For millennia, humans had one obvious and reliable source of light – the Sun – and we knew the Sun was essential for our survival.

This might be why ancient religions – such as those in Egypt, Greece, the Middle East, India, Asia, and Central and South America – involved Sun worship.

Early religions were also often tied up with healing. Sick people would turn to the shaman, priest or priestess for help.

While ancient peoples used the Sun to heal, this might not be how you think.

Since then, we’ve used light to heal in a number of ways. Some you might recognise today, others sound more like magic.

From warming ointments to sunbaking

There’s not much evidence around today that ancient peoples believed sunlight itself could cure illness. Instead, there’s more evidence they used the warmth of the Sun to heal.

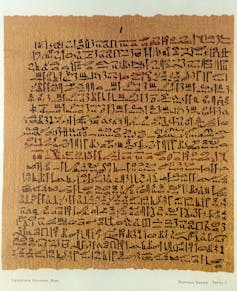

The Ebers Papyrus is an ancient Egyptian medical scroll from around 1500 BCE. It contains a recipe for an ointment to “make the sinews […] flexible”. The ointment was made of wine, onion, soot, fruit and the tree extracts frankincense and myrrh. Once it was applied, the person was “put in sunlight”.

Other recipes, to treat coughs for example, involved putting ingredients in a vessel and letting it stand in sunlight. This is presumably to warm it up and help it infuse more strongly. The same technique is in the medical writings attributed to Greek physician Hippocrates who lived around 450-380 BCE.

The physician Aretaeus, who was active around 150 CE in what is now modern Turkey, wrote that sunlight could cure chronic cases of what he called “lethargy” but we’d recognise today as depression:

Lethargics are to be laid in the light, and exposed to the rays of the Sun (for the disease is gloom); and in a rather warm place, for the cause is a congelation of the innate heat.

Classical Islamic scholar Ibn Sina (980-1037 CE) described the health effects of sunbathing (at a time when we didn’t know about the link to skin cancer). In Book I of The Canon of Medicine he said the hot Sun helped everything from flatulence and asthma to hysteria. He also said the Sun “invigorates the brain” and is beneficial for “clearing the uterus”.

It was sometimes hard to tell science from magic

All the ways of curing described so far depend more on the Sun’s heat rather than its light. But what about curing with light itself?

English scientist Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) knew you could “split” sunlight into a rainbow spectrum of colours.

This and many other discoveries radically changed ideas about healing in the next 200 years.

But as new ideas flourished, it was sometimes hard to tell science from magic.

For example, German mystic and visionary Jakob Lorber (1800-1864) believed sunlight was the best cure for pretty much anything. His 1851 book The Healing Power of Sunlight was still in print in 1997.

Public health reformer Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) also believed in the power of sunlight. In her famous book Notes on Nursing, she said of her patients:

second only to their need of fresh air is their need for light […] not only light but direct sunlight.

Nightingale also believed sunlight was the natural enemy of bacteria and viruses. She seems at least partially right. Sunlight can kill some, but not all, bacteria and viruses.

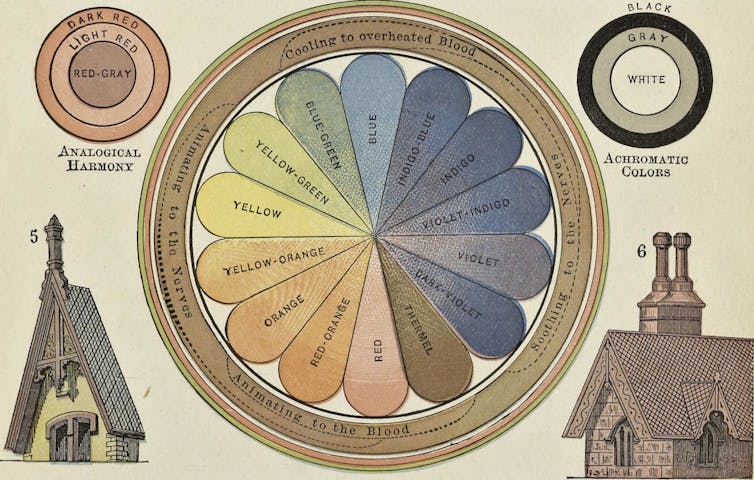

Chromotherapy – a way of healing based on colours and light – emerged in this period. While some of its supporters claim using coloured light for healing dates back to ancient Egypt, it’s hard to find evidence of this now.

Modern chromotherapy owes a lot to the fertile mind of physician Edwin Babbitt (1828-1905) from the United States. Babbitt’s 1878 book The Principles of Light and Color was based on experiments with coloured light and his own visions and clairvoyant insights. It’s still in print.

Babbitt invented a portable stained-glass window called the Chromolume, designed to restore the balance of the body’s natural coloured energy. Sitting for set periods under the coloured lights from the window was said to restore your health.

Indian entrepreneur Dinshah Ghadiali (1873-1966) read about this, moved to the US and invented his own instrument, the Spectro-Chrome, in 1920.

The theory behind the Spectro-Chrome was that the human body was made up of four elements – oxygen (blue), hydrogen (red), nitrogen (green) and carbon (yellow). When these colours were out of balance, it caused sickness.

Some hour-long sessions with the Spectro-Chrome would restore balance and health. By using its green light, for example, you could reportedly aid your pituitary gland, while yellow light helped your digestion.

By 1946 Ghadiali had made around a million dollars from sales of this device in the US.

And today?

While some of these treatments sound bizarre, we now know certain coloured lights treat some illnesses and disorders.

Phototherapy with blue light is used to treat newborn babies with jaundice in hospital. People with seasonal affective disorder (sometimes known as winter depression) can be treated with regular exposure to white or blue light. And ultraviolet light is used to treat skin conditions, such as psoriasis.

Today, light therapy has even found its way into the beauty industry. LED face masks, with celebrity endorsements, promise to fight acne and reduce signs of ageing.

But like all forms of light, exposure to it has both risks and benefits. In the case of these LED face masks, they could disrupt your sleep.

This is the final article in our ‘Light and health’ series, where we look at how light affects our physical and mental health in sometimes surprising ways. Read other articles in the series.

Philippa Martyr does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.