It has been more than four decades since the founder of modern China died, but Mao Zedong-style calligraphy is still very much alive – and President Xi Jinping is apparently a fan.

According to Qian Gang, director of the China Media Project at the University of Hong Kong’s Journalism and Media Studies Centre, the Chinese leader has even “fashioned his signature in the Mao Zedong calligraphy style”.

Qian made the observation in an article headlined “Keeping to the script” on the former chairman’s writing style, published on the China Media Project website on Sunday.

Mao’s handwriting was known to be somewhat unorthodox, with the Chinese characters often slanting to the right.

Chinese Marxist student leader taken away by police on 125th anniversary of Mao Zedong’s birth

Xi is not alone in adopting the distinctive style – it has been used in recent state media productions, and China has since 2017 held an international competition to imitate Mao’s writing.

Calligraphers such as Li Yiming and Li Minghe have also made a name for themselves by following Mao’s lead with a brush and ink.

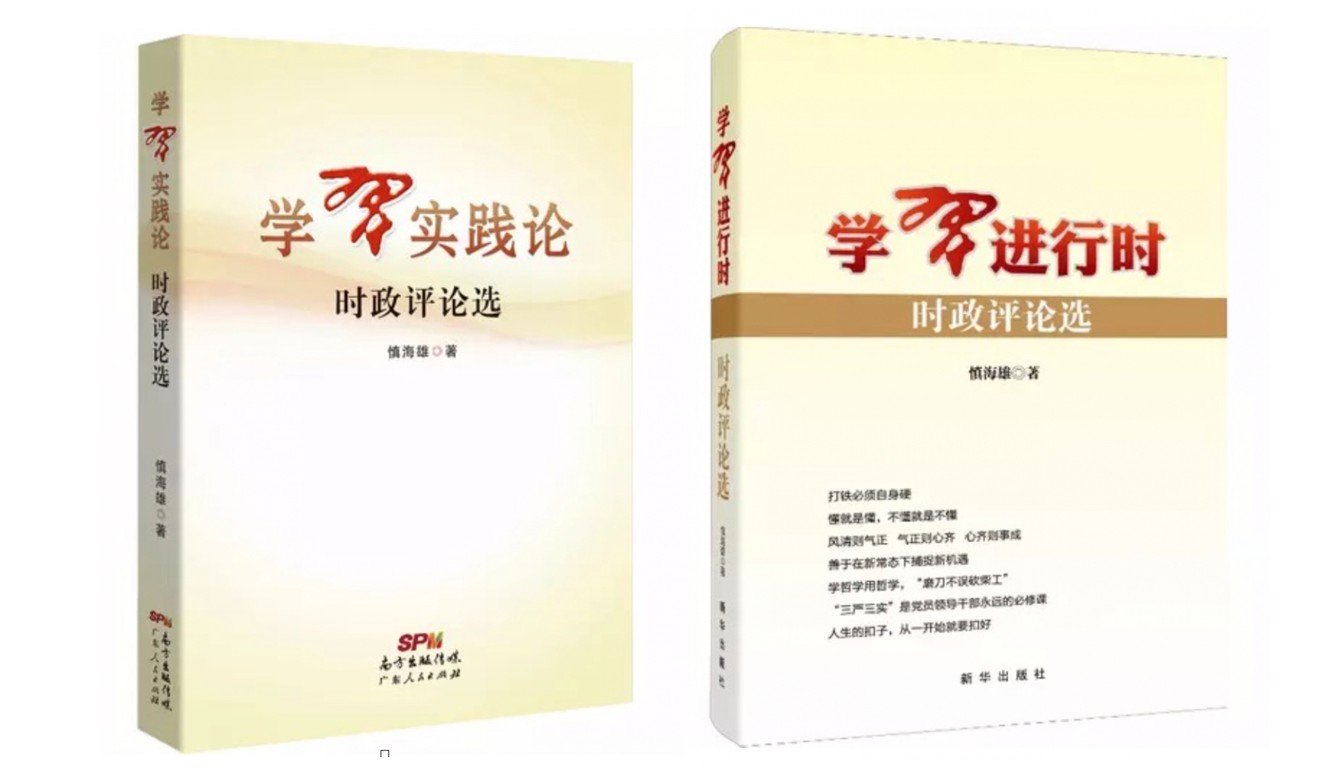

In his article, Qian said he first noticed Xi’s Mao-style signature earlier this year, when he saw the covers of two new books written about “Xi Jinping Thought”, the president’s political theory.

Written by Shen Haixiong from the Central Propaganda Department, the titles of both books – Views on putting Xi study into practice and Studying Xi in the present – play on the character “Xi”, which as well as being the president’s surname can also mean “practice” or “study” in Chinese.

