Crime fiction is one of the most successful genres. Its titles fill bestseller lists around the world and provide hours of pleasure to its many readers – including me, a long-time fan of the form.

There are various views about why it is so popular. Many offer a variant of Aristotle’s theory of tragedy, which crime novelist Dorothy L. Sayers explains at some length and with satisfying clarity.

Aristotle argued that tragedy allows us to experience pity and terror, leading to emotional catharsis. Sayers observes, rather tongue-in-cheek, that reading crime fiction similarly provides us with a safety valve for our heated emotions: in reading about fictional violence, I will be less likely to commit actual violence.

More seriously, Sayers notes that crime fiction incorporates “an inner rightness”, because it enters a society that is under assault, and following the investigation, it restores order to the community.

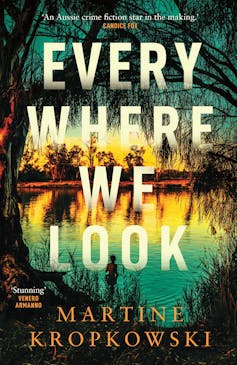

Review: Everywhere We Look – Martine Kropowski (Hachette)

Australian novelists have taken to crime writing with great relish, and Australian women writers are leaders in the field. Their stories are located sometimes in gritty urban environments, but equally – or even more frequently – are set in regional and remote Australia. “Outback noir” is so popular that it has been termed “a global publishing sensation”.

Into this field emerges Martine Kropkowski. The opening chapters of her debut novel Everywhere We Look gesture toward the outback noir tradition. The story begins in January, the start of the school year, with four mothers buying school supplies for their children, meeting each other and forming friendships.

Then the story moves out of the city. One of the four, Melissa, is driving alone through a dark pine forest to meet her friends for a country weekend. A kangaroo leaps across the road. When she swerves to avoid it, she ends up with a flat tyre and no phone reception to call for help. The nuts holding the wheel in place are almost immovable. As she struggles with them, she hears something in the forest. There’s the sound of feet, a flash of light, a foul scent, and then … is that someone giggling?

So far, so appropriately Gothic and outback noir-ish. Melissa is rescued by two men who arrive in a vehicle and help her with the tyre change. But their assistance comes with a side serving of menace. “I’m not the killer from Wolf Creek”, says the older man, a reassurance that only enhances his serial-killer appearance.

Waiting for Melissa in the rented holiday house is Bridie, who is not having a great time. She misses her baby and her wifi connection, and is frightened by her own Gothic encounters in the dark. In her case, it is a frogmouth owl in the forest, calling out in a note that “reminds Bridie of the evacuate tone at […] school. Evacuate now. Evacuate now”.

Cassandra, the third of the friends, is blunt, impatient and extremely capable. She is untouched by her friends’ rural anxieties. In fact, she deliberately chose this cottage in an isolated town because there is no phone reception and her (recently ex-) husband will not be able to “ruin this trip for her”.

Also waiting for Melissa is the town and its population. Each is precisely what and who we would expect from a rural crime-fiction setting. The members of the community are overtly quite friendly, but with a menacing undercurrent marked by an air of secrecy and scorn for city folks. The environment, too, is double-edged, combining a stunning beauty with an unwelcoming – indeed, downright dangerous – quality.

A touch of the uncanny

All of this makes for an excellent start to a crime thriller. It offers most of the ingredients we expect. It sets up the reader for the building of tension, the identification of the criminal, and the restoration of order that the genre delivers.

But having established its credentials, Everywhere We Look moves away from the obvious. The novel lacks an initial crime, lacks a detective character, and has far too many Gothic elements to be properly classified as realist crime fiction. In fact, it is as much ghost story as crime story. The country town has its own ghost – Ol’ Joe – who is described as a “famous bushranger from the 1800s”. But as the three women learn later, Ol’ Joe is a much more recent ghost: the product of violence rather than myth.

And there is a second ghost: the absent fourth member of their friendship group, Sarah. She is with them, but only in form of a shadow at the corner of the eye, a brief glimpse of a head or turn of shoulder that might be her. She is not there; she is all too much there.

When the women visit the local pub, the bartender seems to count four heads in their group. He directs them to a table that has four chairs, brings their bottle of champagne with four flutes. They tell him to take away the fourth glass, but the extra chair remains, empty and haunting.

The uncanny is never far away in this place. It appears in the form of a symbol they see graffitied on walls and fences and inscribed on the wrists of the young people. When Melissa, Bridie and Cassandra leave the pub and fall in with some of the local youths, a girl draws the same symbol on their wrists. It is to protect them, she says, “from what lurks in the Marcoy streets after dark” – which even pragmatic Cassandra admits “gave me the creeps on the long walk home”.

A swerve into something else

It is really at this point that Kropkowski’s novel swerves away from the conventions of crime and Gothic fiction into something else.

The next morning, the unnameable menace seems to be dissipated by the most practical of explanations. Terror is dispelled by relieved laughter – dispelled, that is, until they are driving back to their cottage. They see Maggie, the teenager who had marked their wrists with the protective symbol. She is hitchhiking. Just as they stop to help her, a ute pulls up and a man hauls her into the cab. They intervene, but to no effect. The woman with him assures them that Maggie is their daughter and everything is okay. But it does not look okay.

Everywhere We Look is a novel that confronts the issue of the lack of societal support for women and girls facing intimate abuse. The three friends are angry and anxious about Maggie, because what they observe looked like domestic abuse. Yet Bridie thinks, “what could we do? Sometimes shit just happens and you have no other option but to go on with your life.”

Then they hear that Maggie has gone missing and the town is mounting a search for her. And then we learn about Cassandra’s childhood, characterised by a father who exercised coercive control over his family. And then, through a narrative flashback, the setting changes to the city and a memorial service. Cassandra’s husband says: “He always seemed like such a good bloke”. In the memorial pamphlet, Cassandra reads: “All the perpetrator asks is that we do nothing”.

In the acknowledgements section at the end of the novel, Kropkowski writes: “This novel is largely a story about friendship”. Threaded through the narrative is, yes, friendship, but also a powerfully posed question: what are our responsibilities as members of a community? Can we step in when something is clearly going wrong? How can we do that, who are we letting down, and what rules are we breaking, if we intervene, or if we do nothing?

These questions animate Everywhere We Look and they cut deep. I found the novel’s turn away from the conventions of crime fiction into a story of intimate violence shocking, and profoundly moving. I won’t give away the complexities of the narrative and its ending, except to say that, as the story reaches its denouement, there is a glimmer of light: the possibility of imagining “an outcome a little less hopeless”. That is a possibility worth imagining.

Jen Webb does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.