With Ontarians heading to the polls on June 2, Premier Doug Ford government’s advertising campaigns are ramping up.

The government’s environmental credentials, notably its recent investments in “greening” the steel sector and in electric vehicle manufacturing, have figured prominently in its messages.

This focus comes as something of a surprise to those familiar with the Ford government’s record on environmental issues, which has moved the province’s approach to environmental problems backwards by half a century or more.

The major features of the Ford government’s performance on the environment are well known.

It has:

Dismantled the previous government’s relatively comprehensive climate change strategy immediately following the June 2018 election.

Lost a battle on carbon pricing with the federal government before the Supreme Court of Canada.

Cancelled more than 700 renewable energy projects at a cost of hundreds of millions of dollars and terminated the province’s largely successful strategy on energy efficiency.

Rewritten the planning rules at provincial and local levels to favour developers.

Aggressively pushed for proposals for sprawl-inducing highways through the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA) Greenbelt and tried to open parts of the greenbelt to developers.

Undermined the authority of conservation authorities with respect to areas prone to flooding.

Weakened protections for endangered species, particularly with respect to resource development.

Repealed the province’s toxics use reduction legislation.

Dismantled the province’s regulatory framework for controlling industrial water pollution.

Folded the province’s previously independent environmental commissioner into the office of the auditor general.

Dismantled environmental assessment process

This agenda has continued, and in many ways accelerated, under the cover of “pandemic recovery.”

The province’s environmental assessment process, first established in 1975, was largely dismantled. Broad powers have been given to provincial agencies, most notably the provincial transit agency Metrolinx to build what are often poorly conceived and politically motivated transit projects. The province’s most recent moves have sought to marginalize the roles of local governments in planning matters and to eliminate public consultation requirements as “red tape.”

Read more: Doug Ford is clear-cutting Ontario's environmental laws

The province did release a Made in Ontario Plan for the Environment in 2018 and updated it this spring. But it has done virtually nothing to implement the plan. The Ontario auditor general concluded that even if the plan were implemented, the province would fall short of its stated targets.

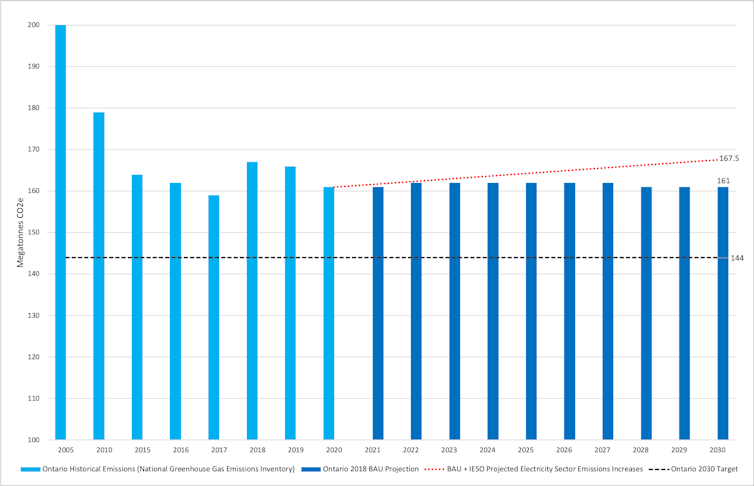

The province’s greenhouse gas emissions have been relatively stable following a big drop with the 2013 phase-out of coal-fired electricity. But it is now on track to see major increases in emissions, particularly from the electricity sector, a development that is not accounted for in the province’s plan.

In the process, the province has moved away from rules and evidence-based decision-making to approaches based on access, connections and political whim. The resulting governance model is one more rooted in the political norms of the 19th century than the 21st. The big winners so far have been clear: developers; the mining and aggregate industries; and nuclear and natural gas based incumbents in the energy sector

The province’s new interest in greening the steel sector and electric vehicle manufacturing suggests an awakening. But these developments don’t flow from a concern for the environment. Rather they reflect a recognition, at some level, that global economic shifts in the direction of decarbonization are taking place and that Ontario risks loosing what remains of its manufacturing sector if it doesn’t respond.

So far, these developments have been sporadic and reactive. In sectors like mining and hydrogen, the government’s new strategies have relied far too much on the input of industry lobbyists, too little on serious thought or analysis.

In the case of the critical minerals strategy, the implications for Indigenous Peoples and their rights have been ignored. There is no movement in key areas like renewable energy and certainly no wider vision for Ontario’s role in a low-carbon global economic transition.

Increasingly authoritarian

For the most part, the Ford government seems to have operated on an assumption that anyone concerned about climate change and the environment wouldn’t be voting for it anyway. The moves to green some sectors may reflect a realization that the political landscape may not be that simple. Even some Progressive Conservative Party voters may sensitive to the implications of a changing climate.

Barring a climate-related extreme weather event or a disaster on the scale of Walkerton during the campaign period, the largest environmental political risk facing the government may be the growing backlash against the government’s increasingly authoritarian approach to planning and development issues.

The ongoing threats to the GTHA Greenbelt and, most recently, the aggressive use of ministerial zoning orders in Richmond Hill and Markham to support hyper-intensive development that only seem to serve the interests of the development industry are causing unrest among municipal governments and residents in the crucial 905 region around Toronto. That region forms a core part of the base of the Ford Nation constituency.

The alternatives

For Ontarians looking for alternatives to the current government around climate change and environmental issues, the province’s Green Party has, perhaps unsurprisingly, provided the most comprehensive response so far. But the party’s polling has not been strong, likely collateral damage from the federal party’s meltdown in the 2021 federal election.

Read more: Scrapping environmental watchdog is like shooting the messenger

But the potential role of the Greens, whose deputy leader is the province’s former environmental commissioner, in the Ontario election should not be underestimated. In highly fractured vote the Greens could end up holding balance of power in a minority legislature, as happened in British Columbia in 2017.

The environmental dimensions of the NDP’s platform are disappointingly thin on content and details by comparison. The party does propose a net-zero plan for 2050, to reintroduce a cap and trade system for greenhouse gas emissions and to re-engage around renewable energy development. The Liberals have said little specific to environmental issues so far.

The 2022 election looms as the most important for Ontario’s environment in modern era, and its impact may echo for generations to come.

Mark Winfield receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.