyre offers a radical solution. By marrying a man who has become her physical and financial dependent – but who remains an equal romantic partner – Jane can enjoy both power and femininity, which for many Victorians was an improbable combination.

As Jane puts it,

I hold myself supremely blest – blest beyond what language can express; because I am my husband’s life as fully as he is mine.

Her confident assertion of dignity, of integrity, and of moral and social equality is as relevant to our own time as it was to hers.

Matthew Sussman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.