In 1992 teacher Sheryl Leach created the gentle purple dinosaur character in order to entertain her toddler son Patrick. Thanks to her marketing creativity, going from video store to video store, "Barney & Friends" became a childhood staple, teaching kids how to sing, love one another and be happy. No one expected that Barney would become a figure of infamy.

Peacock's new two-part docuseries "I Love You, You Hate Me" explores the cultural phenomenon that was Barney the Dinosaur, and the resulting backlash from adults who nurtured anger and criticism around him. From Barney-bashing frat parties and hate groups to violent video games, Barney lived rent-free in adult minds, a squatter who inspired contempt and revulsion. Unfounded rumors – ranging from Barney acting as a drug mule to acting inappropriate with children – unfairly maligned the character, and even the San Diego Chicken mascot famously staged a Barney beatdown during one game.

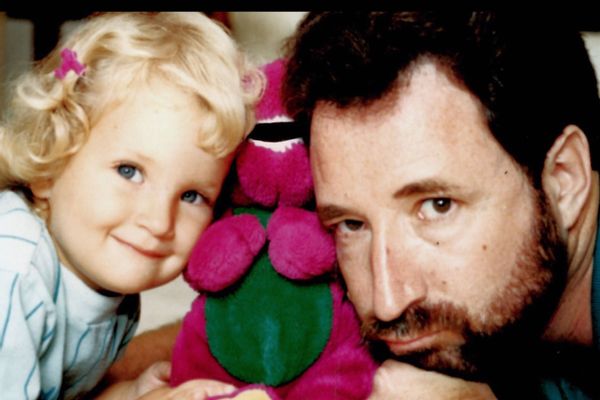

But perhaps the most horrifying fallout was the toll it took on those closest to Barney. Bob West, who voiced the dinosaur, received death threats. Leach's marriage supposedly fell apart from the amount of time she spent focused on Barney, often calling him her "other child." Most of all, her son Patrick grew to resent that purple sibling, and as the show implies, this turned him down a dark path.

"I Love You, You Hate Me," directed by Tommy Avallone, speaks to the people who contributed to "Barney & Friends," those closest to the Leaches, leaders of hate groups and pop culture commentators to get a bigger picture of what Barney ultimately meant to America.

Executive producer Joel Chiodi spoke to Salon about putting together "I Love You, You Hate Me":

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What drew you to Barney story and inspired you to put together this docuseries?

We're working with the director Tommy Avallone who who had an idea for it. But I wasn't part of the Barney generation. I was just prior when it was just PBS Saturday and "Sesame Street" and, and all those shows along with Saturday morning. And so I missed that moment when it was Barney and Nickelodeon and all the things that came afterward. And so and I was always just really fascinated by the character. But then when we opened it up, there was so much more there. It wasn't just this nostalgic piece, but it was also this thing about the dawn of hate and the ingenuity of Sheryl Leach who created Barney against all odds. I just think we're in that '90s nostalgia moment, and it feels like Barney was such an iconic piece of that. And I just love how there's connectors to what's happening today with how we live in social media, and I think it's a great precursor and can teach us so much about the moment we're living in now.

Who were the participants that were the hardest to get ahold of for the docuseries?

"I feel like we really tried to do Barney justice."

Like any family, there's allegiances and friends and fallout and all of that. Without naming any names, there were certain people who were like, "I'll do it but not if this person does it." Even within the people who play Barney. So to get everyone on board, which we did – except for Sheryl and her son, obviously – it was more about assuaging everyone because everyone wanted to have their own rules about who got to participate. I think it was important for us to make sure everyone had a voice.

Are there any additional participants that you wish you got in touch with or could have featured in the series?

Obviously I would have loved to have Sheryl. I would have loved to have Sheryl's son, and I would have loved to have other family members. I think we did them justice. My mom's a teacher so I felt a special affinity to her. And I think as you can see, because she's somewhat litigious, not to us, but to to anytime anyone's sort of denigrated Barney. We end up with, it really hasn't been a love letter, but we show all the the drama that happened in front of the screen, and behind the screen and in the culture. I just think she just really wanted to preserve Barney without an acknowledgment of everything around it. But my hope would have been that she would have come on board because I feel like we really tried to do Barney justice in the whole thing.

I love this naivete of Sheryl who didn't know what it would take to do this and was not fearful or intimidated. Everything down to finally getting this production made, she'd spent all the money on the production. So there was no marketing. And so she went from Blockbuster to Blockbuster, and would have these endcaps where you see the VHS tapes and that's how this thing became a hit. She just made it happen.

I think very important. There was a young Asian cast member [Pia Jasmine Hamilton, who played "Min."] I didn't realize all these mini stories that we're going to be reflected. You hear the big ones about hate or this guy who was on "Jerry Springer" about this fight or that. But there's these little micro stories, like we hadn't seen Asians on camera in that way and how that informed not only this girl but the people who watch the show, this visibility moment. It's just so heartwarming and informing this moment where we talk about wokeness and we talk about these terms . . . without even really understanding what they mean. There's so many stories to be told, and that when people see a version of themselves on screen, how that impacts them. It felt in some ways like closure for the cast where they finally got to reconcile it and bookend the most dominant thing in their their lives.

While making the series and doing research for it, what are some of the most bizarre stories that actually surprised you?

For me, there is a juxtaposition of the teacher [creating Barney] for her son to entertain him because she didn't see something on the air. Totally innocent. And yet these stories of –there's cocaine in the tail of Barney the Dinosaur, or questions of a whiff of inappropriateness in his behavior. The cocaine thing really freaks me out because normally you could say oh, that was sort of extrapolated from some weird thing about our culture. But then there's certain things that are such a leap. You're like, "Well, how would that even be generated?" I found that particular one to just be absolutely bizarre.

