The news that Topshop is coming back has sent millennials everywhere into a nostalgic frenzy. This week, my feed has been awash with archive looks from bygone Kate Moss for Topshop collections. Suddenly, my algorithm is spewing out indie sleaze-tinged outfits, boho dresses and an alarming amount of fringing. Like any self-respecting thirty-something millennial, I am revelling in this sudden flurry of early aughts nostalgia, but let’s be realistic, it would take more than Kate Moss and an as-yet-unconfirmed bricks and mortar Topshop store to save Britain’s High Street.

“I was heartbroken—as somebody who spent many a Saturday there—when Topshop left,” says Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London for the last eight years. We’re meeting on John Lewis’ rooftop to talk about his plans to regenerate the country’s most famous high street, and it turns out we have something in common.

Growing up in sleepy North Devon, London’s Oxford Street epitomised everything I felt deprived of—fashion, excitement, hustle and bustle. When I moved to London in 2010, Topshop was in its heyday, and Oxford Street felt like the epicentre of opportunity. This belief was confirmed when I got my first internship a year later at a PR studio on Margaret Street just behind Oxford Street where I was instructed to scuttle every day to get the owner a shot of wheatgrass and a single slice of apple from a long-since shuttered juice bar. However, 14 years later, I rarely find myself in this part of town anymore.

“If we're honest, over the last 10-20 years, this street looks tired,” Khan tells me. He plans to reform Oxford Street to its former glory (though he’s quick to point out his plans are about looking to the future rather than in the rearview) and make the 1.2-mile stretch to London what Times Square is to New York, La Ramblas is to Barcelona, and Les Champs-Elysées is to Paris. On my way to meet him, a gaggle of American tourists asked me which stop was “Oxford Circle”, which I took as proof that we’ve not quite reached world recognition.

However, being here on Oxford Street, I’m reminded that it once was the centre of the world—my world, anyway. I moved to London in the autumn of 2010 to study Fashion Journalism, three years after Kate Moss debuted her collection for Phillip Green’s high street giant, which my friends and I lovingly referred to as ‘Toppers’. I might’ve missed Mossy’s launch, but now that I was at last living in London, I vowed I’d never miss out again.

As a born and bred Londoner, Khan also has happy memories of Oxford Street in its heyday. As a teenager, he worked at Debenhams, Barretts and John Lewis and remembers the street as vibrant, thriving, and successful so he recognises the contrast today. “There are many stores that have left Oxford Street...I want really good retailers coming to Oxford Street.” Khan says pedestrianising is the way to lure people back. “All the evidence suggests a pedestrianised street, a well-designed street is safer, is greener, is healthier.”

Khan believes banning traffic will not only entice customers back, it’ll attract better retailers and leave fewer vacant stores - a “win win win”, as he puts it. As the father of two daughters, he’s felt the absence of the street's most-famous store—Topshop. For Londoners like myself, Topshop’s closure felt like the death knell for Oxford Street. Despite surviving the collapse of the high street which claimed scores of stores nationwide—including the tiny Topshop I shopped in as a teenager—Oxford Street has since been ravished by the rise of online retail, the pandemic, and years of austerity.

“Topshop was an extremely fun era for me,” remembers Anna Lowe, 35, who worked in the concessions part of the store from 2011-2012. She remembers that as a concession staff, she was looked down on by the “proper” Topshop staff which created a kind of Sixth Form environment. “The canteen area was super fun though, everyone was in their early twenties, and just there for fun,” adds Lowe.

