Geoff Notkin was born in New York City and raised in London, England. He is a meteorite specialist, author, TEDx speaker, Emmy-winning television host, film producer, and namesake of Asteroid 132904, "Notkin," as recognized by the Minor Planet Center.

Part of my personal cosmic journey will come to an end on July 22, 2023, when my private meteorite collection is sold by Heritage Auctions of Dallas.

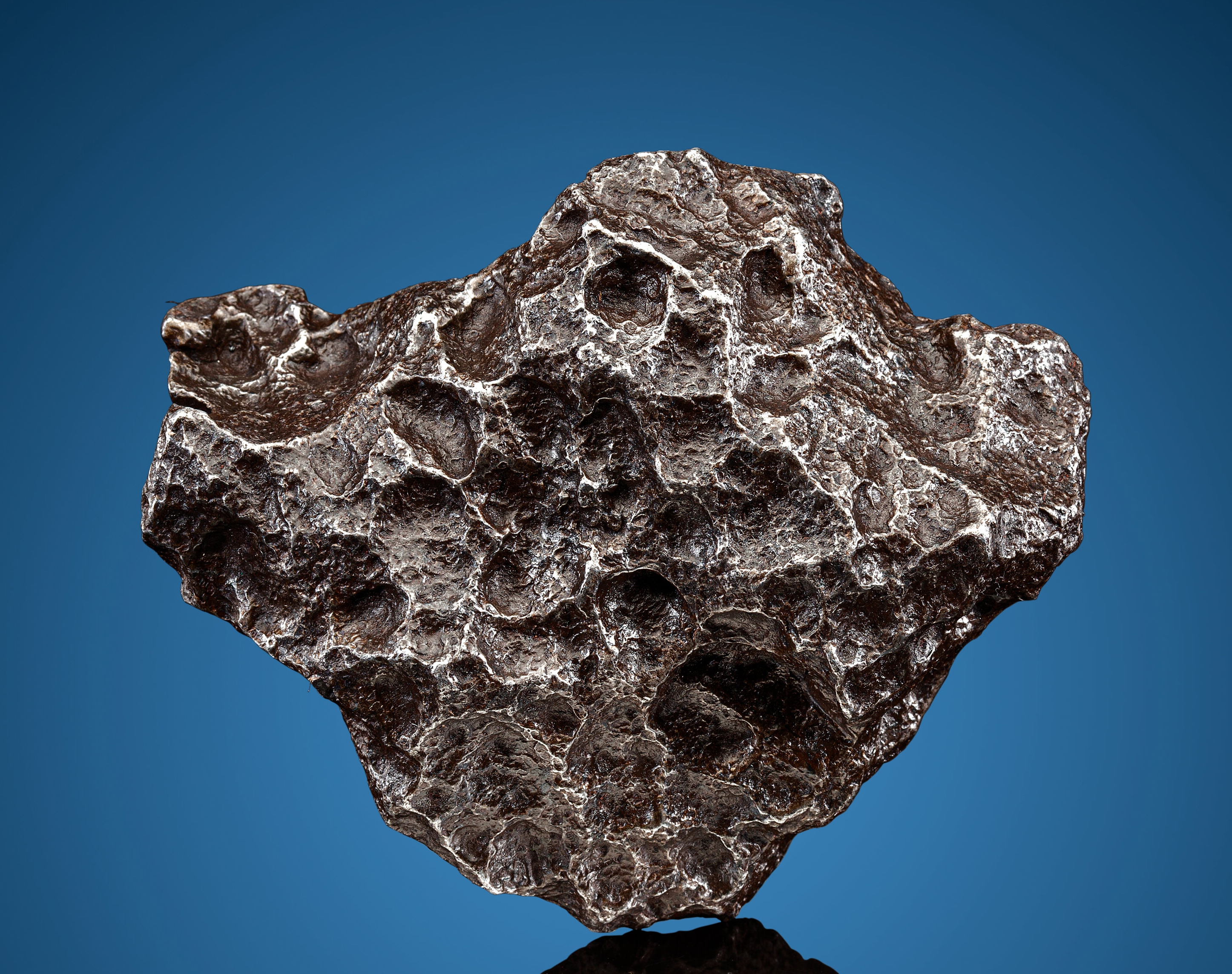

I became entirely smitten with meteorites at the age of seven during a visit to London's Geological Museum. "How could they possibly be real?" I asked myself in shy wonder. But, of course, they were real — visitors from outer space, some born in the hearts of long-dead asteroids, millions of miles away in the bleakness of space. My search for them — the remnants of asteroids that, against all odds, fell to Earth in a place where I might be able to find them — also ended up being in the millions of miles, but my journey, in comparison to theirs, was short in both time and distance.

In 1968 I promised myself I would one day have a meteorite of my own. It was the year Borman, Lovell, and Anders flew Apollo 8 around the moon. There was no network of meteorite collectors then, no meteorites for sale in rock shops, and no how-to guide for finding them. So, I set out on a mission to discover them for myself, by reading, visiting every museum collection I could get to, and by becoming an avid childhood metal detectorist. The results would eventually far transcend that little boy's dream.

