The pyramids of Egypt have long captivated our imagination, with some even believing the magnificent structures harness magical or healing powers. In 1978, masters of the concept album The Alan Parsons Project explored themes of pyramid power and ancient magic on their third studio album, Pyramid. Prog and Parsons step back in time to uncover the story behind the group’s Grammy-nominated and recently-reissued record.

If you were around in the 1970s you may recall seeing dinky metal pyramids sat on top of milk bottles. During a short-lived craze, the pyramids were pitched as power directors which could stop your full-fat turning sour.

The idea first appeared in Lynn Schroeder and Sheila Ostrander’s 1970 book Psychic Discoveries Behind The Iron Curtain, which served up its mysticism with a side of Cold War paranoia. According to its authors the Soviets were harnessing pyramid power to preserve milk and food, thanks to the psychic energy generated by the four points of a compass.

The science was questionable to non-existent; but that didn’t stop the devices finding their way into household fridges – and inspiring Pyramania on The Alan Parsons Project’s third album, 1978’s Pyramid. Not that the band’s figurehead or his co-writer/manager Eric Woolfson believed the claims made in the book. “But there was certainly something in the air,” says Parsons. “We’d all sit around late at night, talking about life and the universe.”

Pyramid was recently reissued as a box set, containing multiple outtakes, Woolfson’s demos (known as ‘songwriting diaries’) and a Dolby Atmos mix. Pyramid continued the group’s exploration of otherworldly themes, pioneered on their 1976 Edgar Allan Poe-inspired debut Tales Of Mystery And Imagination, and the following year’s Isaac Asimov-themed Top 30 hit, I Robot.

However, Pyramid also threw in some wry cynicism; and spliced its art-rock with filmic instrumentals and the radio-friendly single What Goes Up. Work on the album commenced in summer 1977 at EMI’s Abbey Road studios, where Parsons had first been employed as a tape op, before helping engineer The Beatles’ Abbey Road and Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side Of The Moon.

He’d just produced folk progger Al Stewart’s The Year Of The Cat and hits for John Miles and Scottish pop-rockers Pilot, and was feeling frustrated when he encountered another Scot, Eric Woolfson, at Abbey Road. “I’d been involved with two consecutive No.1 records but I didn’t seem to have any money,” Parsons explains. “I decided I needed a manager. Eric and I met in the canteen at the studio and he fitted the bill.”

Woolfson had just struck gold managing Carl Douglas of Kung Fu Fighting fame, but he’d spent most of the 60s composing for the likes of Marianne Faithfull and The Tremeloes. A prolific songwriter and lyricist, he had a batch of songs based on the work of 19th-century horror icon Poe looking for a good home.

