Going into this year, China had won about 20 gold medals in the Olympic Winter Games since it first joined in 1980. Seven of these medals were clinched by athletes born in Qitaihe, a poor, small town in the country’s Northeast, and all that can be traced back to an unsung hero who built it against all odds.

Two legendary Chinese Winter Olympic champions — Yang Yang, who bagged China’s first-ever gold medal, and Wang Meng, who won three gold medals at the 2006 Turin Games — are from Qitaihe.

Qitaihe, with a total population of less than 700,000 including its villagers, is a smaller city than some counties in bigger provinces. The place does not have a long history. It was merely a town under the jurisdiction of Boli county until 1958, before gaining city status thanks to a booming coal mining industry. Today, it is a place of resource depletion and economic decline, where people earn around 3,000 yuan ($473) per capita, about half of the nation’s average.

So how come so many champions have been cultivated in this scarcely populated, economically troubled city? The answer is a man called Meng Qingyu.

Born in 1951, Meng grew up in Heilongjiang’s capital of Harbin and came to Qitaihe as a sent-down youth in 1969, where he became a coal miner. Meng loved ice skating. When he set up a rudimentary ice rink at a middle school affiliated to the local mining bureau, he offered to fill it up with water and maintain it, as long as he could use it to practice.

In January 1972, he participated in a regional ice sports competition on behalf of Qitaihe and won the 1,500-meter, 3,000-meter and 5,000-meter speed skating events, setting new regional records.

Meng was invited to serve as a skating coach at the amateur sports school. Although mining brought in more money, his love of the sport persuaded him to accept the offer.

At his new job, Meng had to start from scratch. First of all, there was not a single decent ice rink in Qitaihe. He designed a simple resurfacer by fixing a big metal bucket to a sleigh, which he pulled around and around until he had created a flat surface on the ice. When he was done, his eyebrows and lashes would be covered in white frost.

Resurfacing was a job for the middle of the night, when it was pitch dark and -20 degree Celsius. He would then go back and wake his students for training. He was coach, maintenance man, and cook for the skating team. The skaters all lived together in a few shabby rooms.

Meng’s hard work paid off. In January 1985, the first national youth speed skating championship was held and 13-year-old Zhang Jie from Qitaihe’s sports school claimed five gold medals in the women’s group while Xu Chenglu grabbed gold in the men’s 1,500 meters. Both were Meng’s students.

After the stunning success, the people of Qitaihe fell in love with winter sports, with more and more primary and secondary schools building ice rinks and holding competitions. Yang Yang, 10 years old at that time, became fascinated by the sport and joined Meng’s team.

In 1987, Meng found out how popular short track speed skating had become abroad. He switched his attention to short track and never looked back. Qitaihe simply did not have a track with a circumference of 400 meters, so athletes in the longer track events had to go to the provincial gymnasium for training. Short track speed skating rinks, with a circumference of only 111.12 meters, were much easier to build.

Meng’s decision proved to be smart. In 1991, Zhang Jie came in first in women’s 1,000-meter short track speed skating at the Universiade. The following year at the Winter Olympics, Li Yan earned the silver medal in the women’s 500-meter short track speed skating event — China’s first Olympic medal in a short track event. A decade later, in 2002, Yang Yang won the gold in short track speed skating at the Winter Olympic Games, becoming China’s first-ever Winter Games gold medalist.

Meng’s next big thing was cultivating a talent pipeline. He realized that to develop outstanding athletes, it was necessary to start training them from childhood. To make this possible, he established a sports school for junior short track speed skaters.

Wang Meng, whose parents were both local miners, enrolled at the school at age 9 after persuading her parents. About 10 years later, she brought home three gold medals at the Turin Olympics.

That is the story behind how Qitaihe became the home of some of the best ever winter athletes in China. Of the country’s 1,730 registered short track speed skating athletes, 344 have come from the small border town of Qitaihe. That’s nearly one-fifth of China’s total.

Skaters trained by Meng have made impressive achievements. Over the past decades, winter sports athletes from Qitaihe have broken 15 world records and won 173 gold medals in world-class competitions, as well as 535 at national competitions.

After all the success, however, Meng did not chase fame and fortune. Instead of accepting high-paid coaching positions elsewhere, he stayed in Qitaihe, continuing his undertaking in local grassroots sports.

In August 2006, Meng died in a traffic accident at the age of 55. When he died, his family’s most valuable assets were a 40-square-meter house, an old TV and a worn-out refrigerator.

The success of California-born star skier Eileen Gu at the Beijing Winter Olympics has been the envy of countless Chinese middle-class families, making many believe that perfect material conditions, outstanding parents and an excellent education are prerequisites for success. But in my view, you don’t need money to become a champion. The vast majority of households, and even societies, are unable to replicate an elite sports model, and the emergence of stars like Gu is highly accidental. When it comes to winter sports, the “civilian sports model” that Meng spearheaded in Qitaihe is of much greater value to the nation.

What Meng promoted shows that even in places with poor economies, you can still achieve success by mobilizing society’s enthusiasm to play sports and cultivate a talent pool. Internationally, there are countless examples of athletes who have grown up in slum conditions and still made it to the top. This shows how important it is to arouse enthusiasm for sports at grassroots level and encourage children to find their passion.

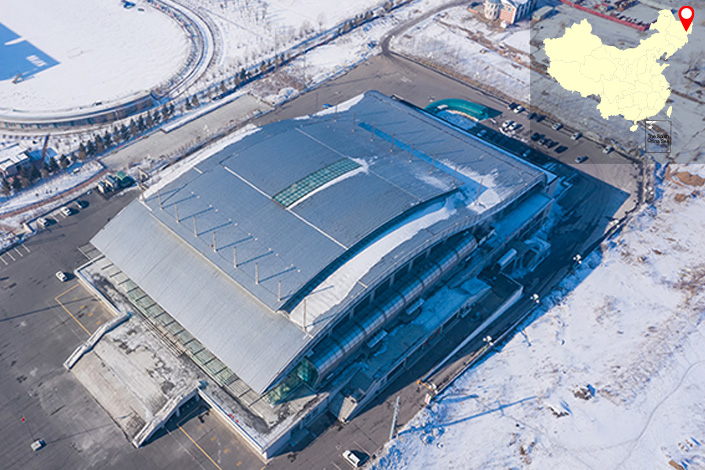

If we look closely, most members of Meng’s Qitaihe team came from poor families. Winter Olympic champions Wang Meng and Sun Linlin are from mining families, and Fan Kexin, who won a gold and a bronze medal at the Beijing Olympics, has cobblers for parents. The family of three used to live in a 6-square-meter corrugated iron house. And there was nothing smart about their outdoor training ground in Qitaihe either. Only in 2013 did the frozen border city get its first indoor ice rink.

The poor children who grew up with Meng to become world champions resemble the kids described in the famous French movie “The Chorus.” Their success deserves our admiration and praise, and it should be inspirational to the general public.

In a country where people admire elite education, Meng’s incredible achievements have gone largely unknown due to his simple biography, even though he trained many of our most revered winter Olympic champions.

As we near the close of the Beijing Winter Olympics, I would like to commemorate Meng, the true founder of the miracle of Chinese winter sports, and a tremendous grassroots harnesser of the Olympic spirit.

Wang Mingyuan is a researcher at the Beijing Municipal Commission of Development and Reform, and a scholar on the history of reform and opening up.

Contact editor Heather Mowbray (heathermowbray@caixin.com)

Get our weekly free Must-Read newsletter.