Christopher Wheeldon and The Australian Ballet’s Oscar, which had its world premiere in Melbourne on September 13, is based on the story of Oscar Wilde: the writer, the man, the protester.

Combining key life events with two of Wilde’s well-known works – The Nightingale and the Rose, and The Picture of Dorian Gray – Wheeldon has created a complex and highly cinematic ballet about a literary genius who was also a gay martyr.

Wheeldon has also delivered on something I think has been long overdue: a gay ballet.

Act one: memories of happier days

The first act begins with Wilde’s trial and conviction for committing sexual acts with men.

From his prison bed, we see the memories of love that flood his mind. We see him happy with his wife Constance and their children, and attending literary and social occasions. We see memories of his favourite female actors, as well as his introduction to his best friend Robbie Ross and the secret world of gay men.

These stories are segmented; the scenes cut from one to another, as well as to the unfolding tale of Wilde’s nightingale and her futile sacrifice and death for love.

These are the mixed-up memories of a man facing the horrific consequences of standing up for a forbidden love. In them we see a world where Wilde was successful and happy. In his iconic suit and waistcoat, he is the Oscar Wilde we know.

But this is a man only beginning his prison time.

Act two: the horror sinks in

In the second act we see Wilde deep into his two-year sentence, lying on the floor of his cell. Isolation, malnutrition and hard labour have destroyed him both physically and emotionally. He is remembering his relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas that ultimately led to his conviction and imprisonment.

Again, the scenes are cut and interspersed with other scenes from the trial, of his family, his friend Ross and the nightingale. They are also set next to pieces of the story of Dorian Gray, in which Wilde and Douglas at times replace Dorian the man and Dorian the decaying portrait.

In act two, Wilde is a broken man. The memory scenes are seedier, darker, and more debauched and threatening. Sex largely replaces the romantic and platonic love of the first act. We see dimly lit illegal gay sex scenes and cavorting in cabaret clubs. Wilde stumbles through the act in his dirty dark green prison uniform.

An ‘out’ ballet

Wheeldon and The Australian Ballet artistic director David Hallberg have described Oscar as the first “out” gay ballet.

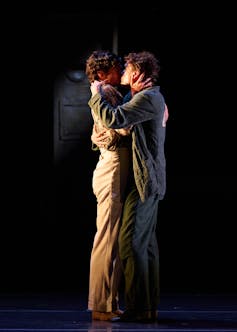

In act one, a near-kiss prepared us for what was to come in act two, two men kissing on the ballet stage. In the program, Wheeldon states both he and Hallberg, as gay men, felt a gay ballet narrative was overdue and that the time was right to make one.

But what makes Oscar a gay ballet? Is it the heroic narrative about an historic gay figure? Is it two men kissing for perhaps the first time on an Australian ballet stage? Is it because it is made by gay men who themselves have called it a gay ballet?

Yes, it’s all of these. But it’s also more than that.

As Hannah McCann and Whitney Monaghan suggest in their book Queer Theory Now, the term “queer” is used to describe not just the slipperiness of categories and boundaries of gender and sexuality, but also of more general categories and boundaries.

In Oscar, there is a slipperiness of the category of ballet. The movement vocabulary in the ballet draws from multiple forms of dance. Music theatre, for instance, has a strong presence in one courtroom scene in which chairs and benches are being manoeuvred in formations.

There is classical ballet, such as with the pas de deux between Oscar and his wife. There are contemporary lyrical pieces, including Ross’s solo which opens the second act. There is a touch of Russian constructivism with geometric arm shapes, mechanised jerky movement and fixed mask-like facial expressions.

There is even a little vaudeville, with cancan and cross-dressing – as well as some sassy Balanchine-esque moments of contemporary ballet with slides and swings, strong geometries and slightly cocked hips.

This melange applies equally to Joby Talbot’s score. It moves from classical, to jazzed up, to recorded sounds, to techno.

Jean-Marc Puissant’s costumes also follow the trend. While traditional rich Victorian clothes are worn in the historical scenes, the costumes in the nightingale story are brightly coloured and flamboyant, some with Wilde’s handwriting printed into the fabric. Wilde’s simple prison uniform is much like pyjamas.

Oscar is a pastiche of forms of dance, music and design unapologetically and abruptly juxtaposed across a splintered narrative that cuts like a piece of cinema from one scene to the next. It is Swan Lake meets Baz Luhrmann, Moulin Rouge meets the Brothers Grimm.

At the start of opening night, Hallberg warned the audience they might be shocked. Perhaps some were, but the standing ovation at the end suggested this was a much-loved and welcomed ballet.

Oscar is showing at the Regent Theatre, Melbourne, until September 24 and at the Sydney Opera House from November 8 to 23.

Yvette Grant does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.