I came to China at the end of 2007, initially to cover the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the capital’s first Olympics and never expected then that I’d still be here for a second Games.

From 2008 to the present day, there have been many ups and many downs in China’s sports industry, and it’s been fascinating to watch. To sum it up in one line, it’s really about how the three strands of sports, business and politics are virtually inseparable when it comes to the Chinese sports industry — and that, I think, refers to China more than any other country.

There are two ways to view China’s Olympic legacy. The sporting legacy from 2008 was actually not that great. We saw a bit of a dip in the sports industry afterwards the Olympics and things didn’t really pick up for another five years or so when the government released a policy document at the end of 2014 which laid out its plan to develop the largest sports economy in the world. But 2009, for example, was down in the doldrums: the Olympics had packed up and left town, and there was no focus on sports. The political agenda had moved on.

The narrative about China announcing itself on the world stage in 2008 was very much true. In 2008, China was taking a seat at the top table. Now, China is setting the table, writing the place cards and telling everyone else where to sit. So, China holds a very different position on the world stage 14 years on.

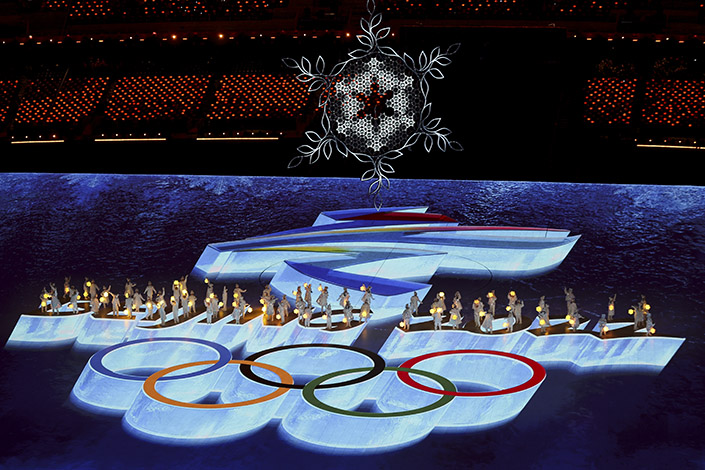

It was a cliche that it was China’s coming out party on the world stage, but it felt festive — very different to these Games for various reasons, not least Covid, where people aren’t really celebrating or even attending the Games. Firstly, these Olympics are not China’s first, so the novelty has worn off. Second, it’s the Winter Games, so by their very nature, it’s a smaller affair. Then, it’s more indoors — people aren’t celebrating in the streets and watching in outdoor bars like they were in 2008. Covid is a huge reason why we don’t have international spectators, which means that we don’t have a lot of international tourists dressed in their national colors walking around the street, so it doesn’t feel like an international sporting event. Beijing residents, with very few exceptions, haven’t been able to attend the Games either, so for all those reasons, it does feel more muted.

But the sporting legacy, interestingly, will be more significant from the 2022 Olympics than from 2008, because China’s winter sports is really developing, though it’s still at an early stage. Beijing said it aimed to have 300 million winter sports participants in the country and according to state media, there are already 346 million participants, but without a precise definition of what this means, it’s a largely meaningless number.

Let’s look at some actual facts: the way that skiing is counted globally is by ski visits. If one were to go skiing for a whole week that would count as 7 days, but it’s only one person. Last winter, China had 17 million ski visits. This winter the projection is 25 million. By 2025, the forecast is for 50 million ski visits per year. That would make China the single biggest skiing nation in the world, overtaking the U.S. That’s phenomenal growth and we’re really only at the beginning of that growth curve in terms of winter sports.

Involving the country

The traditional hub for China’s winter sports home has always been the northeast. Historically, the vast majority of China’s Winter Olympians have come from the northeast provinces, with many hailing from the city of Harbin.

But China has specifically tried to involve the whole country in the 2022 Games. They’ve done that by recruiting athletes from other sports — summer sports, such as track and field, rowing, trampolining, and even converted someone from martial arts into a ski cross athlete.

There’s a great story about an athlete called Chen Degen. He’s from Yunnan province in the southwest of China, where it’s pretty warm, tropical almost. He saw snow for the first time in 2019 when he came to Beijing and then they shipped him off to Norway for some training. Now, he’s one of China’s most promising cross-country skiing athletes, so that is one of the ways that they have embraced the whole nation.

In terms of bringing foreign coaches into China, China had more than 50 foreign coaches associated with Team China at these Olympics. That trend will certainly continue in the short term. In the longer term, China would like to have more Chinese coaches and there will be less of an emphasis, as we saw in ice hockey for example, on recruiting foreign-born players as well.

But that’s a gradual process. Chinese athletes need to get stronger in winter sports, but the Chinese coaches do too. Ultimately, they would prefer to have Chinese coaches, but they are still picking from the best in the world at the moment.

Eileen Gu front and center

Eileen Gu’s chosen to compete for China instead of the U.S. That’s just a dream as far as the Chinese government is concerned.

Commercially, she’s reportedly already making $35 million per year before she even won any Olympic golds. That number will rise, but she’s already fairly saturated in terms of commercial potential. That’s unusual. Most people have to win a gold medal or reach the top of their sport first. But she’s already managed to capitalize ahead of time.

There are so many different opinions about her even within China. I think there’s a split from the government narrative where she’s obviously a fantastic athlete and the face of the Games. But even now, I’m noticing some a little bit of conflict. Hu Xijin, the former editor-in-chief of the Global Times — and you always have to take his opinions with a grain of salt — made a really interesting point. He said that people should say that Gu is winning glory for Team China, not for the country. The reason he said that is because, further down the line, we don’t really know how this is going to pan out.

Gu is trying to play both sides right now, and the famous phrase that she’s been quoted as saying is, "When I’m in America, I’m American, and when I’m in China, I’m Chinese." Now that’s great for her. But if you’re a Chinese government official, you want her to be Chinese all the time. If she’s all in, representing China and saying “I’ve picked you,” you don’t really want her to be playing the American card.

Playing both sides makes sense for her, but it doesn’t necessarily make sense for the government. At the moment we have a marriage that works between the two sides. The Chinese government get to put her up there as the face of the Games and hope that she inspires a generation of people who will then help develop the winter sports industry. Once again, it’s combining the politics, the sports and the economics all together.

Gu right now has a huge commercial opportunity in the Chinese market. She’s earning more money from China than from her global sponsorships, but she is basically global celebrity at the moment. We don’t know how long her career is going to last. Athletes always have a narrow career window, and maybe she can flip it into just being general celebrity afterwards, but these are all unanswered questions. It’s working for her for now, but I’m not sure if it’s going to work forever.

Mark Dreyer is the author of “Sporting Superpower: An Insider’s View on China’s Quest to Be the Best.” This article was based on his interview with Caixin in a podcast program about Beijing’s 2022 Winter Olympics.

The views and opinions expressed in this opinion section are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial positions of Caixin Media.

If you would like to write an opinion for Caixin Global, please send your ideas or finished opinions to our email: opinionen@caixin.com

Get our weekly free Must-Read newsletter.