Both use a distinctive version of the “Xi” character, and Qian suspected it might have been the president’s own handwriting.

Why Xi Jinping should learn from Chiang Kai-shek, instead of modelling himself on Mao

He then examined a letter written by Xi to recent college graduates in 2014, noting that the character for his surname was signed with the same flourish seen on the book covers.

Qian said another letter written two years later to Hung Hsiu-chu, then chairwoman of Taiwan’s Kuomintang, confirmed his theory – it was Xi’s signature on the book covers, and it was written in Mao’s style. He said the distinctive form was also seen in the president’s handwriting that is used extensively by state media when reporting his quotes.

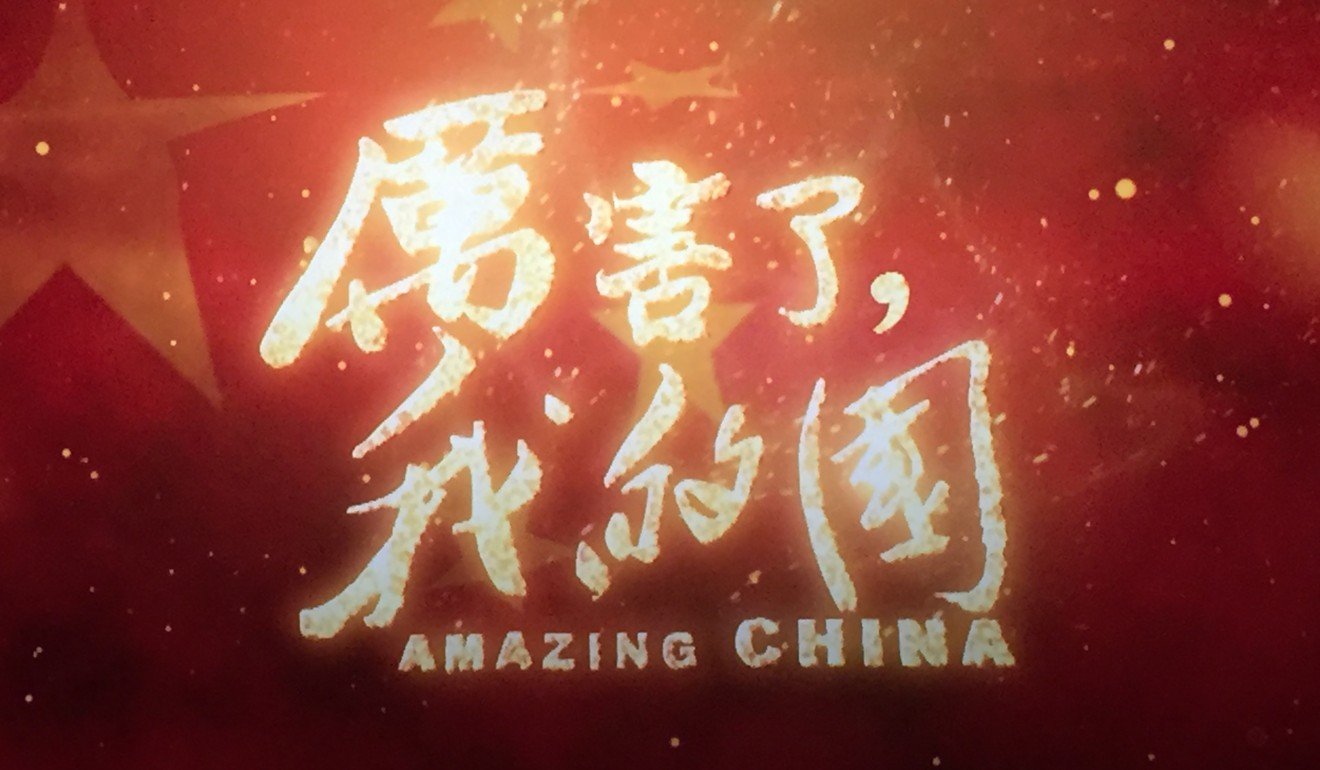

The calligraphy style has also become more popular in programmes on state media. For example, Mao-style characters were used for Amazing China, a recent CCTV documentary lauding China’s economic and technological achievements.

These characters can even be produced online by a “Mao script generator”, which draws on a vast catalogue of the former chairman’s handwriting to create words and phrases inputted by the user.

But Qian questioned whether it was appropriate to use these fonts in documentaries on reform that are supposed to be all about the “transformation away from Mao” and the “repudiation of the suffering and damage” Mao inflicted on the country.

Mao’s legacy includes the Cultural Revolution, a decade of violence and upheaval that began in 1966 and ended with his death in 1976.