The killing of a gay man in Hagley Park

On the evening of January 23, 1964, a gay man named Charles Aberhart was cruising in the area inside and outside a public toilet near the Armagh Street entrance to Hagley Park in Christchurch. He was accosted by six adolescent boys aged between 15 and 17 who held and punched him, and one of whom robbed him. They left him dying beside the path. A passer-by discovered his body at about 10.30 that night. He knew and had seen who was responsible. By the following morning the police had identified and arrested the culprits and taken their statements.

There was no question of whether or not they had perpetrated the act. With one exception, they admitted it openly, pointed the finger at the main perpetrator (the one who refused to give a statement), and described it as a "queer bashing". They went on trial for manslaughter. The evidence took five days to hear and the judge, in summing up, reminded the jury that it was not necessary to specifically identify the actual person who struck the fatal blow, for the case to be proven. After a retirement of seven hours the all-male jury acquitted all six boys of any crime.

Who was Charles Aberhart? He was a draper from Blenheim aged about 36 at the time, who at one point in his career had been the manager of a branch of the Christchurch drapery store Millers, in his home town. The previous year he’d been convicted of indecent assault on another male and sentenced to three months in prison. The magistrate had said at the time that he was imposing a light sentence because the parties were consenting.

In 1964 Aberhart was in Christchurch visiting a friend in Sumner. He was probably in Christchurch because it wasn’t safe to pursue his sex life in Blenheim now that he had a conviction. I presume he’d gone to Hagley Park to see what he could pick up.

I was 18 at the time and a second year student at Canterbury University. I had been fully aware of my sexual attraction to other boys for about three years at that stage. Of course, there was no concept of ‘gayness’ around at that time, so I was still puzzling my way through the meaning of that insight about myself when these events occurred.

To say that the murder and the trial traumatised me was putting it mildly. I can still clearly recall passing a friend of mine on the old university site on the morning after the acquittal and him saying to me as we passed: “Looks like it’s open season on queers.”

My law student friend quite rightly perceived this as a shocking legal scandal. The perpetrators were plainly guilty, the judge had more or less told the jury to bring in a verdict accordingly, and the guilty parties had walked away free.

No-one was willing to say that homosexuals should have the same human rights as anybody else

The Christchurch Press reported it because it was a sensational local event. But most other newspapers didn’t even report the outcome, let alone the trial. That should not be a surprise. Forty years ago sexuality of any sort was a taboo subject for media attention or public comment, and homosexuality doubly so. The letters to the editor almost all supported the editorial deploring the verdict, but no-one was remotely interested in the fate of Aberhart. Instead, they debated the nature of juries and whether or not they were still appropriate to our legal system. No-one was willing to say that homosexuals should have the same human rights as anybody else.

An article in Landfall, by Ian Breward, and another by Vincent O’Sullivan in a now defunct but then quite significant journal of social and political comment, Comment, dealt with some aspects of the case. Breward was blunt: “Homosexuals in New Zealand labour under a triple disadvantage. They are regarded with disgust, suffer severe legal penalties if convicted, and worst of all, are not even guaranteed the posthumous satisfaction of seeing their assailants brought to justice; that is, they are not considered equal with other citizens before the law.” But his framework of reference is alien to us, informed as it is by the use of words such as ‘abnormal’ and ‘therapy’, and describing homosexuality as "not exactly a sickness but as something which should not be regarded as a crime."

Vincent O’Sullivan was more forthright. He describes the trial reports as often reading like a conspiracy against a dead man, and he expressed his difficulty in deciding whether the acquittal or the subsequent apathy was the more invidious. The whole trial, he thought, was infused with the notion that “the sexual proclivities of the victim should somehow alleviate the guilt of the accused, as if in some way the vice of one rubbed off as virtue on the other.” He was particularly outraged by the statement in summary of one of the defence lawyers who said: “Even if they went to Hagley Park to look for homosexuals there was no offence in this. The youths charged had probably learned a sound lesson. The case is a tragic one.” By which the lawyer meant a tragedy not for the victim but for the accused.