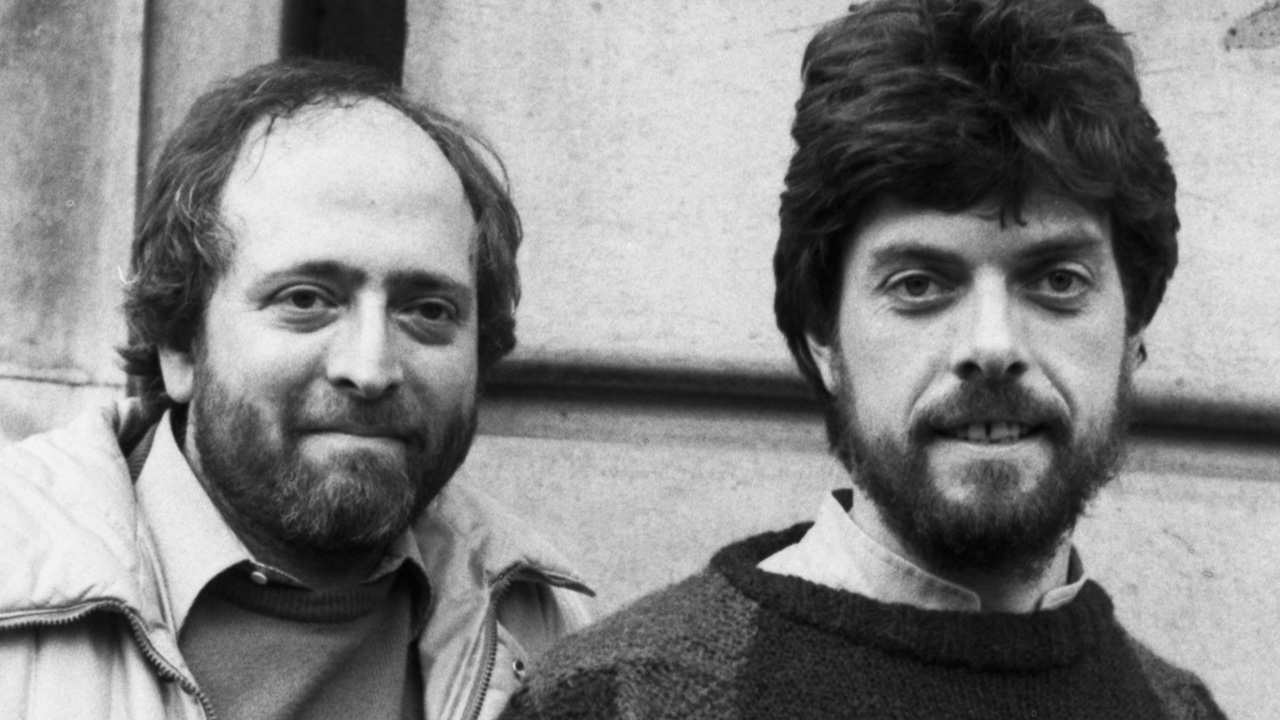

Parsons, who’d previously played in folk and blues groups, partnered with Woolfson on both a business and musical level, but Woolfson wisely agreed to name the project after the Grammy-nominated engineer since it carried more commercial weight. After Tales Of Mystery And Imagination received several glowing reviews, record mogul Clive Davis signed The Alan Parsons Project to Arista, where they remained for the next 10 years.

Honestly, I’m not entirely sure we’d visited Egypt before we made the record

In the essay accompanying the Pyramid box set, Woolfson (who died in 2009) is quoted as saying the duo created music “in the same way that Stanley Kubrick or Alfred Hitchcock made movies – where the directors, rather than the artists, were the focal point.” Songs based on Poe’s gothic horrors and Asimov’s futuristic adventures appealed to the same demographic that had pored over the sleeve of The Dark Side Of The Moon, and APP cultivated a similar mystique by not appearing on the covers of either album.

I Robot chimed with the times: the title appealed to American audiences in thrall to R2-D2 and C-3PO, the cybernetic Laurel and Hardy from new hit movie Star Wars. The album went Top 10 in the US, enabled by the hit I Wouldn’t Want To Be Like You, sung by Lenny Zakatek from British funk-rockers Gonzalez.

All this established the Project’s modus operandi going into Pyramid: literatary themes, crafted music and a keen pop sensibility – prog rock with big choruses, then. But the album wasn’t meant to be about pyramids to start with. “Originally, Eric and I said, ‘Let’s make an album about witchcraft,’” Parsons recalls. “But I supposed pyramid power was a sort of witchcraft, so we zeroed in on that instead.”

They definitely weren’t writing from personal experience. “Honestly, I’m not entirely sure we’d visited Egypt before we made the record!” he admits. “I did take my family there and do the tourist thing, but I think that was later. Then again, I didn’t go to see La Sagrada Familia [church in Barcelona] until after the Project made the Gaudi album [in honour of its architect] in 1987.”

Eric, especially, always liked the idea of film music

For Pyramid, the duo’s core band of guitarist Ian Bairnson, bassist David Paton and drummer Stuart Elliott were joined by arranger Andrew Powell; vocalists Dean Ford, the Zombies’ Colin Blunstone, John Miles and the English Chorale choir; an arsenal of pan pipes, church bells and a Finnish stringed instrument called a kantele.

They also used Abbey Road like another band member. “The studio helped shape the compositions,” Parsons explains. They block-booked their room, 24 hours a day, for a total of eight weeks. Poacher-turned-gamekeeper Parsons had learned from watching Lennon and McCartney and Gilmour and Waters; so the project leaders were obsessive in their pursuit of the perfect take. Spending 14 hours on a backing track wasn’t unusual, with Woolfson directing from his piano and Parsons behind the console.

When cabin fever set in, they downed instruments and repaired to Woolfson’s favourite restaurant, Keats, in nearby Hampstead, for chateaubriand and a decent claret. (The eatery’s name inspired a Project offshoot featuring some of the band and Colin Blunstone in the early 80s.)

Many of the tapes were labelled with fake songtitles. One More River became ‘Old Man River’ and The Eagle Will Rise Again was listed as ‘Amazing Gracie.’ “It was partly so the actual titles didn’t get leaked to the press,” says Parsons. “But also to keep ourselves amused, and keep the band guessing.”