I thought this bit was incredibly entertaining where the series interviews the San Diego Chicken about his fight with "Barney" during a game, and how that sparked a lawsuit where ultimately, it was ruled as a bit of parody. Can you discuss the way the San Diego Chicken got involved with this project? And also, how did you have him be in character as a talking head?

We've only seen the San Diego Chicken in character. I don't know what he looks like. No one has seen him, and I think it ultimately it fell in our laps. That trial with Sheryl and, the production suing the chicken for defamation, all of that, it feels like a key part of the story. Up until then, you're seeing a production and a person who's built something and hits this zenith, there's a little bit of a backlash, but them not knowing really how defamation works. All of a sudden they turn into the big company and the bad guy who's against free speech. And it's a moment I think, where it adds to the – don't try and stop us – the sort of dawn of online culture where it's all about anyone gets to talk about whatever they want. And so she and the production look like an oppressor of that, and Barney becomes the face of it. Having the Chicken . . . I think he's really proud of, as I think you've seen the documentary, the precedent he helped establish about parody and free speech.

"[Barney]'s kind of got a gay voice and ... challenges our tropes about masculinity."

In this digital world that we live in, it's so funny to hear about, "I'm going to start a Barney hate club. Send 75 cents and a self-addressed stamped envelope and you will get our newsletter." It just feels like such a different era of time. I think as the father [Robert Curran] was just annoyed with having to listen to that thing all day and then as a divorced father, where you only have every other weekend or whatever. So I think for him, it felt like a lark that turned into something. He ended up getting sober. He realized it wasn't about [Barney]; it was about something else in his own life. And it feels really apologetic, like, "Oh, I can have a little bit of fame and leverage it for a moment," not realizing perhaps, the toxicity of the bad way he was throwing gasoline on the fire.

[Sean Breen], I wasn't in that interview, but my sense of it is is he's just very contrarian and I don't think he had a change of heart. But like, I don't again, I personally didn't oversee that [interview].

Were there any specific challenges when addressing Patrick Leach's story specifically the attempted murder and also the subsequent charges? Because I know overall that is an incredibly sensitive story.

There's the "I hate you" part of it. You hate this thing that is actually really innocent; there's nothing behind it. It's almost like we're not capable – unless there's drama or tension or conflict – we can't just let something be pure.

Sheryl created this dinosaur to entertain her son and she calls Barney her other child. And ultimately, Patrick resented the time this dinosaur was taking his mother from him. Ultimately, she ends up walking away but by that time, it seems like the damage is done. We didn't want to be salacious about it . . . but there is a ripple through Sheryl's life between what happened with her ex husband and and her child. You know everyone thinks when you have success and when you have money that it will solve the problems, but sometimes it just magnifies them.

In the documentary, Patrick Leach's babysitter does an interview and then returns two months later to add to her story, giving more insight into Patrick's personality as a child. What was that process like? Did you and your team reached out to Lori Wendt specifically or did she come forward on her own to clarify and also add to her story?

So we reached out, we felt like she was a critical interview. Her first interview was just OK; she didn't really go there. And so we left it, we had enough to actually help tell the story, but she actually called the director Tommy and said, "I didn't do this right. If I can do it, I'm gonna do it." She actually came to us. There was a pre-interview and follow-up that happened, and then we felt like it was worth it based on what you knew her to say. And that led to the second interview, and I think a very dramatic moment in the documentary.

You didn't grow up in the era of Barney but would you say that you're a Barney lover or Barney hater, or just overall neutral about your feelings?

I would say two things. I'm from the "Sesame Street" era. So I'm more a fan of Snuffleupagus and Big Bird. And I have a bit of suspicion about anything that's children's for profit, like a Nickelodeon show or Barney show or the Power Rangers because they're always marketing to the kids and it's less educational or learning how to deal with grief or love or how to add or spell. It feels like a vehicle to sell. So I'm slightly anti-[Barney] in that way.

"Take a deep breath and remember underneath it, it was just a little dinosaur."

But the thing I love the most about Barney is that right around the time Barney was being created – I get to say this as a gay guy – he's kind of got a gay voice and he's got the sort of not as masculine hands and bounces around in a way that challenges our tropes about masculinity. We are here with something that blew up with a ton of hate and was very divisive with "Jerry Springer" and the talk shows and all of that. And the thing that is traditionally masculine, like a "Jurassic Park," we're still making sequels for to this very year. So what I love about Barney . . . as a person in the LGBTQ community, it is like someone who wants to be able to continue to learn. He poses challenging questions about masculinity, about our culture, about how we talk to one another, conspiracy theories and the nature of what our our discourse has become. And for that, I love it.

What do you hope audiences will take away from this documentary?

First of all, I like to call it chocolate-covered spinach. It's super entertaining. This time that we live in, to have a little bit of lightness and fun, let's take it right. But I hope that we can learn something too. And there's so many lessons I don't want to spoil people's sense of discovery and what that might be.

For me, it was really about what do I want to focus on – the positive or the negative? Now that this is blown over we know there was no cocaine in the tail. We know all these sort of nefarious things people thought weren't true. There was a teacher making something for her kid. It blew up in a way no one expected and made a lot of money and it made a dent in our pop culture. And everything beyond that is bulls**t. So at this moment we live in it's something that we can take with this – as the news cycle continues on and people rage about elections and what's right and what's wrong – which is just to take a deep breath and remember underneath it, it was just a little dinosaur.

"I Love You, You Hate Me" is available to stream on Peacock.