The 2024 Paris Olympics will be the first to achieve total gender parity. From 26 July to 11 August, 5,250 male and 5,250 female athletes will compete in the 33rd edition of the modern Games.

By meeting this figure, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) has fulfilled the 11th recommendation of the Olympic Agenda 2020, which aimed for 50:50 gender balance between male and female athletes, and an increase in the number of mixed team events, which will number around 20 of the 329 total events at the games.

Women’s participation in the Olympics unofficially began at the second edition of the modern Games, also held in Paris in 1900. Of the 997 athletes, 22 were women, who competed in five disciplines: tennis, sailing, croquet, horse riding and golf.

It is often believed that women did little sport in the past, though this had little to do with a lack of interest in physical activity, and a lot to do with gender politics that imposed rigid segregation between young men and young women. Sport played a central role in keeping the sexes apart.

‘Muscular Christianity’: the ideology underpinning the modern Olympics

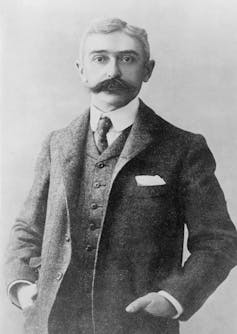

The educational ambitions of Pierre de Coubertain, the father of the Modern Olympics, were strongly influenced by what was known as “muscular Christianity”, a movement that saw sport as central to the formation of faith and masculinity in young men.

In 1883, at age 20, Coubertain attended the physical education programme at Rugby, the British private school that gave its name to the ball sport and is the setting for Thomas Hughes’ novel Tom Brown’s School Days.

Scarred by France’s humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, Coubertin saw the English sporting mindset as a solution to the French’s poor preparation for war. In time, he also extolled the diplomatic potential of sport to maintain peace between empires. This association of sport with national struggles, imperialism and war swept aside more playful and pluralistic visions of sport, leading Coubertin to conceive the Olympics as an exclusively masculine celebration of presumed white superiority.

The modern Olympics did not accommodate women graciously. In fact, the Olympics were essential in the process of keeping modern sport a male domain, and it was only through perseverance and struggle that women’s presence in the Games became more accepted and officialised.

One key figure in this fight was Alice Milliat, who founded the International Women’s Sports Federation in 1921 after the IOC rejected calls to include women in more events. That same year she organised the first Women’s Olympiad, which was repeated in the following two years, in addition to the separate Women’s World Games, which were held four times between 1922 and 1934.

The Second Women’s Olympiad, held in Paris in 1922, attracted 20,000 spectators. In 1960 one of its members revealed that, in 1923, the IOC debated how to deal with the effects of feminism on sport, and reluctantly agreed to expand women’s events in order to take control of their growing presence and participation in these events.

A lack of gender parity on the IOC board

While it is a historically feminist demand, gender parity may hide the ulterior motive of remaining in control.

The 1996 Olympic Charter stated the IOC’s commitment to promoting the presence of women “at all levels and in all structures, particularly in the executive bodies of national and international sports organizations with a view to the strict application of the principle of equality of men and women”.

However, parity on the executive board was not included in the Olympic Agenda 2020. If it had been, the 11th recommendation would remain unfulfilled, since the IOC board is currently composed of 11 men and 5 women.

Undermining female athletes

Beyond the numbers, sport is governed by principles that make effective equality impossible, one of which is the dogma of sexual segregation that underpins the very idea of parity.

Supposedly upheld to protect the female category, the separation of the sexes has shaped the decisions of sporting federations every time a female athlete has called male superiority into question.

This happened to Chinese shooter Zhang Shan after she won the gold and broke the Olympic record in mixed clay pigeon shooting at the Barcelona 1992 Games. After her victory, the International Shooting Union banned women from participating, so Zhang was unable to defend her gold in the Atlanta 1996 Games, even though they were touted as promoting female participation.

In Paris 2024 there will be a mixed shooting event, but with teams consisting of one man and one woman. This form of “mixed” model will avoid direct competition between men and women.

Ski jumper Lindsay Van was also unable to defend her record at the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics, as women were banned from participating in the event, despite the fact that it was a woman who held the overall record. The International Ski Federation cited possible future reproductive problems in female jumpers to justify the ban. The same arguments were used to bar women from sport in the early 20th century, over a century before.

Anecdotal though they may seem, these episodes show that any move towards equality among genders always ends up imposing competitive constraints on women. For years these took the form of sex verification tests, and today testosterone levels are scrutinised, keeping many African women out of competition.

In a more cultural vein, France has barred athletes wearing head coverings from competing in its Olympic team, while female athletes in several disciplines have pushed back against clothing that sexualises them.

Female athletes’ bodies remain one of the main objects of regulation by sports committees. As long as sport is segregated by sex, the difference between men and women will always have to be marked, preserved and policed.

Olatz González Abrisketa no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.