The instrumentals Voyager and Hyper-Gamma-Spaces sound like incidental music from a great lost sci-fi movie; while In The Lap Of The Gods suggests Ben Hur meets The Omen. Elsewhere, The Eagle Will Rise Again and Shadow Of A Lonely Man could be themes from a big-screen 70s weepie.

“Those sorts of pieces were always part of the Project sound. Eric, especially, always liked the idea of film music,” says Parsons. He was coaxed into recording a lead vocal for Shadow Of A Lonely Man before calling John Miles instead. “Mine wasn’t that bad, but it wasn’t that good either,” he explains.

The shoot was agonising. All the photographers and prop people were wearing gloves, scarves and heavy clothes

As fascinated as Woolfson was by the pyramids and their mythology, neither he nor Parsons were above having fun with the subject. Hyper-Gamma-Spaces borrowed its title from a thesis by Woolfson’s scientist brother, while Pyramania addressed pyramids on milk bottles or “under my bed... in any possible location.”

Parsons has an intriguing relationship with the supernatural. He was a member of the Magic Circle, and is currently a member of its American equivalent, the Magic Castle. It runs in the family – sort of.

“My father worked with the Society For Psychical Research, and his company explained what [spoon-bending TV magician] Uri Geller was doing. I was impressed by Uri Geller; he was a good magician, but he was just putting people on. So I have always been a bit cynical of anything supernatural.”

This wry take on the subject extended to the album sleeve, shot by Hipgnosis, showing Parsons sat on a bed holding his head in his hands while lysergic vapour trails emanate from his body. Was it fun? “No. It was December in a cold photographic studio and I was wearing a pair of paper-thin pyjamas,” he divulges.

The set embraced the theme by including a copy of G Patrick Flanagan’s bestseller Pyramid Power: The Millennium Science, and an alarm clock set to 3:14, referring to the mathematical sign pi, which is roughly 3.14. “That was my idea,” recalls Parsons. “But the shoot was agonising. All the photographers and prop people were wearing gloves, scarves and heavy clothes.”

I am not, and never have been, a frustrated rock star… but I never guessed how much fun I’d have playing live

Pyramid was released in May ’78, by which time Woolfson’s business acumen had led him and Parsons moving their families to tax-haven Monaco, just in time to enjoy that year’s Grand Prix. While the album made the US Top 30, it didn’t quite scale the heights achieved by I Robot. Not that Parsons seems concerned.

“I like the album and it’s been a pleasure revisiting the demos and hearing some of these alternative versions,” he says. “But we were definitely being encouraged by Clive Davis to make more commercial music, which eventually led us to [1980’s] The Turn Of A Friendly Card.”

After that The Alan Parsons Project scored their biggest hit with 1982’s Eye In The Sky, and continued to release music until creative difficulties derailed the partnership in 1990. The Pyramid box set has been produced with the hands-on involvement of Woolfson’s family. “Put it this way, there were fewer conflicts then than there are these days,” admits Parsons. “Eric’s passed away, but we have a lot of unfinished business.”

After the split, Parsons was persuaded to take the Project’s music on the road for the first time in 1993. “The trouble is, The Alan Parsons Project was only intended as a studio venture. That’s why we never considered how difficult it would be to recreate a huge orchestra and endless overdubs live. I never anticipated we would be onstage. Ian Bairnson convinced me that my guitar playing was good enough to be a rhythm guitarist in the band. And here we are today.”

At their show in Nashville on the current Alan Parsons Live Project tour, they performed Can’t Take It With You and What Goes Up from Pyramid. The mastermind sat on a podium, overseeing proceedings, resembling a magician with his plume of dark hair and big beard. “I am not, and never have been, a frustrated rock star!” he says. “But I never guessed how much fun I’d have playing live.”

Both Eric and I preferred the anonymity. I’m still basically unrecognisable

Pyramid illustrates his personal journey from studio magus to platinum-selling muso, while he spared himself the trappings of fame and celebrity. “Both Eric and I preferred the anonymity,” he says. “I’m still basically unrecognisable.”

So much so that Parsons is certain the heir to the throne, Prince William, didn’t have a clue who he was when he awarded him with an OBE at Buckingham Palace in summer 2022. If, Prog wonders, he had to recommend an Alan Parsons Project album to the future king, would it be Pyramid?

“Er, probably not,” chuckles Parsons. “I’d say Tales Of Mystery And Imagination. We were young and innocent then and it was the beginning of everything.”