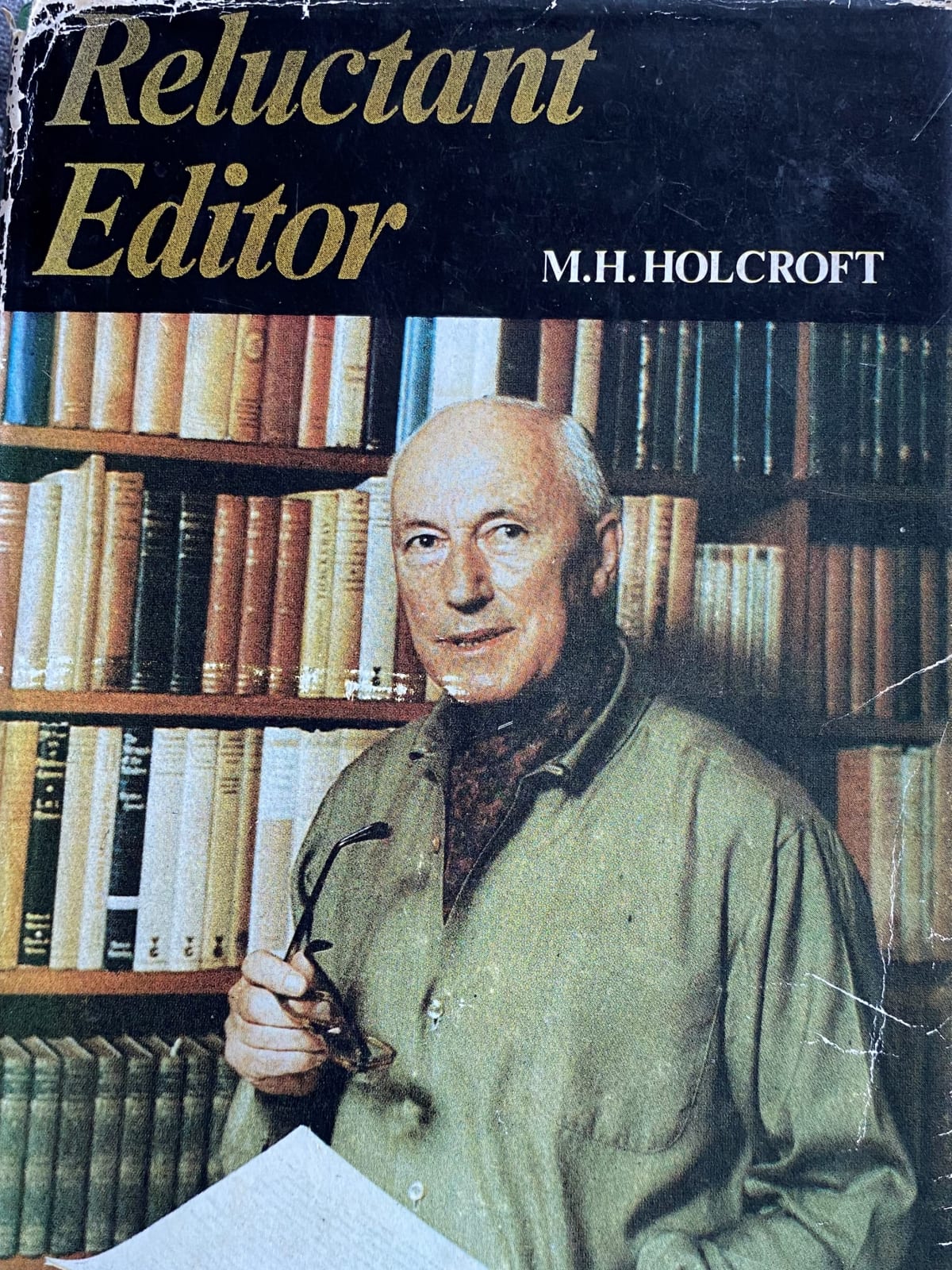

The only major periodical to comment was The Listener, which both editorialised and published letters on the case. Its editor, Monte Holcroft, was noted for his humanist and liberal views which he often expressed editorially. The editorial he wrote on the Aberhart case was in fact considered to be the epitome of his style to the extent that it was chosen for reproduction at the time of his death in 1993 as a tribute to him. What he had done was considered brave by the standards of the time.