Related: Hunting for Space Rocks: Q&A with Geoff Notkin of 'Meteorite Men'

It is theorized that Earth encounters thousands of asteroidal debris fragments every day. So, where are the meteorites? Space rocks fall randomly across the surface of our planet; their short, blazing flights indifferent to the equator, or the poles. The relentless power of gravity pulls potential meteorites (known as "meteoroids" until they hit the ground) through our atmosphere, super-heating their surfaces and often melting them into fantastical shapes. Statistically, the majority of incoming space rocks will sink into the oceans to be corroded away by salt water, as most meteorites are rich in iron, and we all know what happens to a pair of pliers left out in the rain.

Documented falls of larger meteorites — when "large" perhaps equates to the size of a grapefruit — are rare. We might expect less than ten recovered falls per year across our entire world, and the bulk of the extraterrestrial mass that does land is in the tiniest of pieces — settling, dust-like, onto fields, seas, forests, and even roofs.

While filming my Science Channel television series, "Meteorite Men," we investigated the 2010 Mifflin, Wisconsin fireball. Determined to find something from the dazzling spectacle seen by hundreds of eyewitnesses scattered across multiple counties and states, my co-host Steve Arnold and I made numerous trips to the fall zone, as did other meteorite hunters and scores of enthusiastic locals. Some of them met us in the field, exclaiming: "We saw your show and thought we'd give it a try!" By making a fact-based series about our work, we had created our own competition.

An exacting, almost fanatical search followed. After thousands of hours of combined field time by all parties, about 3.5 kg of Mifflin meteorites were found — the weight of a small cat. We ourselves recovered only two golf ball-sized stones. The verdict? Nearly all of the incoming mass ablated away during the flight, illustrating the difficult-to-accept concept that even a massive blazing bolide, "as bright at the sun," can pay out very little in terms of hard space rock on the ground.

If finding a meteorite after even such a widely seen event is so difficult, where should we look? It might seem that more meteorites have fallen in Texas, Northwest Africa, Chile's Atacama Desert, and Antarctica, than other places, but that is a fallacy. Those "hot spots" have yielded many meteorites because the conditions for finding them are favorable. Dry deserts do a better job of preserving meteorites and the lack of vegetation makes them easier to spot.

But Kansas was my true meteorite jackpot. Steve Arnold and I found more space rock by weight in the Sunflower State than all other sites combined and it was not because more meteorites fell there. Rather, intensive farming over the centuries, combined with a paucity of terrestrial rocks, made extraterrestrial material more noticeable. Kansas plowmen, protecting their valuable 19th century blades, went to the considerable trouble of excavating an occasional heavy rock that got in their way. Some of those rocks were substantial meteorites.

Kansas was, therefore, an enticing search location, but before digging into midwestern mud, the Meteorite Men dug through historical records. We looked for lost clues to the farmers' finds, then explored those same fields with 21st century equipment. For me, that has always been the most rewarding part of meteorite hunting: sleuthing out precisely where, long ago, a chance find was made, then revisiting the site with modern tech.

The really big meteorites — 100 pounds or more — were deeply buried, far beyond the reach of conventional hand-held detectors. So we went big too, peering ten feet into the ground with giant coils towed behind a truck. We were exercising a physical law — the bigger the detector, the deeper it "sees" into the earth. The iron content in a large buried meteorite makes a raucous sound when "touched" by a detector's electromagnetic signal, and there was nothing more exciting than the shriek of driving over a whopper.

It takes an enormous meteorite to form a crater and there are only about 200 such impact features identified on Earth. Most of those are ancient — the iron-rich asteroid fragments that created them long since weathered away. Compare with the surface of the moon, blanketed as it is with meteorite craters of all sizes, and you begin to fully appreciate our atmosphere; not just because it allows us to breathe but also because it is a shield for life — burning up incalculable numbers of meteoroids before they hit us.

My six-continent search for meteorites has been the great adventure of my life. Most finds were made with metal detectors, but some were picked up from the surface, dark and rounded, like olives off a pizza. Either way, my personal meteorite collection was decades in the making. Now, I hope these strange and beautiful visitors from space will go out into the world and enthrall others, as they have enthralled me.

While it is difficult to part with a life's work, there is always the hope of another sizable meteorite fall, or perhaps the discovery of a new crater, with twisted nickel-iron shards lying around its rim. So, I keep my best detector, spare batteries, a strong magnet, and essential field gear packed and ready in the shed. It is the career meteorite hunter's version of a bug-out bag.

"The Geoff Notkin Collection of Meteorites Signature Auction" by Heritage Auctions comprises 142 lots and is currently open for bidding. A free downloadable catalog is available, along with videos and detailed photographs. The auction culminates in a live floor session at 12 p.m. Central Time (1700 GMT) on Saturday (July 22). A significant part of the auction proceeds will be donated to children's charities, wildlife charities, and educational nonprofits.