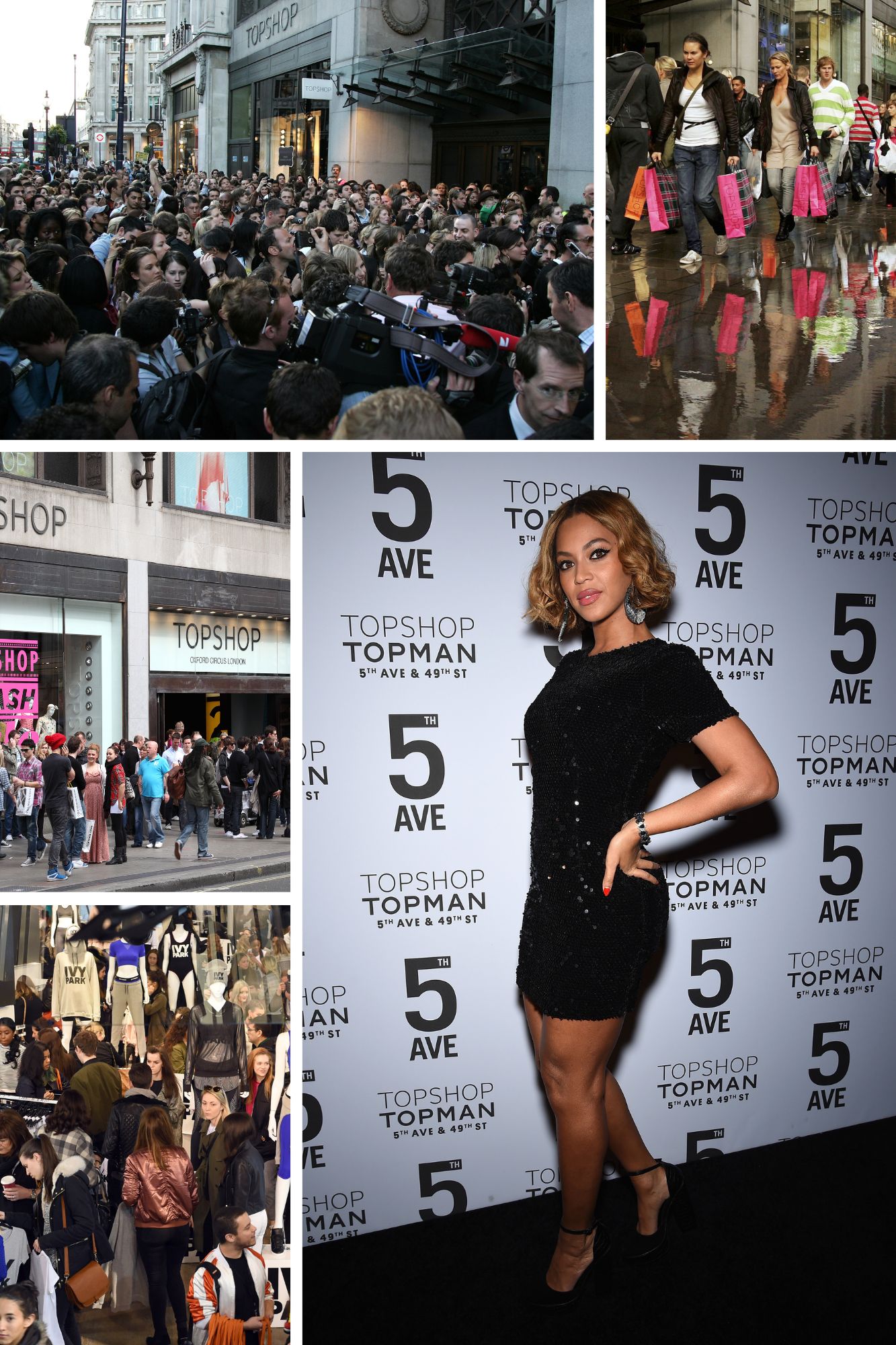

Another Topshop staffer remembers it as a “weird place to work ‘cos one minute, you’d have Phil Green walking around, and other times you’d be like, ‘Oh, Beyonce came in yesterday.’” In today’s saturated retail market, it’s hard to imagine any one store having that much cache.

Born Londoner, Dee Corsi, Chief Executive of New West End Company, which is working with the Mayoral Development Corporation (MDC) to revitalise Oxford Street, remembers the area as foundational growing up in the city. As the mother of a teenager, she understands that if shoppers like her daughter want something, they’ll just buy it online, so brick-and-mortar stores need to offer more than customers can already get online. “Immersive experiences” are what Corsi says stores need today.

Whether it was the mall culture of the 90s and noughties via films like Clueless and Mean Girls or the hype of limited-edition collections like Kate Moss for Topshop or H&M’s designer collaborations—which in its heyday saw shoppers camping overnight to get pieces from Karl Lagerfeld, Stella McCartney, Versace and Marni—shopping has always been about the experience.

“As a child, my frazzled parents would spend Christmas Eve heaving my siblings and me onto the Victoria line to traipse around Hamleys and the Disney Store to make last-minute additions to our Santa lists,” remembers Jadie TroyPryde, 33, who grew up in East London. Later as a pre-teen on the hunt for silky cargo pants, CDs and corduroy baker boy caps, she’d drag her eldest brother around to be her shopping chaperone at Jane Norman and HMV.

Nowadays, TroyPryde says she rarely finds herself in central London, “and rarer still that I’ll do any shopping in real life.” But she hopes that her nieces and nephew “get to experience the magic of a sparkly Oxford Street pilgrimage.”

Saving money to spend on Oxford Street did feel like a rite of passage and one that has seemingly been passed down. After I met the mayor, I ambled through Oxford Circus and saw hordes of teenage girls marching towards Bershka and Stradivarius, ironically, probably looking for silky cargo pants and bootcut jeans.

Fashion might be enjoying a love affair with all things nineties and noughties, but it’s hard to imagine Oxford Street ever again pulling in customers as it did when I first moved to London in 2010. On the other hand, I worry about the safety of girls if the area is to become pedestrianised. As a woman, I feel safer in areas with traffic. Buses and taxis are not only crucial for those with disabilities, they provide light—and if needed—an escape. The threat of Oxford Circus becoming a ‘no-go zone’ has been put to Khan before. To this he says; “I don't think crime is inevitable. I think crime is preventable.” The issue of violence against women and girls is a huge source of concern to him, both as a father and as a mayor. He says he’s spoken to the home secretary Yvette Cooper, and he’s “excited at the government's plans and its mission to reduce violence against women and girls over the course of the next few weeks, months and years.”

On a practical level, Khan plans to support the police and make sure there’s good CCTV, well-designed streets, and well-designed shops. For Angela Rayner’s part, not only is she backing Khan’s plans, but she’s pledged to halve violence against women and girls within a decade as part of the new Labour government’s manifesto. They’re ambitious plans, and as a woman and a Londoner, I’m rooting for both of them, but with gender-based violence now a nationwide epidemic and 3352 reported crimes in London’s West End in the most recent month, according to The Met’s Crime Map, it’s hard not to feel fearful for the next generation of girls being enticed by the soon-to-be no so bright lights of Oxford Circus, especially if the ultimate teenage shopping haven does make its long-awaited return.