But in retrospect Holcroft’s editorial seems rather odd. Like the Press leader and letters, Holcroft was not particularly concerned about the fate of Aberhart per se (he doesn’t actually mention him by name). He even makes a gesture towards those who favoured the acquittal, remarking: “Some indeed might believe that it was better for all the accused to go free than to risk unjust punishment for one or two who were only technically guilty.” You’re either guilty or you’re not. So that’s a curious remark for a start.

Beyond that his editorial is notable for two other reasons. The first is Holcroft’s specific statement that Aberhart deserved compassion not because his human rights had been infringed, or even because he was dead, but because he was sick. In 1964 of course, it was to be a further decade before the American Psychological Association removed homosexuality from its list of pathologies; the WHO didn’t do so until 1992. In 1964, to describe a homosexual as sick rather than morally evil was actually a rather daring or even radical thing to do publicly.

But beyond that, although prepared to say that Aberhart was therefore no more deserving of death than any other person, the importance of the case, said Holcroft, lay in what it could tell us about the narrowly masculine outlook of our society and the segregation of the sexes it entailed. To him, Aberhart was simply a peg on which to hang some critical things he wanted to say about the sort of place New Zealand was and which he and his fellow liberals deplored. In retrospect, therefore, Holcroft’s views seem not so much brave, humane and liberal, as quaint and patronising.

*

I was perfectly well aware even at the age of 18 not only that there were homosexual men among us, but that they were not universally abhorred. In fact they were tolerated and even welcome in some social situations. When I went to adult social gatherings in those days in the homes of my school friends it would not be unusual for there to be openly gay men present. We’re not talking about the liberal middle classes here by the way; this was suburban working class Christchurch where you might perhaps least expect such a thing. Sure, the other males present treated them in a fairly offhand manner. But overt hostility towards them was rare, and was actually rather frowned upon, although they sometimes had to put up with being the butt of contemptuous or even offensive jokes and jibes as the price of their inclusion.

They were acceptable because they were usually present as escorts to single women who didn’t want to go to parties on their own. If women did come alone to parties in those days they were automatically assumed by all single males present to want sex, and to be available to anyone who approached them so they took someone with them to the party as protection. Gay men were ideal for that purpose.

Women were not allowed to go into public bars in pubs until 1967, because it was assumed that if they did, they must be a prostitute looking for customers. However they could enter a private bar for a drink if they were accompanied by a male escort who purchased the liquor. These bars – popularly known as ‘cats’ bars’ – were identifiable by a sign over their entrance which said: “Ladies and escorts only.” Gay men played a significant role in the 1960s for women who wanted to go out for a drink on Saturday afternoons but had no husband or boyfriend to go with them, because they could act as escorts, and they often went on to parties together afterwards.

Beyond that, of course, there were recognised cruising grounds in most major towns. These were relatively well-known to quite a lot of the population at large. I can recall my own parents expressing some concern about me riding my bike through Hagley Park at night on my way home from late lectures although they were rather vague about what it was that was endangering me because of the general taboo on specifically mentioning the subject of homosexuality. I think I got the idea nevertheless. More to the point the young gay bashers on that January night in 1964 knew exactly where to go to find their ‘queers’. The brick dunny by Little Victoria Lake in Hagley Park was Christchurch’s most notorious cruising ground. It seems to have been quite active on the night in question, because the court heard some other eyewitness evidence from people who had also been present. They were fairly vague about what they were doing there, and nobody pressed them on the matter, but it seems pretty clear that they were cruising.

"The bleating of the lamb excites the tiger", as Kipling observed

The young perpetrators of Aberhart’s murder were sufficiently au fait with how they thought things were done to send one of their number, selected as ‘bait’ they said, because he was the youngest looking, into the toilet to see what was happening. And before they got to Aberhart they had already confronted several others. They got short shrift however. One of the men they approached produced a large pair of scissors and warned his would be attackers off. Two others made common cause and walked away together for mutual protection. It was only when they cornered Aberhart that our young gay bashers found their victim.

