Few Ontario residents know how land use planning regulation shapes their physical environment, including where new housing is built, the size and type of buildings, and housing density. As a result, most people are only interested in the topic when a new housing project is proposed near their homes.

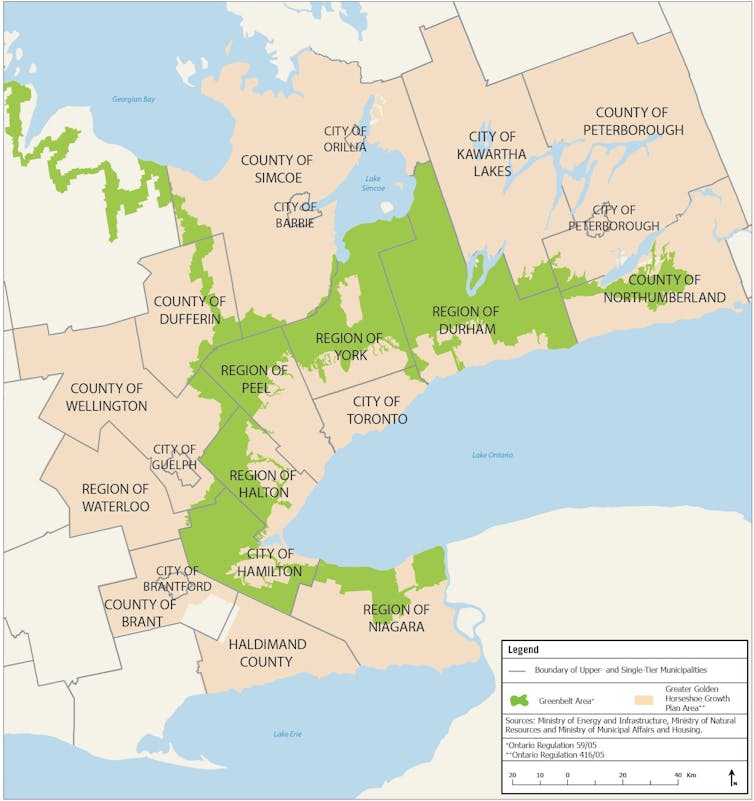

In reality, planning regulation has far-reaching influence on our lives, and especially on the housing crisis. It’s a primary reason for the high housing prices and rents in the Greater Golden Horseshoe — a massive region that is centred on Toronto and spans Southern Ontario.

Because of this, land use planning impacts certain parts of the population more than others, including the middle class, first-time house buyers, renters, immigrants and lower-income residents.

Although few pay attention to it, the development, regulation and impact of land use planning has more to do with the average person than they realize. A sweeping reform could reduce housing and rent prices, at no cost to the public purse.

The Growth Plan

The planning system is often criticized as time-consuming, overly bureaucratic, uncertain and costly. In Ontario, land use planning is carried out by municipalities and shaped by provincial legislation.

But the Greater Golden Horseshoe has had an additional layer of bureaucracy in the form of a provincial planning policy called the Growth Plan. This policy places restrictions on what parts of southern Ontario can be used for development and infrastructure via the Planning Act

The Growth Plan became law in 2006 under Dalton McGuinty’s Liberal government. Since then, it has been adapted by successive Ontario governments, most recently Doug Ford’s Conservative government.

The Growth Plan represents an ambitious effort to shape how residents live, work and interact with one another with land use regulations. Ensuring a sufficient housing supply to improve affordability is just one of many objectives the Growth Plan is intended to address.

Research shows more restrictive planning regimes result in higher housing prices. A 2017 study found that land use regulation in Auckland, New Zealand, could be responsible for up to 56 per cent of an average house’s cost.

Another study from California found that housing prices could decline by about 25 per cent in Los Angeles if its planning regulations were decreased to the levels similar in the least-regulated cities in California. Based on my own estimates, home prices in the Greater Golden Horseshoe could fall by a similar amount under a benign land use regulatory system.

Supply and demand disparity

While affordable housing is a stated goal of the Growth Plan, the interpretation and implementation of its policies will reduce housing affordability, not improve it. According to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Ontario needs to build 1.8 million new homes by 2030 to get housing affordability back to where it was in the early 2000s.

While most Greater Golden Horseshoe homebuyers undoubtedly prefer ground-level homes, the Growth Plan prioritizes higher-density forms of accommodation, instead of single-detached houses.

This disparity between housing demand and supply sets the stage for housing prices to increase even more in the coming years. The four regional municipalities, Durham, York, Peel and Halton, around Toronto all face a marked disparity over the coming three decades between housing planned and the market.

The supply of single-detached and semi-detached houses will only be 25 per cent of the new housing, compared to a demand of 50 per cent.

The reverse holds for apartments: 50 per cent of the new housing will be apartments, while the market demand is just 25 per cent. The demand and supply of townhouses will be similar, at 25 per cent of the new housing.

The sizeable shift from single-detached houses to apartments over the next 30 years is expected to happen under the current provincial government’s version of the Growth Plan passed in 2020. In the earlier version of the Growth Plan passed by the last Liberal government in 2017, even fewer ground-related homes would have been built in the future, resulting in even more stress on affordability.

Countering adverse price impacts

To counter the adverse price impacts of the Growth Plan, I have two proposals for the provincial government. First, municipalities must offset any planned reduction of single-detached and semi-detached houses below market demand with an equivalent number of “missing middle” housing.

Missing middle housing includes townhouses and low-rise apartments with four storeys or fewer, like stacked townhouses, and are the closest substitutes for single-detached houses. These should be added in existing urban areas (mainly single-detached neighbourhoods) and on vacant fringe lands.

Second, the government should conduct an in-depth review of the land use planning regime to improve efficacy and minimize adverse impacts on housing affordability, as was undertaken in New Zealand.

What is needed is a sweeping overhaul to increase not only the numbers of new housing units built, but to accelerate approvals of all housing types, with particular attention paid to single-detached and missing middle housing.

Without these changes, housing costs will continue to rise and many households will face longer commutes as they move farther away from employment centres in search of less expensive single-detached houses and townhouses.

Frank Clayton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.