HARRISBURG, Pa. — About 40% of the hundreds of thousands of railroad freight cars that roll through Pennsylvania annually carry hazardous materials, a rail industry official told lawmakers Monday, but the U.S. Constitution prevents the state from setting comprehensive rules for how they operate.

The testimony at a state Senate Transportation Committee hearing on the catastrophic Feb. 3 derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, came on the same day another committee scheduled a possible vote on issuing a subpoena to the CEO of Norfolk Southern, operator of the derailed train.

An empty chair was placed at the front of a hearing last week held by the Senate Veterans Affairs & Emergency Preparedness Committee after the company cited an ongoing federal investigation as its reason for declining to attend. On Monday, Josh Herman, a spokesperson for committee Chairman Sen. Doug Mastriano, R-Franklin, said the committee would conduct a vote Wednesday on whether to subpoena company CEO Alan Shaw.

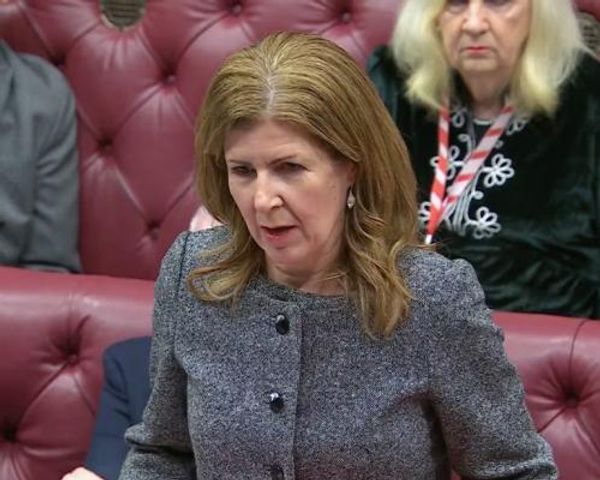

Committee member Sen. Maria Collett, D-Montgomery, said in an interview she would vote for a subpoena.

But she said she wasn’t going to “hang her hat” on getting answers. Instead, Collett said she would focus on making sure the state used appropriate comparisons in its environmental testing.

The Department of Environmental Protection maintained on Monday there are “no known concerns” for air or water quality in Pennsylvania as a result of the derailment. But Collett said people should know that state thresholds for what are considered unsafe chemical levels often are not based in medicine or science.

“Those numbers can be arbitrary,” said Collett, who is also a trained nurse and was in Monaca for last week’s Senate Veterans Affairs & Emergency Preparedness Committee hearing. “As we learn more, we may shift our thinking on what is an acceptable level.”

Norfolk Southern did not immediately respond to an email sent to its media relations office.

Residents from both sides of the Pennsylvania-Ohio border at the first hearing told lawmakers of being traumatized by explosions, billowing smoke clouds and fears for their health.

At the start of Monday’s hearing, Sen. Wayne Langerholc, R-Cambria, who chairs the transportation panel, said Pennsylvania has 65 railroad companies operating within its borders — the highest figure in the nation — and its roughly 5,000 miles of track make for the fifth-largest total.

The hearing focused on the transportation of hazardous materials on those tracks, and much of the testimony came from Carl Belke, president of Keystone State Rail Association, a rail industry trade group. He said hundreds of thousands of cars hauling freight travel through the state during a single year, and he estimated 40% contain hazardous materials. There have been four derailments with hazardous materials in the past decade — a tiny fraction of overall traffic, Belke said.

Belke could not provide overall numbers for derailments because the federal government has a reporting threshold for such incidents of $25,000 in damage, he said. Many derailments involve far less damage. Belke said those incidents might involve low speed and a single wheel, and witnesses likely can’t even tell the train has derailed.

“That kind of stuff happens once a week, twice a week in Pennsylvania,” he said.

Since the catastrophe in East Palestine, Pennsylvania officials have stressed the outsized role the federal government plays in regulating rail commerce.

Rodney Bender, a railroad safety manager for the state’s Public Utility Commission, said Monday that the agency has 10 inspectors whose job is to look for railroad violations and report them to the federal government.

Questioned by state Sen. Marty Flynn of Lackawanna County, the top Democrat on the committee, Bender said PUC has no power to fine offenders to compel better behavior.

“So if there is no fine, why would they do it?” Flynn asked.

Gladys Brown Dutrieuille, chairperson of the PUC, said federal authorities might impose a fine.

Mike Carroll, acting secretary of PennDOT, said Pennsylvania’s ability to have its own regulations on railroads is prohibited by the U.S. Constitution.

Questioned by Flynn, Belke testified there is no government requirement for a certain number of employees on a freight train. He said his career had spanned nearly 50 years. At the start of that span, he said, there were five or six employees on trains and while the number has declined, so has the number of injuries.

The caboose that used to be attached at the tail end of a train and which was essentially a traveling office was “one of the most dangerous places to be,” Belke said. Now, several instruments, like a GPS and an air brake pressure sensor, are located at the end of a train.

After the hearing, Langerholc said lawmakers will continue to look for ways to make regulatory improvements.

Collett drew parallels between the derailment and the finding, years ago, of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, in drinking water near southeastern Pennsylvania military bases where firefighting foam was used.

Studies have associated PFAS exposure with infertility, high cholesterol and a variety of cancers. Collett noted that in addition to any potential dangers created by the burning of vinyl chloride that was released from derailed tanker cars in Ohio, first responders used firefighting foam at the scene.

Nine years after the PFAS crisis emerged in her district in Montgomery and Bucks Counties, Collett said, “We are still searching for answers.”

Also on Monday, the administration of Gov. Josh Shapiro announced the opening of a Health Resource Center at the Darlington Township Building in Beaver County for people concerned about health effects from the derailment.

---------