He tried to escape but they bullied him back into the park. He appealed to a passer-by to "get the police" but the person in question – who later gave evidence – once he saw what was going on refused to intervene. So Aberhart offered his tormentors money for coffee or fish and chips. Regrettably, as Rudyard Kipling once pointed out “the bleating of the lamb excites the tiger.” Because it was at that point that the attackers pinioned him and punched him. The forensic pathologist’s evidence makes horrific reading. There were a number of blows to Aberhart both as he stood helpless and after he fell to the ground. The one that most likely killed him was a blow to the face with caused a haemorrhage of the brain. At least two of the boys had already walked away, refusing as they later said to have anything further to do with what had started out as what they saw as a bit of a lark but which had obviously got completely out of hand. The others fled, although one who claimed he went back to see if the victim was all right, was sufficiently self-possessed to use the opportunity to steal Aberhart’s money.

*

The point about understanding the six perpetrators of Aberhart’s murder, from the brief biographical descriptions contained in their statements to the police, is how utterly ordinary they were.

All had obviously left school as soon as they could at 15. Two were in apprenticeships but the others were in dead-end jobs. They grew up in the same featureless postwar Christchurch suburbs as I did. Their activities on the early summer evening prior to the killing were aimless. They watched a little bit of television, helped a neighbour start his car, had a cup of tea with a friend’s mother, and eventually met up with one another and went off ‘to bash a queer’ for want of anything better to do. They were like hundreds of adolescent boys in Christchurch at that time.

Time and place no doubt played their part. In her astonishing tour de force analysing the Christchurch crèche affair Lynley Hood has one of the best characterisations of Christchurch I have ever encountered. She describes what she calls its fake gentility and belief in the innate superiority of its self-appointed elite before going on to remark: “This snobbery, imposed from above, seems to have provoked in those below a defiant eccentricity. Throughout its history Christchurch has been as renowned for its cranks and its zealots, as it has been for its Englishness and its class distinctions.” It was no surprise to her that the exiled German philosopher Karl Popper, during his unhappy eight years there in refuge from the Nazis wrote The Open Society and Its Enemies. But she goes on to caution that this is not funny, and reminds us that Christchurch is the setting for some of New Zealand’s most bizarre crimes. In that context she notes in particular the acquittal of Aberhart’s assailants. The implication is that this could only have happened in Christchurch.

Those who admire Christchurch as "the most English city outside England" or, conversely, its detractors such as the gay poet D’Arcy Cresswell who once described it as "like a broken down cow town in the American midwest", miss the point. Christchurch is no different to the rest of New Zealand, only more so.

There are two important things to recall about our society which are thrown into relief by the Aberhart case. The first is how violent we are and how that violence defines our character, and particularly its masculinity. Despite my strictures, Holcroft may have been on to something after all. The social violence which led to Aberhart’s death is still with us and its levels have always been unacceptably high. Furthermore, those levels have often gone unrecorded. In the New Zealand of the fifties and sixties in which I grew up, family violence towards women and children was perfectly acceptable. That this attitude is also still with us is indicated by the [current] bitter opposition to the repeal of s59 of the Crimes Act which currently allows the use of ‘reasonable force’ by parents against children.

But beyond that again, we are dealing with a pathology. Forty years ago people would have said that it was the homosexuals who were suffering from a pathological condition. Now, in a spectacular reversal, we have come to regard homophobia itself as the pathology. I would go further and say that homophobia is actually a symptom of a broader pathology which encompasses authoritarian attitudes towards crime, extreme evangelical religious views, strict hierarchical views of family life, including opposition to civil unions, racist views concerning bi- and multi-culturalism, and a host of other symptoms which together constitute what an earlier generation of social psychologists called the authoritarian personality.

That sort of person is no longer as dominant in our society as they used to be but they still make up a sizeable group. More worryingly, we do not lack for politicians unscrupulous enough to mobilise it for their own ends. What the death of Charles Aberhart reminds us is that we need to beware. His murderers, as well as physically, in spirit still dwell among us.

Taken with kind permission from the newly published essay collection The Scone in New Zealand Literature and Other Essays 1990-2020 by Tony Simpson, available in selected Wellington bookstores or by contacting the author on sugarbags@xtra.co.nz.