Amidst the desolate hilly terrain between Jivti taluk of Chandrapur district in Maharashtra and Kerameri mandal in Kumuram Bheem Asifabad district in Telangana, are 14 villages in the Parandoli and Anthapur gram panchayats. Here, 3,023 residents, of a population of about 5,000, enjoy the power of voting in both Maharashtra and Telangana.

Both gram panchayats are dependent on the Maharashtra and Telangana governments and the residents participate in almost all elections on both sides, says Laxman Kamble, the first sarpanch of Parandoli, elected in 1995.

With polling to the Telangana Assembly to be held on November 30, these villages, predominantly occupied by Marathi-speaking Scheduled Caste (SC) communities, will exercise their voting rights owing to an unresolved boundary dispute. The population also includes some Lambada tribespeople and Muslims who had migrated from drought-hit Nanded, Parbhani, Latur, and Jalna districts of Marathwada between 1970 and 1971 in search of a livelihood. Contesting candidates are actively campaigning in these hilly areas, recognising the significance of the villages in the electoral landscape.

“We vote in both States’ elections, but several of our problems, including road connectivity, healthcare and higher education for children remain unresolved,” says Pundalik Waghmare, a Dalit farmer from Parandoli. The villages lack motorable roads, posing a significant challenge in terms of accessibility.

Double benefit

Half the villages – Parandoli, Mukadamguda, Maharajguda, Lendijada, Kota, Shankerlodi, and Parandoli Tanda – are part of Parandoli gram panchayat. The remaining – Bolapatar, Isapur, Anthapur, Indranagar, Lendiguda, Gowri, and the newly added Narayanguda – are part of Anthapur gram panchayat.

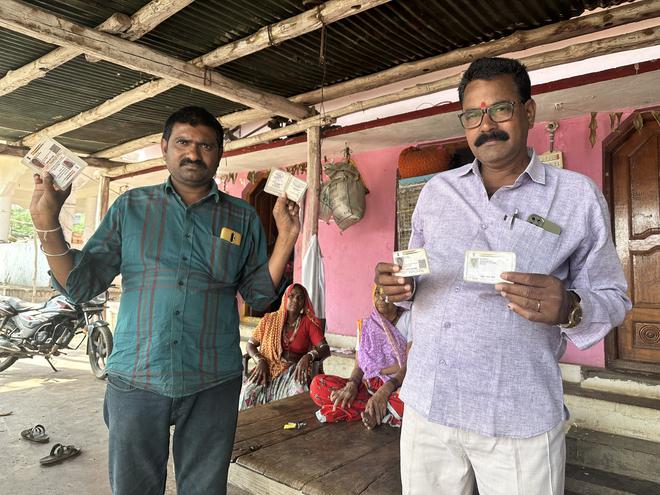

People in this area draw benefits of social welfare schemes from both States. “We have two voter cards, two Aadhaar cards, and get rations and pensions from both the State governments. KCR [Telangana Chief Minister K. Chandrashekhar Rao] also gives us the Kalyana Lakshmi scheme [financial assistance to the bride’s family], but neither of them gives us pattas [title deeds] for our lands we have been cultivating for decades,” said Subhabai Mallahari Waghmare, 60, from Parandoli.

These villages have two Anganwadi centres, two primary healthcare centres, two water tanks, and two schools (Marathi- and Telugu-medium) run by the two State governments. In a country where jobs are sparse, people have two MGNREGA job cards. Each village even has two sarpanches. In these rural areas, walls serve as billboards for welfare schemes implemented, in both States in Marathi and Telugu.

The voters themselves have always been in favour of voting in the two constituencies. “We are not worried about ‘one nation, one election’ and don’t want to give up our dual voting right, as that could curtail our double benefits without any legal solution,” a villager said.

A history of separation

The issue dates back to the unresolved tensions arising during the linguistic-based reorganisation of States in 1956. This dispute led to inter-State tension, more so when the Andhra Pradesh government set up polling stations in these villages for the first time during the 1989 election. (Telangana was carved out of Andhra Pradesh on June 2, 2014).

It was further escalated in 1999 when the Andhra Pradesh High Court ruled that the villages be part of the Telugu State. Maharashtra contested this decision in the Supreme Court, leading to a debate about dual voting, though the matter remained unresolved as elections were held separately in Chandrapur (in Maharashtra) and the united Adilabad district (in undivided A.P.) in 2004.

That year, when the Election Commission mandated that voters choose a single constituency, Mr. Kamble recalled the impact: women voted in the Chandrapur constituency while men voted in Adilabad. “But now, we don’t have that problem. We vote in both elections and leaders from Maharashtra and Telangana come and campaign here. We get to choose representatives from both States,” said Waman Pawar of Maharajguda.

Attracted by the Telangana government’s welfare schemes, including free power supply to farmers; Rythu Bandhu and Rythu Bima, both for farmers; and Dalit Bandhu, the residents of these villages have been demanding they merge with Telangana hoping they would get pattas for their lands. “We are getting more benefits from the schemes of the KCR government compared to Maharashtra,” Mr. Pawar, who belongs to the Lambada tribe, said.

The Election Commission will be setting up four polling stations in the disputed villages for the forthcoming Assembly election. Telangana Chief Electoral Officer Vikas Raj, said, “After the delimitation process in 2006, these villages were included in the 005-Asifabad constituency. In 2004, recognising the territorial dispute, the Election Commission of India issued instructions to the CEOs of Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra to take measures to avoid double voting. The CEO of Telangana reiterated these instructions for the 2019 Parliament elections.”