A visual narrative of Somnath Hore’s searing observations — ranging from the Bengal Famine (1943), the peasant unrest (mid-1940s) to Partition and migration from East Bengal — the exhibition Birth of a White Rose reflects India’s socio-political dynamics at the time. Named after his iconic work, which won him the Lalit Kala Akademi National Award in 1962, the ongoing exhibition at New Delhi’s Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA) celebrates his centenary. “It captures some of his most incredible works, including his early works in the 1950s and 60s. His artistic horizon remained socialist and humanist,” says Roobina Karode, director and chief curator of the museum.

Partition on rice paper

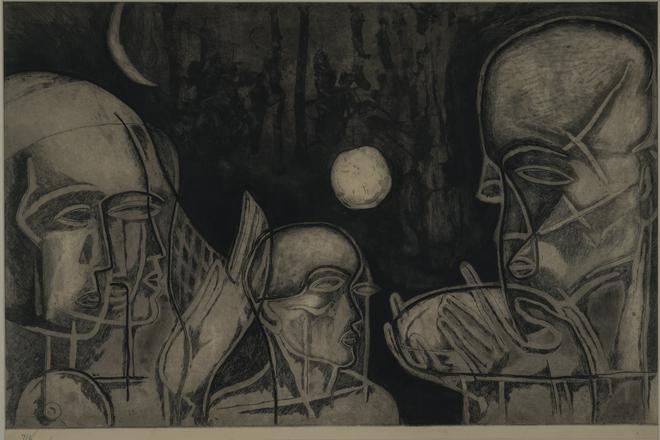

Somnath chronicled class conflicts and violence in diverse mediums, which expressed his personal philosophy and collective ideology of existential amelioration, equality and empathy. While partaking in rescue operations as a communist activist in the early-1940s, he captured people’s struggle for survival and dignity in fast-paced documentative sketches. Some of these drawings were published in the Communist Party magazine Janajuddha (People’s War), along with his diary entries and sketches of the Tebhaga movement. The one with red flags dotting a mass gathering, an oil painting titled CP Rally (1955), is one of his earliest works on display. Many of these drawings were transferred to woodcut prints in the 1950s.

Somnath’s etchings and engravings from the 1960s, such as Refugee Family, resonate with the collective pathos of Partition. He approaches the theme of Mother and child with a different gaze time and again, sometimes through the gleam of bronze and at others through strong, rapid lines drawn on paper. His response to the Vietnam War and socio-political unrest in Bengal by the late-1960s and 1970s is voiced in the Wounds series, a powerful play of textures on a paper that’s occasionally tinted red. In many of his artworks, Somnath also uses rice paper.

Woodcuts and etchings

The exhibition showcases nearly 180 of Somnath’s works, including 21 metal plates (19 in zinc and two in copper), which he used for making prints, lithographs, woodcuts and etchings. Roobina says, “As with all exhibitions, artworks come from all over. Some are our own artworks and belong to the KNMA collection. Some artworks are borrowed from significant collectors like Neerja and Mukund Lath, Rohit Singh Mahiyaria, Darashaw Collection, The Alkazi Collection of Art and other institutions in India and worldwide.”

Touted as a sub-continental match to Austrian artist Oskar Kokoschka or German printmaker Käthe Kollwitz in artistic spirit and aesthetic idioms, Somnath mirrored radical changes in the artistic language seen in the works of Zainul Abedin, Chittaprosad and many other artists originating from the Calcutta Group. Distancing themselves from the European academicism and the lyricism of Bengal and Santiniketan schools, these artists manifested the power of figurative representation and social realism. Somnath, a student of Abedin and friend of Chittaprosad, shaped his own visual lexicon, with time attaining a stylistic singularity.

On display till September 30 at Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in Saket, New Delhi.